Sculpo, Ergo Sum

Since the early 19th century, physical culture—training, fitness, bodybuilding—has oscillated between the realms of design, art, and politics. Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who established the nationalist Turnbewegung (gymnastics movement) around 1810 in Berlin, viewed physical training as a means to a political end. He aimed to strengthen the state and unite Germans in the face of the French, whom he considered to be effeminate and overcivilized. Functional design and ideological politicization of the body were paramount.

Waves of immigration brought turnen abroad, where it was reinterpreted in less völkisch, more capitalistic, and often eugenic terms. The New York fitness prophet, eugenicist, and tycoon Bernarr Macfadden, for instance, first encountered physical culture through immigrants in Missouri, and through the reformer William Blaikie, who praised the military benefits of turnen in his 1879 How to Get Strong and How to Stay So: “the sweeping work the Germans made of [training] in their late war [… is] good ground for the assumption […] that it was [their] superior physique […] which did the business.” Jahn and Blaikie acknowledged the aesthetics of the body, but subordinated it to political, societal functionality.

A major aesthetic turn took place in the late 19th century, when Prussian-born bodybuilder Eugen Sandow exhibited himself as a tableau vivant. According to his biographer David L. Chapman, Sandow “was the first showman to emphasize physique display rather than lifting weights.” He adhered to eugenics, too, but shifted physical culture away from collective functionality and toward an individualistic aesthetic practice, even encouraging women to hit the gym. In an often racist and misogynistic environment, he was a remarkably inclusive character, especially in comparison to imminent Nazi Germany, where dubious figures such as Hans Súren, a nudist (who, like Macfadden was a proponent of vegetarian eating), of filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler’s Überfrau, ideologized physical culture for a radically exclusionist and chauvinist regime.

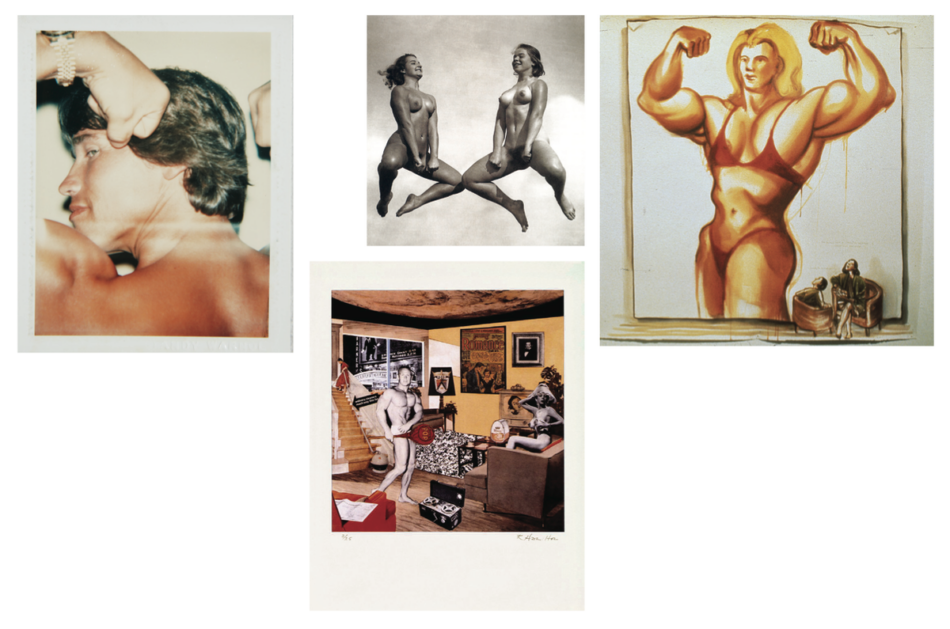

Sandow became the blueprint of Arnold Schwarzenegger—the personification of the artistic turn in libertarian, postmodern physical culture. Schwarzenegger was the figurehead of the first bodybuilding confederation, which judged body aesthetics alone, and developed a multibillion-dollar industry. Despite commodification, the body was now treated as an artwork. Notwithstanding the usual claims to health, or even nation building, the image or art of strength and health became more important than actual strength and health. Schwarzenegger posed in a 1976 bodybuilding exhibition and symposium at the Whitney Museum of American Art, while the first female bodybuilding champion, Lisa Lyon, viewed herself as an artist and freethinker.

It is not surprising, then, that the sculpted body has inspired numerous postmodern and contemporary artists, among them Andy Warhol, Robert Mapplethorpe, Eduardo Paolozzi, and recently Ali Kazma, Mika Rottenberg, and Lea Rasovszky. After all, the cult of postmodern bodybuilding and fitness thrived in parallel with Pop, body, and performance art after 1945. At that time, the former Cartesian subject turned into a project, a performance, an artwork—sculpo, ergo sum.

Jörg Scheller, an art historian, journalist, and musician, is a tenured lecturer and cohead of the photography program at the Zurich University of the Arts. His books include Arnold Schwarzeneger oder Die Kunst, ein Leben zu stemmen (2012), No Sports! Zur Ästhetik des Bodybuildings (2010), and Inter View 1 (2006). Scheller is curator of the forthcoming exhibition, “Building Modern Bodies: The Art of Bodybuilding,” at Kunsthalle Zurich.