Life Begins at the Apocalypse Monster Club

Our band could be your life.

— Minutemen, “History Lesson – Part II” (1984)

We were called Devil Donkey. We were not good, at least not at first, but we had a gig, and it was a doozy. We were opening for the Buck Pets at the Apocalypse Monster Club, a punk-rock club inside a large warehouse space next to a Corvette repair shop, just across Highway 3 from NASA’s Ellington Field in Houston. The Buck Pets were everything we were not. They were a loud noise rock band from the Deep Ellum scene in Dallas that eventually signed to Island Records. They had nice guitars and huge amplifiers, spiky hair and studded leather jackets with the words “BUCK PETS” spray-painted on the back. We had homework. We went to debate tournaments. We had marching-band practice in the afternoons. We had track meets. We were four kids who went to a large public high school near NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston’s Clear Lake City community. It was 1987, and the Apocalypse Monster Club was more than our weekend haunt for punk shows. It was our launching pad, a promontory from which we projected ourselves into the vast terrain of Houston.

We could have been teenagers beholden to a city in its interminable present. We could have railed against its laughable public transit, its general spread-out-ness. Houston was humid, its air heavy, yet it vibrated to the sounds and pulses of nervous, giddy potential. The pitch-perfect paean to the only city we knew could have been taken straight from Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture: The Avowal (1972) by Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis with Madelon Vriesendorp and Zoe Zenghelis: “Nothing ever happens here, yet the air is heavy with exhilaration.” No wonder, then, that of all the images from this project, a photocollage of musicians posing in the “strip of intense metropolitan desirability” resonates with my memories of Houston and its eclectic punk scene. This is an image of youth, preening and haughty, looking less like prisoners and more like Elvis Presley’s back-up band of inmates in Jailhouse Rock (1957). The musicians appear taut and wiry, not bored, but idle, perhaps ready for a fight. Swords have turned into guitars and drums. This is a vision of youthful urbanism. This was us. This was our band. And like the titular dwellers of Exodus, we transformed the city, building a version of it that mirrored our own desires.

We conjured this image against competing narratives of Houston. There were no grids, no obvious icons that moored this city to any idea of a modern city. By the mid-1970s, Houston was expanding in thrall to the rhythms of extraction and exploration: oil booms and moon shots meant increasing rents and more office spaces. Low-slung modernist boxes and midsize Art Deco towers gave way to an archipelago of city centers, each recognizable by a tall glazed tower surrounded by a hodgepodge of contemporary architectural and cultural artifacts. The brackish waters of Buffalo Bayou ran eastward from downtown Houston, through parks, underneath beltways, into sluices and canals, flowing into subdivisions and industrial zones, widening into the estuaries of the Houston Ship Channel and draining into Galveston Bay. This watery meridian joined the Astrodome to the Johnson Space Center, an arc of development marking how “Bayou City” transformed into “Space City.” Yet the Houston celebrated by Ada Louise Huxtable because it “substitutes fantasy for history” had changed by the mid-1980s. Hurricane Alicia brought widespread wind and flood damage to the city in 1983. Combined oil and real-estate busts in 1986 and 1987 replaced Houston’s pelagic infill with unfinished buildings and empty lots. There was also the Challenger disaster. Manned space flight activities once so crucial to the city were suspended.

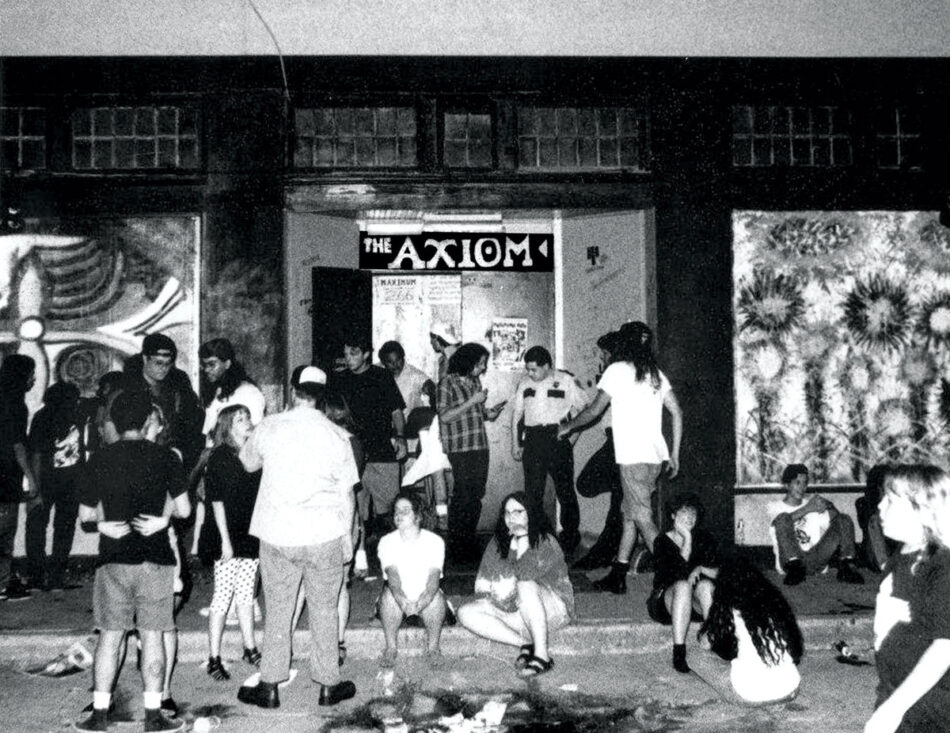

Amid this withering milieu, we reclaimed and repurposed mundane objects and spaces in unfamiliar, sometimes violent ways. Our deviant visual culture borrowed the military equipment and rituals already coded into our high-school lives. We went to 8:00 a.m. calculus wearing combat boots and field jackets sometimes inscribed with anarchy symbols, skateboard logos culled from the pages of Thrasher, or names of bands like Black Flag, Dead Kennedys, X, or Big Boys. Our marching band carried fake guns made of white-painted plywood. This was part of life: going to high school two miles away from NASA and its network of corporate plazas and strip-mall suites with offices for defense contractors. Yet Houston was ours. This is how the Apocalypse Monster Club figured into a punk-rock teenager’s purview. Other clubs like the Axiom, Fitzgerald’s, Cabaret Voltaire, or Numbers; clandestine rehearsal spaces; sweaty taco joints; ice houses: these buildings were nodes in a musical subculture that was visible, pervasive, and alive. Architecture was equipment as important as our cars, guitars, basses, drums, or microphones. All were related to our music. All were part of a city refracted by our energetic, adolescent optic.

Like the desires of other Gen Xers, our architectural desires were born under the sign of Exodus. The photocollages of the guitar- and drum-wielding voluntary prisoners and of the well-known wall incising London ensnare us because they are teeming with possibilities for political and social engagement. In lieu of rekindling our romance for May 1968, a momentary re-inhabitation of our teenage years may be in order. As teenagers, we spatialized our imaginations. We lived in the future imperfect. There is solace in this. On a warm May night in 1988, we channeled Exodus and played our own teenage ode on the architecture by which we were forever enclosed. We loaded our gear into a powder-blue 1977 Cadillac Coupe DeVille and sped off along the Gulf Freeway to play a show at the Axiom, on the east end of Houston’s downtown. We rolled down the windows and listened to a tape of ourselves rehearsing our set. And as we watched buildings and cars turn into blurry fields of light and exhaust, we announced ourselves to the city.

Enrique Ramirez is a scholar and historian of modern and contemporary architecture and urbanism. He is working on a manuscript that considers how exchanges between architectural and aeronautical cultures in 18th- and 19th-century France constructed new, modernized ideas about air and the natural environment. He has also been a recording and touring bassist since his high-school years in Houston.