Lumbering to Extinction in the Digital Field: The Taylorist Office Building

The global dominance of North American tall and low office building typologies throughout the 20th century was nearly total. Skylines worldwide and the physical and social structure of most suburbs are testimonies to this enormous technological, economic, social, cultural, and, of course, architectural achievement. Even the Roman Empire failed to achieve such hegemony.

There are many reasons for this. Two deserve particular attention from architects. The first is the extraordinary daring of architects in Chicago (and a little later in New York) in bringing together multiple technologies to create the high rise office building—in the context, of course, of an extraordinary explosion in economic activity in the U.S. in the last three decades of the 19th century—and the parallel and equally unprecedented inventiveness in real estate, engineering, and construction practice. Second is the specific intellectual debt the world owes to Frederick Taylor’s concept of “Scientific Management,” i.e., the rational-ization of the processes of production to achieve greater efficiency not least in the design and construction of office buildings and subsequently in the management of the burgeoning administrative activities within them.

Will the universal success of what I have elsewhere called the “Taylorist” office ever be checked? It would seem so. The enormous increase in the power of Information Technology is well on the way to super-seding the purely industrial logic that generated the North American office building. At least one alternative office typology, the essentially anti-Taylorist, “Social Democratic” office, democratically designed with input from Workers’ Councils specifically to respect and defend the rights of each individual office worker, has flourished in the very special (and almost certainly temporary) political and economic environment of post-fascist Northern Europe. Yet another architectural and urbanistic phenomenon, the “Networked Office,” which exploits information technology to create unprecedently free relationships between the physical and the virtual realms is now emerging, and it does not depend on Taylor’s temporal and spatial logic.

New ways of working made possible by ubiquitous, powerful, reliable information technology should create new office architecture and new city forms. There is now less need for individual desk-centered space and more need for widely distributed spaces of formal and informal gathering. People can now do their solitary work anywhere and anytime, yet they still need face-to-face interactions.

Electronic connectivity has changed our world. It is no longer useful to rely on temporal categories such as the five-day week and the eight-hour day to place boundaries on office work or measure the environmental performance of buildings. Boundaries between what is work and what is not are shifting fast. Work is spilling into ever wider and more complex spatial and temporal landscapes. The consequence for architects and for everyone else involved is that the office building no longer has a monopoly on accommodating work, and thus, from both a managerial and an environmental point of view, has become a misleading and obsolescent unit of analysis.

Indeed we should ask ourselves why empowered and self-reliant people, equipped with increasingly powerful information technology, should come to office buildings at all. The map of the spatial configuration of many contemporary businesses is already a global network of interactions, some face-to-face and many virtual. Core physical space is diminishing while interactions that spill beyond and between the walls of office buildings are multiplying.

And yet, paradoxically, cities not only persist but are becoming bigger, busier, and more crowded. City life is also increasingly networked more locally and intensely. Virtuality is complementary to physicality. The most successful and congenial cities have the greatest density of overlapping social networks, some physical, others electronic. It is parallel leakage between these networks that creates serendipity, Horace Walpole’s 18th-century neologism for taking advantage of unplanned but not totally unexpected social and business encounters. Of course, Walpole knew the value of serendipity well because he lived in highly permeable, social, densely networked 18th-century London.

A Historical Perspective

In the long historical view, the office has been neither a particularly venerable nor a particularly stable building type. This thought has been brought into sharp focus recently by my experience of working for the Somerset House Trust, the body responsible for managing what is often claimed to be the oldest office building in London, the first phases of which were constructed between 1776 and 1801, and the last phase of which, the West Wing, was completed in 1852. Each stage in the creation of this magnificent palazzo complex overlooking the Thames exemplifies a small but significant development in the office as a building type. The Eastern Wing originally consisted of five separate “houses,” each intended for a specific government department, each with its own front door and main staircase—with living accommodations above. The West Wing, facing the original Eastern Wing across the great central court, retains five separate, houselike, external doors, presumably for reasons of symmetry. However, this wing is much more integrated internally by a continuous, central corridor linking every room on each floor. The New Wing, in addition to having continuous internal corridors, displays what may have been a startling innovation—a single front door. This sequence shows architectural design emerging from aristocratic patronage and heading toward departmental autonomy of an increasingly centrally controlled and managed bureaucracy.

Let us go back a little further. To the east of Somerset House is a large, semi- enclosed area that exemplifies an even earlier office type: the college-like Inns of Court, with many front doors, chambers for both living and working, libraries, great halls for dining, as well as a church, masters’ houses, gardens, and courts. The Inns of Court are not usually recognized as office accommodation, although to this day they remain the main professional base for the educational, business, and social activities of barristers. In the context of the social geography of London, Westminster is where the King and Parliament dwell, and the City of London is where the banks and the money are. It should be no surprise that the Inns of Court are equidistant from power and money. The Inns have a special relevance in our information-technology-based, knowledge economy because they demonstrate: how important a role the physical environment plays in stimulating interaction; that multiple uses can be closely juxtaposed; how pleasantly habitable a high density, mixed used, knowledge-based urban fabric can be; and how well incremental adaptation and change are built into such a fabric.

My conclusion from the evidence of this tiny fragment of London is that the earlier one goes back into the history of the office, the more peripatetic people appear to have been, the more diverse their access to work-places, and the more permeable the urban context within which they worked. Even without information technology, people knew how to move about, choose appropriate settings and share space. Nineteenth century intellectuals —Darwin, Huxley, and Thackeray—had their clubs; 18th-century writers—Addison, Steele, Dr. Johnson, Goldsmith, and Boswell—discoursed in inns and coffee houses; a 17th-century civil servant, Samuel Pepys, was both a home worker (his private office was next door to his house) and energetically peripatetic between multiple places of work. Not just one building, but all of London was these men’s office. When architect Charles Cockerell’s bureaucratically minded client elected to put a single front door on the New Wing of Somerset House, thousands of other doors slammed shut.

I conducted an exercise in 2007 with a class of Masters students from the Design School at Kingston University. Part of my intention was to help the students —most from abroad—get to know and understand London, since they were unfamiliar with the functions, textures, and meanings of its parts. From my perspective, the more important part of the exercise was to compare the utility, value, and meaning of contrasting urban forms. The students were asked to explore and report their impressions of Canary Wharf and Soho, two similarly sized chunks of London’s urban fabric, each very different in physical character and patterns of use. Canary Wharf and Soho are both economically vigorous, having attracted very different sectors in very different ways. Canary Wharf accommodates very large banks and closely connected financial service organizations, including some of the biggest law and accountancy practices. Soho has been successful in attracting the film industry in a wide range of post-production houses, as well as fashion businesses, tourism, and many forms of entertainment.

Soho’s fabric is that of a low rise but still relatively dense 18th-century domestic mesh of narrow streets and squares overlaid by many 19th- and 20th- century interventions and additions, including retail, warehouse, and semi-industrial spaces, many of which have been extensively converted to accommodate post- industrial uses. Canary Wharf, unlike Soho, has been created almost instantaneously within the last two decades on a narrow strip of land between two redundant docks. It is new, largely mono-functional and dramatically cut off from the surrounding area. In urban terms, the Wharf’s model is not unlike the downtown of a moderately successful, mid-sized North American city.

I asked the students to decide which of these two very different models of urban fabric would stand a better chance of remaining in beneficial use in the year 2030, keeping in mind Richard Sennett’s criterion of not being “brittle”1 (which I will describe more fully below). The images selected by the students to illustrate their comparisons included, in the case of Soho, one astonishingly populated restaurant map of the area—there can be no better image of controlled permeability than a thousand highly varied and infinitely welcoming restaurant and café doors. In contrast, many of the images used by the students to describe Canary Wharf emphasized techniques of exclusion—by guards, gates, cameras, and cops. From the students’ perspective, the high levels of security characteristic of Canary Wharf prevented permeability. Stringent security may be inevitable in post-9/11 cities. Nevertheless, Canary Wharf’s manifestations of security were not easy for my students to condone—overt, controlling, spilling out into the streets, contaminating the public realm.

To look to the future, look earlier in the past. And look to Soho.

Sustainability, Information Technology, and the Supply Chain

My recent book Work and the City is one in a series of books about sustainable design.2 I was stimulated to write it partly by the realization that the biggest opportunity in achieving sustainable office space was not for architects to specify more environmentally efficient facades but to think twice about designing and building any new office buildings given the great potential for intensifying space use in the notoriously underused stock of existing office space. This thrifty policy fits neatly with William Mitchell’s argument that the conventions that shaped the workplaces of the Industrial Revolution—working in the same place and at the same time—are now obsolescent.3

Conventional Taylorist office buildings, both high and low rise, are not sustainable. They are under-occupied and under-used, unsuitable for emerging ways of working and difficult to convert to new uses. They sterilize opportunities for embryonic enterprises and fail to accommodate inter-company transactions, mobile work, or overlapping activities. The more office work changes, the more limited the familiar typologies of office buildings become.

Today, in contrast, information technology has the potential, if used intelligently, to enfranchise people to use time and space in more fluid and environmentally efficient ways. However, to achieve these new dimensions of environmental efficiency and personal freedom, new temporal and spatial conventions will have to be invented, and this poses many challenges for clients and architects.

Sociologist Richard Sennett has accused the Modern Movement in architecture and urban design of three fortunate addictions:

→ to the large scale;

→ to over-determined, over prescriptive building forms. Sennett uses the term brittle to describe the consequent fragility and vulnerability of mono-functional buildings, especially office buildings, many of which are unlikely to accommodate change even for different kinds of office activities, let alone other functions such as residences or retail;

→ to centripetal patterns of urban development, the planners of which concentrate on “centers” and neglect interstitial and peripheral spaces.4

The formula for reversing the problems Sennett sees in the 20th-century city suggests that architects and urbanists design places that make possible:

→ closer adjacencies between buildings of different scales to make sure that spaces for small groups can be accommodated close to or even above, under, or within structures for large groups;

→ multifunctionality through the planned juxtaposition of complementary and mutually supportive uses within a varied regime of rental levels and forms of tenure. More short term, relatively cheap accommodation suitable for smaller creative businesses within fashion, media, and design, spaces like rough and ready lofts, in which concepts can be conceived, developed, and produced adjacent to the larger, more stable businesses that can implement ideas but that need instant and ongoing access to creativity;

→ the provision and maintenance of many and diverse attractive interstitial places, permeable in various degrees, designed to make possible the maximum number of serendipitous encounters between businesses and enterprises of many different kinds, sizes, and cultures.

Does Form Need to Mimic Process? A Look at _Corporate Fields_

Against this background I read Corporate Fields, a beautifully illustrated account of three years of investigation into the future of the office carried out between 1999 and 2002 in the design Research Laboratory of the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London.5

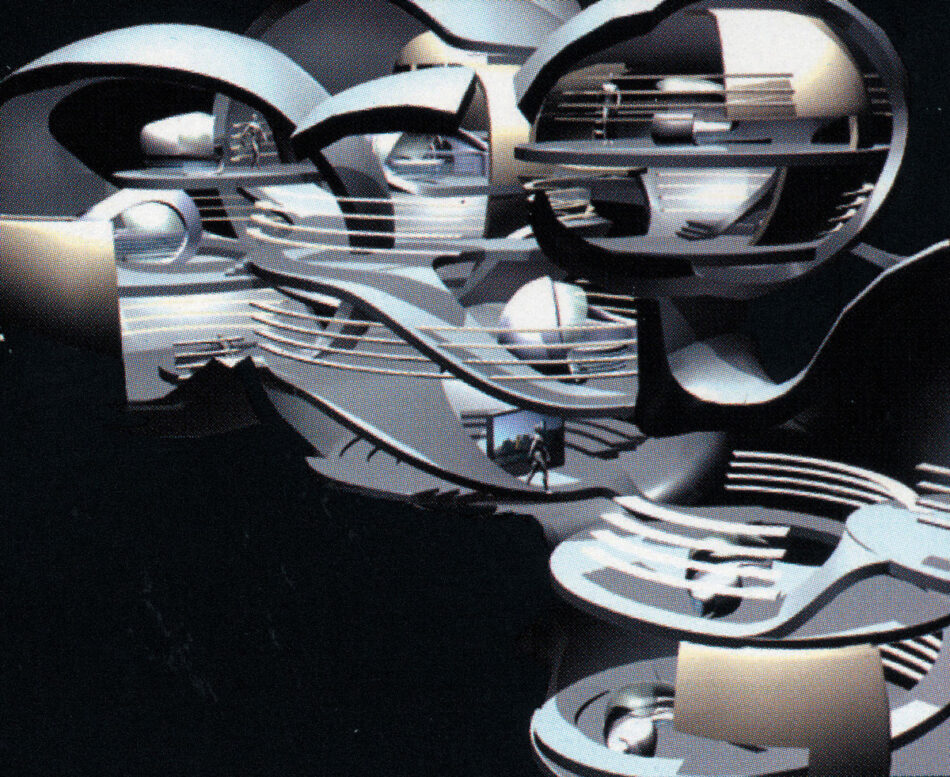

The most important enabler behind the “Corporate Fields” endeavor was computational design—the digital generation and exploration of unprecedented architectural forms producing continuities, fluidity, warping, and folding. But the implications of the book for office design go deeper.

The arguments made by Brett Steele, Mohsen Mostafavi, and Patrik Schumacher, three of the principal authors and the leaders of the design studios that generated Corporate Fields, might be reduced to the following propositions, strikingly similar to my own:

Urban issues Internal office functions are likely to be intermingled with other complementary functional programs and thus construct a larger indoor urban territory. The appropriate scale of the office building will be somewhere between a large building and a fragment of the city.

The shape of external membranes for such buildings will be more influenced by internal “corporate fields,” fluid and open ended patterns of interaction, than by external constraints.

Architectural issues Continuous, folding, complex architectural forms are not only a metaphor for the increasing complexity and interactive nature of the knowledge economy but also shapes that create physical conditions that are both appropriate to and facilitative of increasing organizational complexity and interaction.

Office buildings for the knowledge economy will be interconnected in section and will no longer need to be constrained by having to provide repetitive, standardized floor plates.

Design process issues Self-organizing design strategies are a necessary and inevitable consequence of the application of open-ended computational thinking to many other aspects of modern life. Hence the architectural form of the office will inevitably become self-organizing and open-ended.

Architecture and engineering will become intertwined, making it difficult to distinguish the boundaries between the two. This ambiguous relationship is potentially productive.

Diagrams are important in both organization theory and architecture. They enable (as well as limit) conceptualization. Since lines have limited utility in displaying fluid boundaries and changing connections, organizational theorists and architects should be experimenting with more malleable graphic tools.

Organizational issues The more businesses are information-based and the more dependent they are on research and development, the less possible it is for them to be managed autocratically.

The “architecture” of business organization is liquefying. Rationalization based on rigid segmentation and specialist work routines within clear-cut functional hierarchies (e.g., Taylorism) is inadequate to respond to the complexity and dynamism of larger socio-economic processes.

Architecture articulates and reinforces social concepts. New relationships between space, society, and ideas should encourage architects to translate organizational concepts into spatial terms (and vice versa) and thus encourage the adoption of novel organizational concepts (and new forms of architecture).

Complexity is good. Building users define and orient themselves and society through architecture. The more complex the social system, the more articulate and conceptual architectural language must be. However, what aspirations were fulfilled and what business objectives were achieved by the striking architectural and urban forms presented in Corporate Fields are not at all clear. What is certain is that most projects in the book are low, amorphic, continuous, flowing. Whether such architectural metaphors on their own can stimulate or only mimic organizational fluidity and change (with possibly counterproductive consequences) is debatable.

Subverting the Supply Chain

Student design proposals are usually untested and untestable. To escape from the conventions of conven-tional office architecture and to turn these ideas into operational reality requires much more:

→ engagement with organizational politics to discover what can be implemented and how;

→ a full understanding of the differences between sectors of the knowledge economy, since not all businesses share the same goals, criteria, or cultures;

→ systematic measures of organizational performance derived from different design propositions in different contexts and circumstances;

→ a much fuller imaginative grasp of emerging working patterns: timetables, mobility, interconnections;

→ a much fuller understanding of what happens in the spaces between organizations and between buildings;

→ better ways of modeling and depicting organizational and social change.

Resistance to change is most strongly embedded in a calcified building supply chain that starts with investors and moves through developers, lawyers, real estate brokers, planners, architects, cost consultants, engineers, the construction industry, interior designers, furniture manufacturers, corporate real estate executives, and facilities managers until it unloads its products on end users. This chain, never known for processing feedback, has created the two globally dominant North American office typologies: High rise offices with their central cores and low rise suburban offices with their deep floor plates and endless arrays of cubicles. Today there are only small signs that change is underway. (For example, in the office design field we often hear presentations about the changing lifestyles of Generation Y, demanding, technologically sophisticated, multi taskers whose attitude to life is summed up by the catch word whatever and how different these are from those Generation X and the even more inhibited Baby Boomers.)

Describing, understanding, inventing, and prescribing a now-appropriate choreography of space use requires conventions still to be invented. They will be. What I am less sure about is whether architects will have the wit, courage, and imagination to challenge, subvert, and replace the existing, increasingly dysfunctional office supply chain. A demand chain that begins and ends with an understanding of user needs is what we really need.