The Haunting Presence of Urban Vampires

The city is the material representation of socio-spatial subordinations to a dominant political economy, a mirror. Its shiny surfaces conceal the asymmetrical struggles that have built it, perfectly masking them behind appealing urban forms and lavish structures, behind elaborate facades and symbolic buildings—urban elements that over centuries have successfully shrouded the oppressive dynamics of capital in the hypnotizing surface appearance made by its infrastructures and architectures.

According to inequality-economics expert Emmanuel Saez, those invisible dynamics have produced an American urban condition in which the biggest gap between rich and poor ever recorded has grown.1 Cities around the globe are also prone to such dynamics, with record levels of unemployment and debt. More than ever, there is an urgent need to understand these conditions, as designers begin to engage the processes that have produced such uneven urbanization. We know about those who design the shiny reflections of capital, but who designs the current dynamics behind the mirror? Corrective processes in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis have multiplied urban poverty to record levels while promoting splashy, award-winning designs. These processes beautify urban cores but simultaneously trigger mass citizen displacement, predatory speculation, gentrification, unsanitary living conditions, uneven property taxation, discriminatory urban policy, and environmental disasters, among other results. These are the divisive elements that contribute to our current global urban crisis.

Traditional urban practices vis-à-vis post-2008 urban prescriptions of nondemocratic, obscure bio-political organizations that design and catalyze processes behind the mirror are futile. Traditional conceptions of design are irrelevant for those who feel the urge to act in this pressing context. Instead, we need to retool and reimagine the usefulness of urban disciplines in confrontation with what is ahead, after, or within the itinerant temporality of crisis.

On the Macro-Economic Directives of Post-2008 Urbanization

On May 15, 2013, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) issued a warning to its thirty-nine-country member base in response to a report, “Crisis Squeezes Income and Puts Pressure on Inequality and Poverty,” compiled from the OECD’s Income Distribution Database. Looking at all available economic indicators from this vast database the OECD concluded that “income inequality increased by more in the first three years of the crisis to the end of 2010 than it had in the previous twelve years.”2 It is important to note that in the same report, the OECD Secretary General Angel Gurría gives a strong warning to all governments, stating, “These worrying findings underline the need to protect the most vulnerable in society, especially as governments pursue the necessary task of bringing public spending under control.”3 In short, the report asked governments to think of ways to continue to implement austerity policies in public spending while developing programs to support the lowest income brackets of the population. In neoliberal terms, these directives always mean more transfer of government social responsibilities to private organizations. The world of private welfare enterprises, whether they are for-profit or nonprofit, is supposed to help ameliorate the inequalities, and thus, governments should seek to implement the necessary reforms to allow these transitions.

The search for the privatization of social welfare comes with neoliberalization, which has a history that spans four decades. It should be of no surprise that OECD reports have actively encouraged economic reforms that have become common practice in most cities around the world. These include the privatization of regional and urban assets, the financialization of urban growth, the promotion of interurban competition, the creation of lax taxation policies for urban renewal developments, and the deregulation of financial instruments needed to produce attractive investment ventures, to mention only a handful.

In the same period, and within the same institutional family, organizations like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank, the African Development Bank, and the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, among others, produced their share of influential reports that, similar to the OECD’s studies, emphasized the importance of urban development for economic growth within countries and continental regions. Consequently, urban development became a primary focus for an increasing number of politicians, lawyers, bankers, nongovernmental organizations, journalists, academics, designers, and other citizens who consciously or not followed this directive—resulting in a radical ideological shift that heralded a new era of urbanization.

This urban era or “age,” as some popular designers call it,4 continues to subjugate most new directives about the city to its logic, from shaping its irresistible spectacle to dealing with the opposite spectrum of its contradictions, clearly evidenced in the seemingly unstoppable buildup of severe afflictions of poverty, injustice, or inequality in urban space, a concern that now appears to be part of the agenda of the OECD and its nondemocratic family of (vampire-like) world-guiding organizations. As the 2008 global financial crisis developed into many other forms of crises, these organizations were slowly forced to recalibrate their free-market views on urban development. It became clear that rapidly rising global urban poverty—in all its social, spatial, economic, political, and environmental manifestations—could not be addressed by private organizations, public-private partnerships, transnational NGOs, and global corporations alone. From whatever “public sector” is left in governments and their vestiges of welfare, these organizations demand the urgent amelioration of unprecedented social inequalities. They propose to do so by “creatively” reversing or rethinking the austerity measures they continue to support, calling for, among other directives, the “restoration of poor and middle income households’ bargaining power,”5 and increasing public spending for employment and social safety net programs. The appeal to all governments is urgent. Failing to address inequality and poverty would pose a very serious threat to global capitalism and the economies of cities worldwide: “The difficulties of doing so have to be weighed against the potentially disastrous consequences of further deep financial and real crises if current trends continue,” concluded the IMF’s research department in a 2013 working paper.6

The ongoing implementation of these macroeconomic recommendations is producing drastic and irreversible consequences within the ecology of cities worldwide, inevitably impacting any form of professional urban practice. Moreover, these vampire organizations are pinning common forms of socially supportive public spending in cities as the culprits of the financial crisis. According to these organizations, government spending on public transportation, housing, health care, education, cultural facilities, subsidized utilities, environmental protection, and other forms of social investment in urban areas with vulnerable populations are to be avoided, as they can create dangerously large deficits that negatively impact economic recovery. The following two summaries from the IMF’s September 2013 fact sheet titled “The IMF’s Role in Helping Protect the Most Vulnerable in the Global Crisis” exemplify these views: “Portugal is implementing a very large fiscal adjustment program, which undoubtedly requires sacrifices from all Portuguese people. Reforms to underpin the adjustment are necessary in many different areas, including taxation and social and health sectors. However, the most vulnerable groups are, to the extent possible, being protected.” And earlier, “[in Greece] a rapid increase in social spending was one of the main drivers behind the large deficits accumulated before the crisis. … Cuts to social spending, including pensions, were therefore unavoidable.”7

Concurrent with these austerity policies, investment in urban development continues to be supported by these regulatory bodies, mainly in three overlapping directions. First, infrastructure projects in impoverished regions yielding large private investment returns are encouraged as a way of stimulating economic growth. According to another IMF working paper, these improvements “not only directly raise the productivity of human and physical capital (for example, roads provide access to remote areas (making private investment possible), but also indirectly, through lower transportation costs which increase economies of scale, productivity, and thus growth.”8

Second, in more developed regions, the continuation of pre-2008 urban infrastructure projects that “enhance urban attractiveness”9 is recommended, particularly those projects that encourage public-private partnerships (for example, the New York City bicycle-share program, which is a partnership between Citibank, MasterCard, and the city’s transportation authority).

Last, municipal governments that opt to partner with private investors for the regeneration of urban areas—doing their part to stimulate the mobilization of capital and the rise in real estate values—are viewed as enacting “best urban practice” and are therefore stimulated by these free-market organizations. The OECD has highlighted two examples: the Grainger Town Project in Newcastle, UK, and the Otemachi-Marunouchi-Yurakucho (OMY) District Redevelopment Project in Tokyo, Japan. According to the OECD, both projects developed a promising speculative market, accelerated gentrification, and made the area more secure for the type of citizens and investors they aimed to attract.10

Strategic private investment has become so common that it is difficult to think of any city that has not followed this path. Examples include Mexico City’s partnership with Carlos Slim to redevelop the city’s historical downtown, and the aggressive planning implementations of the Housing Development Administration of Turkey (TOKİ), which, together with private investors, has been actively targeting dozens of inhabited areas for regeneration. Both have been disastrous for the urban poor, displacing thousands of low-income citizens, threatening their livelihoods, as businesses, schools, clinics, parks, and libraries have been forced to close in order to accommodate profit-generating transformations. According to these free-market organizations and the many municipal governments that heed their suggestions, this managerial form of governance should continue to prescribe the future of urbanization.11 In this sense, pre- and post-2008 urbanization agendas have not changed significantly. Despite the evident poverty and inequality they produce, these policies are still seen as promoting economic growth; they will continue to haunt urban dwellers for years to come.

On Poverty and Urban Vampires

Recognizing that growing inequality and poverty pose serious threats to free-market economies, these organizations perilously ignore the evidence that the type of urbanization being promoted plays a key role in the production of the inequality and poverty they aim to ameliorate by attending to levels of accumulated debt, issues of unemployment, and citizens’ capacities to acquire loans as primary goals. By doing so, they ignore the dire social consequences at the periphery of their seemingly positive pro-growth economic indicators. As Karl Marx noted in Capital, “‘improvements’ of towns which accompany the increase of wealth, such as the demolition of badly built districts, the erection of palaces to house banks, warehouses etc., the widening of streets for business traffic, for luxury carriages, for the introduction of tramways, obviously drive the poor away into even worse and more crowded corners.”12

The process of neoliberalization at a planetary scale has taken place over the past four decades. For younger generations and for those who grew up under its ideological dominance, the idea of scaling back the role of government’s social responsibilities is common. This “fact” no longer alarms the majority of citizens, to the point where it has been naturalized as a part of contemporary life. A consequence of the scaling back has been the rise of private-public partnerships and profit-oriented urban governance structures, as well as the nonprofit industrial complex, which, in many cases, exist to help governments transfer social responsibilities to charity and permit private corporations to play tax games for profits. If state and municipal governments can barely meet the social support exigencies of these capitalist organizations, and the new profit-oriented partnerships that direct contemporary urban growth refuse to intervene in urban areas where little or no profit can be readily extracted, then who is addressing the growing conditions of urban poverty and its socio-spatial consequences? What political and economic mechanisms remain that target the dramatic rise of these socio-spatial inequalities? And, how can we abolish them to make cities more just? It appears that answers to these questions are not likely to be found in the regulating, monitoring, or governing bodies entrenched in the aforementioned capitalist reforms. The lack of concrete direction as to how to sustainably address the urbanization of low-income neighborhoods and less profitable areas has created an enormous void in urban education and its professional practice. It is indeed alarming that there is an immense lack of operative strategies that focus on the urban spaces where the majority of the world’s population lives—that vast gray space in cities where there is little crime, no large-scale development commissions, and no glamorous urban design or architectural competitions.

One would expect that in the extreme conditions of inequality—like the one exposed by the 2008 global financial crisis and its predatory, accelerated, uneven development—most students and practitioners of urban planning would begin to imagine and develop new forms of urban practice and intervention that address the spatial injustices that surround them. But after five years of permanent crisis, the trend continues to expand their old knowledge and practice in the polarized city fields conditioned by it. Why is it that our daily strolls through the city are not enough to catalyze a radical shift in most of us? Every day, we inevitably must exit the imaginary world of the capitalist spectacle and confront the disparity, precariousness, segregation, and exploitation that subjugate the urban life of so many. We walk by the multimillion-dollar mansions, the Michelin-starred restaurants, and the “designer” towers that compose the foreground of the precarious dwellings that surround them; we continuously scramble between luxury cars and homeless people begging to clean them, between exclusive storefronts and VIP entrances serviced by minimum-wage workers; we redirect our paths within gated areas, avoiding confrontation with the illegal immigrants that maintain them; we stroll by the high-end shops selling products manufactured in slum factories in Bangladesh; and we zigzag between superfluous products and services that encroach on what used to be public space. What more awareness of spatial injustice, urban poverty, and inequality do we need than the visuals of our daily commute?

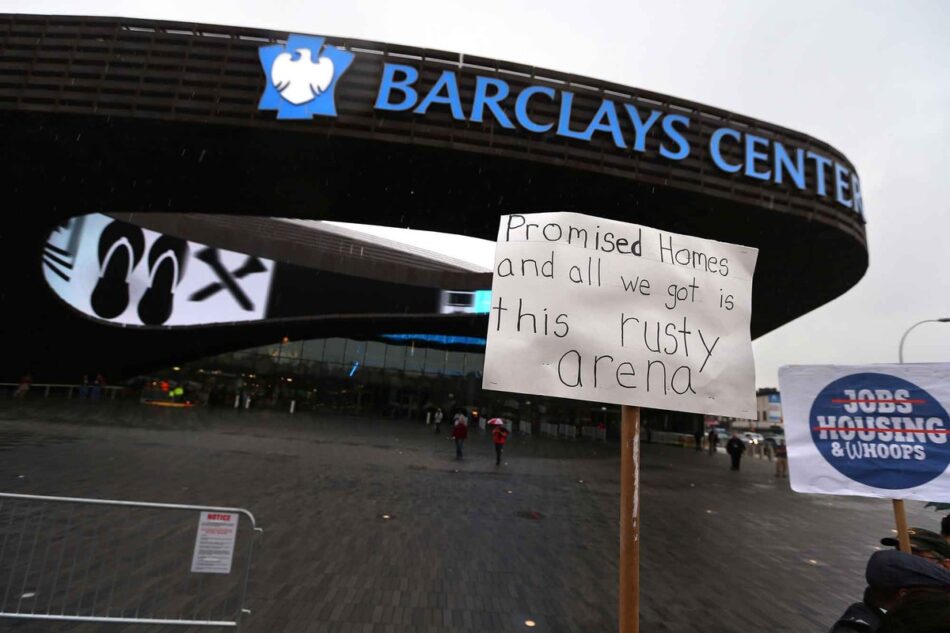

We celebrate predatory forms of urban development regardless of the fact that besides producing all the known perils of gentrification, they legally suck public money and resources into private hands. Examples of projects are numerous: the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, built on a large piece of city land purchased for less than half of its appraised value; the Philharmonie de Paris, a 500-million-euro bottomless pit of unfinished metal pieces designed by Jean Nouvel; the dramatic transformations in Brazil’s major cities in preparation for the Olympics and World Cup; Istanbul’s plans to convert the symbolic public spaces of Gezi Park and Taksim Square into a shopping mall. These daily confrontations between public and private interests and economic and social disparities spatialize contemporary class struggles and the ways in which cities enact and reinforce inequality; they are the most perfect mirrors of the capitalist system, manipulating the accumulation of our daily surplus. But be very aware: vampires cannot see themselves in the mirror, they do not have a reflection; vampires can only perceive and reproduce the world in their own image, and it is this incapacity that feeds their contagious ambition.

Why do we continue to praise designers who are complicit with the production of urban poverty? To a large extent, urban planning and design practices traditionally accommodate very little intellectual and practical knowledge that could help understand, let alone respond to, such urgencies. In academia, where one would expect to find new advances toward spatial justice, most practitioners are so entangled with the ways of the vampires, that much of what is taught is done so to propagate the detrimental tools and skills at the heart of the problem. What should hopefully be clear to younger generations is that if they blindly follow the ways of the vampires, our urban futures will most certainly expand on Mike Davis’s chilling dystopian descriptions of a planet of slums, consisting of a few gated paradises “made out of glass and steel as envisioned by earlier generations of urbanists.” But as is already clear, “much of the twenty-first-century urban world squats in squalor, surrounded by pollution, excrement, and decay.”13

Before we continue to delve further into surface appearance and concrete representations of architectonic and urban form, it is essential that we analyze the capitalist processes that have produced those representations. We cannot afford to operate in a world in which we hardly understand its modes of production. This will require an enormous effort from younger generations to enact transformations that host more equitable modes of urban living, which could overthrow the uselessness of what it has been taught vis-à-vis the current conditions of our urban world. Recalling the words of Manfredo Tafuri: “The recognition of the uselessness of outworn instruments is only a first necessary step, bearing in mind the ever-present risk of intellectuals taking up missions and ideologies disposed of by capital in the course of their rationalization.”14