Puertoricanism, or Living at Ease in the Surface

Puerto Rico…

You ugly island…

Island of tropic diseases.

Always the hurricanes blowing,

Always the population growing…

And the money owing…

1. _You Ugly Island…_

— “America,” from West Side Story

For the first time in over one hundred years of American occupation, there are more Puerto Ricans living on the mainland than in the territory. And for the first time, the population of Puerto Rico is not growing, as Anita sardonically sang in West Side Story, but shrinking and aging at an extraordinary pace (“the money owing” continues). This demographic reconfiguration should come as no surprise; it was planned as part of the same political agreement that created the Estado Libre Asociado in 1952, a status designation euphemistically translated as “commonwealth” for an international audience with no stomach for imperial violence or abuse of power.

That imaginary pact between Puerto Rico and the United States seemingly allowed for the circumscription of local nationalistic sentiments within American military interests in the Caribbean region, packed into a rubric that was ambiguous enough to elude the United Nations’ anticolonial radar for almost sixty years. The complementary “final solution” for Puerto Ricans was to promote migration to the States at a time when a growing industrial infrastructure was in need of cheap, exploitable labor. Since Puerto Ricans were granted American passports in 1917 by the Jones Act—an event that expedited their enrollment in World War I as legitimate soldiers—migration was by then an easy, legal option for them. Three decades after citizenship had been extended, resources in the island were still scarce, and postwar America was, more than ever before, a land of promise and possibility. At the time, migration emerged as a practical measure to address the island’s overpopulation and economic funk.

The messy political circumstance of being part of but not quite—Puerto Ricans on the island are not able to vote for the U.S. president, have no voting representation in Congress, yet are ruled by the sovereign power of that political body—set the tone for Puerto Rico’s current isolation from Latin America and the rest of the world. When speakers address Puerto Rico in front of Latin American or U.S. audiences, a formal introduction to the country’s uncertain political status is customary. The elaborate explanation alienates each audience for different reasons. For U.S. audiences, it elicits a guilt-ridden awareness of Puerto Ricans’ status as second-class citizens; for Latin Americans, it serves as a reminder of the nuisances of illegal immigration, some thing that Puerto Ricans have never had to endure. In each case, the perceived asymmetry of power and privilege contributes to Puerto Rico’s estrangement and consequent otherness.

The need to take a stance on this political scar has conditioned Puerto Ricans’ self-image, providing alibi and pretext for both the crime and its punishment. To relate all cultural conditions to this “scar” has transcended a mere habit to become a national obsession, the unavoidable anteroom for any attempt at identity soul-searching. Issues of identity have dominated conversations on art and culture in the inner sanctum. What would be labeled as a proto-fascist tendency in any other place has become socially acceptable in Puerto Rico as a legitimate, over-the-top expression of nationalistic pride. Loud exuberance passes as a mild, harmless form of political resistance, coming from an elfin island loyal to its assumed off-the-shelf narrative of victim and victimizer.

The good news is that attitudes have been changing in the cultural forum over the last two decades. As it is now, identity is less of a national fixation because newer generations of artists and cultural producers are determined to focus on relatively narcissistic quests, with little space for cultural essentialisms. Architectural discussions, however, have been less successful in finding an analogous voice away from the reductive political conversation, retracting instead to the same old issues of identity struggle and genealogical quest in ways that resemble 19th-century debates on the origin of art and the quasi-Darwinist development of style. I will argue that this self-inflicted narrowness of scope comes as a result of a historical trauma that continues to haunt architecture in Puerto Rico with its collateral anxieties.

Even though tracing the present to a previous trauma could be understood as another brand of genealogical fetishism, I believe that the periodic application of political violence, within a democratic setting that barely hides the asymmetry of power, relevantly restores shock into a present condition, not a distant origin. The calculated oscillation between historicism and presentism that characterizes the discussion of architecture in Puerto Rico among academics and practitioners reflects an elliptical concept of time that has allowed the boundaries of an imaginary notion of the contemporary to spread, which is ultimately the matter I would like to address in this essay.

2. The Chronicle of Space

The first school of architecture to operate on the island was established in 1966 at the public University of Puerto Rico. Architecture had been an important presence in the island before—proponents of the Estado Libre Asociado had already channeled their neo-positivistic ambitions through architecture, turning it into a proselytizing instrument of hope after the alliance with the superpower—but this new prominence in the university system propelled public acknowledgment of architecture’s prospective role in mitigating the darker side of development. Even though this endorsement was already in crisis due to the wearing out of late Modernist dogmas and the emergence of neo-avant-garde sensibilities in the Western world, the optimism brought on by the ability to graduate architects from a local program extended the life of Modernist convictions for a while longer. It was already evident that, in spite of the close relationship to the United States, new narratives and stances coming from the American academia arrived in the island after noticeable delay.

Puerto Rico has always fallen a little behind schedule in its imagined development trail. The American invasion at the turn of the century and the ongoing occupation since the end of the Spanish-American War accelerated things a bit, but the definitive turn came in the 1950s with the almost simultaneous enactment of an industrial revolution and a postindustrial contraction. Puerto Ricans learned to produce and consume, centralize and decentralize their population, all at the same time. This anomaly led to uneven development, leaving pockets of cultural and economic hypertrophy everywhere. That a new school of architecture in the early 1970s was still invoking Modernist idealism and social redemption in its teachings was just another example of this uneven growth.

In principle, the new professional degree program in architecture might have stimulated the search for epistemologies attuned to the island’s self-image as the epicenter of an economic miracle that took place in the ’50s and early 1960s. In reality, the school remained stuck under the orthodoxy of Modernist determinism (the whole package: function, material, and structure) for roughly fifteen years, far away from the emerging interest in architecture as a cultural field fully embedded in an economy of signs and symbolism.

In the early 1980s, the struggle between late Modernism’s “virtuous” practitioners and its “Dionysian” detractors from the Postmodernist camp set into the adolescent architectural program, opening a new phase of vitriolic debate that sometimes acted as a stand-in for ideological warfare between the two reigning political parties, the pro-statehood party and the estadolibristas (pro-commonwealth). The former clung to a debased version of Modernism, plagued by late Brutalist clichés and low-tech interpretations of high-tech detailing. The latter were mostly associated with Postmodern “contextualism” as a way of sublimating neo-nationalistic desires. Looking back at this old feud, one gets the impression that what appeared to be a clash between intellectual standpoints—fashioned in Grays versus Whites antics, with dramatic overtones of generational conflict (cutting edge versus retrograde, etc.) and partisan animosity—was in fact a fight for control over the state’s representation machine, which was experiencing its very own shift.

As the rapidly growing island economy reached a stagnant plateau in the early ’70s, the Modernist signs of progress were no longer delectable to a less gullible audience. Until then, for a government that was and still is the island’s biggest client, engineering infrastructure had been regarded as a more reliable source of symbolic power, with architecture mostly relegated to a secondary gesture of reassurance of public faith in the state’s political and economic achievements. Suspecting an upcoming symbolic paradigm shift on the part of the government—from hard-edged, defiant infrastructural devices to the more inclusive realm of architectural space—architects felt the urge to demonstrate who among them was better suited to develop complex geographies of representation for a visually congested Postmodern environment.

In a sense, this shift from infrastructure to architectural space, masked as a mere change in taste among state officials at the end of the ’70s, symptomized what would be later understood as a widespread reconceptualization of the designer’s cultural role. Architects were led to believe that, after the failures of Modernism, the time had come for their messianic takeover of space, when instead they were being called on to meticulously clad a new topological order developed by others. What mattered, then, was design’s ability to divert the eye from that order, not its technical expertise to produce it.

To better articulate the relevance of this late ’70s symbolic shift, I will elaborate on the cultural condition that titles this article, a chronic complacency with inhabit ing the flattened remnants of architectural space, which years ago I called Puertoricanism, or living at ease in the surface. My concept unambiguously suggested that space is not a symbolic medium to be controlled by architects but a sacred, forbidden realm in charge of engraving a visual strategy of domination, out of reach to those subject to it. I originally came to question the architect’s panoptic assumption of being responsible for deploy ing visual artillery over space after gaining awareness of the intricate political maneuverings of a colonial government struggling to appear postcolonially evolved to its subordinated citizens.

At the time, what I perceived in the island was not a delayed echo of previous events or cultural transformations taking place on the mainland but the first highlights of a new global condition. The analogical relation ship between quintessentially local events and worldwide circumstances has been part of the ongoing history of the Caribbean, a place that has served as an in voluntary laboratory of practices, certainties, and uncertain ties for the powerful to put to test. It is not uncommon, then, for scholars (unintentionally) to identify local traces of what will later be accepted as shared phenomena in the global scenario, occurring for the first time in the marginal accounts of this archipelagic middle world. Puerto Rico, as part of the Caribbean, not only does it better, as the slogan says, but apparently does it first.

In an attempt to deny architecture’s imminent demotion to the realm of the surface, an influential group of architects in Puerto Rico, who would normalize the discussion for the next two decades, proposed “space” as the true court for assessing architectural merit. This glorification of space, however, veiled an alarming incapacity to act on it, to configure it against the economic and political powers in charge of its creation and destruction. In Puerto Rico, space is not a malleable substance of sorts but a limbo of negation and rejection, a depot of impossibility and truncated desire. The more these architects bragged about their masterly disposition of space, the more they were pushed into becoming mere dressers of its sinuosities.

An important source of this fetishistic assertion of space came through a select group of Cornell University alumni returning to their beloved island. For decades, this school of architecture has been idealized by the local bourgeoisie, and it is often quoted as the driving force behind the creation of both the first architectural program at the University of Puerto Rico and the second one at Polytechnic University in 1995. Away from the nihilistic tendencies of Colin Rowe, who was the most important influence on a generation of architects that attended Cornell in the ’70s and early ’80s, these new candidates to the reigning throne of architectural leadership exercised a moral judgment on the history of architecture. Good space came out of a clear definition, as in a traditional room; bad space was the demonized Modern ideal of the universal and boundless extension, the open plan, and the wretched tabula rasa of urban renewal. Rowe’s amoral disposition of an array of spatial utopias without hierarchies or absolute valuation was turned by these colleagues into a righteous theory of composition—infatuated with drawing as the sacred temple of the line and the lineal. To rigidly define, to introduce harmonic order where it had been disrupted, to recover historical continuity where it had been hijacked—that was the architect’s quest. Ambiguity could only be accepted if it was an incidental, exceptional condition, not the norm of an entire system. Of the two most prominent theses put forth by Rowe, these returning ex-students embraced the one that saw in mathematical order the link to a classical ideal, not the one exploring the beauty of colliding indetermination, which is in any case closer to the island’s vernacular incoherence and precarious unity.

This formalistic approach, with its skeptical attitude toward complexity, gradually came to dominate the studios at the University of Puerto Rico, truncating richer cultural readings of architecture at a time when a fertile, interdisciplinary conversation brought on by the irruption of poststructuralism was creating potential windows of collaboration with the university’s liberal arts, sociology, and political science programs. The retrograde tendencies coming from this contrived architectural formalism, incipient in the late Modernist tradition imposed by the founding fathers of the architectural program, reiterated the autonomy of architecture, not to save it from ideology but to submit it to ideology’s own logic in an already sensitive political context afflicted by a century of American imperialism. A strong anti-intellectual bias took hold of the discipline and the practice as a direct consequence of this doctrine. To this day, architectural discussions in Puerto Rico tend to emphasize form over conceptual analysis, historical determinism over present-day experimentation, canonized precedent over emerging condition, sanctioned professional practice over independent thinking—as if protecting architecture from subversive forces of change.

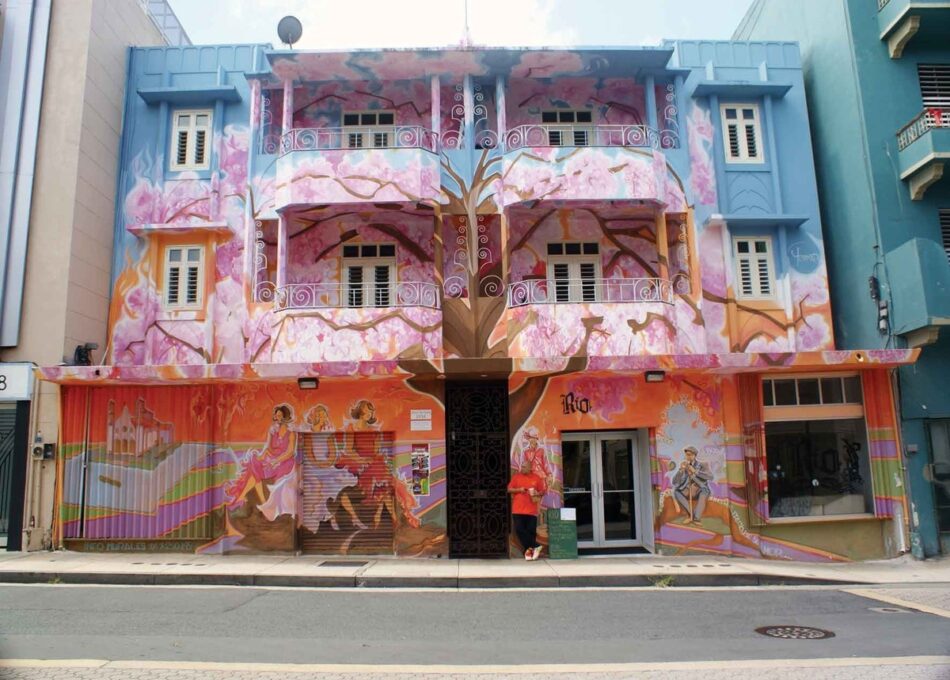

There is a subjacent irony in the fact that this reductive conversation has not improved architects’ capacity to communicate to a wider audience, which was the original motive behind the “Cornell revolution” and their attempted takeover of the island’s architectural debate. Space, their precious instrument of architectural content, was from the very beginning an impossible place in Puerto Rico. Puertoricanism, in this context, is the condition in which power over the production and disposition of space is exercised by the mainland’s military and capital, leaving the surface as the only place for actual inhabitation. While architects turn their back on this condition, the general public, the people (with whatever hierarchies or configurations one may choose to address them), have intuitively embraced Puertoricanism. The flamboyancy of color and texture, the aesthetic of accumulation, the layering of boundaries, the naive prominence given to the unapologetically flat and frontal are the closest approximations to a vernacular gesture. Architects in Puerto Rico have been consistently resisting these idiosyncrasies, focusing instead on curing the architectural artifact from what they regard as a birth defect, for it is considered an anti-architectural proclivity to reject space as the privileged domain of design and composition.

I suspect that beyond the aesthetic debate, there is a political dimension to this neurotic hold on visual culture in Puerto Rico and its plausible relation to architecture. To acknowledge the surface as home is to accept the colonial condition that pushes all autonomous will to the edges. In contrast, to objectify space, emphasizing its limits, is to mask the ambiguities of the prevailing political order, conveying a false sense of freedom that can only be experienced vicariously through architecture. In a way, the anti-aesthetic preeminence of a vernacular flatness is more in tune with a revolutionary gesture than any form of muscular spatialization, since it unabashedly exposes the colonial condition while suggesting new paradigms of composition out of the incoherencies stirred up by the repressed conflict.

3. Modern safety nets

Puerto Rico’s foundational acts tend to favor time over space. The Estado Libre Asociado, for instance, was an event in time, not in place. Throughout Puerto Rico, one can hardly find a ceremonial axis or fixed element that conveys a sense of spatial permanence. Even the creation of the first school of architecture did not produce a new building, recycling instead the former faculty center on the Río Piedras campus of the University of Puerto Rico. I resist believing that adapting the existing building, as opposed to erecting a new emblematic structure, was just a practical administrative decision; I suspect something deeper was at play.

Space in Puerto Rico is a conscious and unconscious reminder of the island’s lack of political power. Puerto Rican time, on the other hand, is open to manipulation and even symbolic inhabitation. History, regarded in Puerto Rico as the ultimate deification of experience, has become a fictional domain where imagination aligns with a preset narrative. History, then, is not where the foundational act gets recorded, but the foundational act itself.

Memories in Puerto Rico are produced in the present and projected toward the past in a process of highly selective taxonomization. Such a flexible concept of history is consistent with the Modernist tabula rasa over time as well as space. Puerto Rico’s attempts to explain itself through history, rather than restoring a linearity of suit able events organized in accordance to a consensual past, have produced a convoluted diagram of retroactive projections experienced in the present. In other words, the invention of history is not so much an act of selective restoration of the past as a reconfiguration of the present imagination.

Puerto Ricans allow themselves to feel in the present the emotions that they should have experienced in the past but did not, as if pursuing the restoration of a biblical continuity between two testaments. The 19th century acts as the first testament to a national epic and is retroactively perceived as the temporal center of a trauma fed by a sense of incompletion (incomplete nationality, incomplete cultural identity, and so forth). Monumentality, for instance, as an architectural sign of 19th-century nation-state building, serves as a reminder of a primal dearth and is reconstituted today in an attempt to exorcise the persistent sense of delayed arrival. Present actions attempt to rid the 19th century of its traumas, some times so literally that one might feel compelled to use the term “therapeutic reenactment” to describe the distinct brand of contemporary architectural monumentality highly admired by the local audience.

Postmodern historicism provided an efficient vehicle for distilling this national insufficiency. Stripped from its ironic eclecticism, Postmodern historicism took its role as manufacturer of memory very seriously, partnering with the conservationist movement and often blurring the line between real and embellished history. The political value of resurfacing history—or just inventing it with narratives of origin and triumphant evolution—reasserted the role of the architect as the master producer of the spectacle of the past. The ultimate goal was to resignify the present.

Modern architecture, on the other hand, became problematic for this historicist, neo-nationalistic agenda. Back in the ’50s, the perception of Modern architecture was conveniently transformed by the brand-new locally elected government of the Estado Libre Asociado from an ambiguous sign of domination to the testimony of a new national identity that stripped it from its oppressive past. At the time, the future appeared as modern as the new national anthem, which redressed the old revolutionary call for independence with new lyrics but kept the original score.

Three decades after the proclamation of the Estado Libre Asociado, there remained a persistent unevenness between the graphic ornamentalism of the 19th century and the abstract forms of modernity. Both traditions would now become eligible candidates in the national iconography contest that was about to unfold. While the former was easy to pictorialize, the latter, with its insistence on the infinite and boundless void, produced a rather weak image. Modern architecture, in order to find legitimation as a carrier of identity content, needed to expel its elusive photographic self and reassess its connection to the “tangible” past. An evolutionary approach, of the kind that helped Colin Rowe reconnect heroic Modernism to a historical continuum, was helpful here in restoring a link to an “organically” developed national identity. A gesture in Modern architecture in Puerto Rico must be discovered with “chromosomal” bonds to the past.

Nineteenth-century architecture was pried open to nationalistic interpretations through custom-made research. A whitewashed version of its historical meaning tried to connect the unintentional parody of Eurocentric models to the local bourgeoisie’s aspiration for freedom and entrepreneurial audacity, values that were later adopted as rightful collective traits. For a majority of architects on the island, this architecture represents the origin of a visual identity, one that is associated with the sparks of a national ruling class embellished with pioneerist rhetoric. Recent historiography of Modern architecture has tried to emulate this narrative format in an attempt to validate Modernism as a contributor to national identity; a spark of cultural “authenticity” within its morphological experimentation needed to be found to serve as canonical evidence. In recent years, this spark has been evident in accounts of the so-called adaptations of the Modern glass-clad artifact to the demands of tropical weather. By over-emphasizing these gestures of introduced nakedness as foundational acts in space—the realm of impossibility and insufficiency—Modern architecture has emerged as vernacular as 19th-century melting-pot eclecticism. To claim a “vernacular gesture” in the reverse adaptations performed on the Modernist artifact is another example of finding identity in the surface. Space remains a forbidden zone.

The shift from a long-standing Postmodern romance with historicism to the timeless sobrieties of today’s dominant “Neo-Modernism” must be accounted for to address the status of an architectural imagination of the contemporary in Puerto Rico. I will use an anecdote regarding the Puerto Rican Pavilion at Seville Expo ’92 to speculate on this. This building, which came to exist as the result of a local competition to provide a representation of Puerto Rico in the international arena, was described by its authors as the encounter of three symbolic forms: the old colonial fortress, the open frames of modernity, and a rounded podium for an antenna intended to symbolize telecommunications as an antidote to isolation, the ultimate Puerto Rican disease. The authors, Sierra Cardona Ferrer, were heralded at the time and even now as exemplary providers of corporate architecture in Puerto Rico. Segundo Cardona, the firm’s design force, is a member of the first graduating class of the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Architecture. His design sensibilities are steeped in the late Modernist ideal of the old school, evolving from a late Brutalist style to a rather insipid Neo-Modernism with a generous inclination for decorative features. The Puerto Rican Pavilion at Seville was a chance to stretch his signature Modern frolics into the realm of symbolic monumentality. His intention was achieved not through the design, as he envisioned, but against its very nature.

An accident unleashed the symbolic miracle. As the summer peaked, the Puerto Rican Pavilion became a sort of after-hours destiny for its program of Afro-Caribbean music, something originally planned to play a secondary role in the pavilion’s cultural offer to the point that the design itself had made little provision for this magnificent show. Puerto Rican government officials in charge of conceptualizing the pavilion’s program had focused on what they considered the country’s most “aspirational” artistic modes in an effort to please the perceived appetites of an international audience. Against any highbrow projection, salsa music became the real success at Seville, and in one of those wild evening concerts, segments of the glass platform over the reflecting pool that was part of the entrance sequence (later used as an improvised bandstand) collapsed under the impact of the dancing musicians. I am open to believing that this was the true foundational act of Puerto Rican identity, so strong that no architecture could have contained it. The episode quite literally represented a break with old Modernist certainties that were forced to play an unsuitable symbolic role. Ironically, form and function were out of sync at the Puerto Rican Pavilion, whose popular success came out of a programmatic rebellion against the contrived geometries of its design.

One would have expected the disappearance of Modernist formalism from the menu of local architects after the Seville collapse, but no. A younger generation of architects connected with contemporary Spanish architecture and its critical regionalism, and an even younger generation engaged Rem Koolhaas’s original critical standpoint favoring a vernacular, everyday life Modernism. To this day, an elegant yet uncontroversial Neo-Modernism binds together three generations of architects, providing a safety net for architecture’s unsuccessful attempts to tame ideology in the sensitive terrains of colonial domination.

To physically or conceptually escape the island’s miseries has become the true agglutinator of a collective will in the 21st century. Architecture, to maintain its symbolic relevance, needed to embody that fantasy of radical departure with no return. As expected, the historicist quest for roots was displaced by Neo-Modernist negation and its consequent exotizations, which were perfectly suitable to the deluded national self.

In any case, the lesson of Seville was not assimilated. Buildings are designed in Puerto Rico, more than ever before, to oppose subjective inhabitation. The accident at Seville came as a result of rejecting the architectural program—not the neutral list of needs but the social occupation of the multitude, with its disjointed, convoluted display of conflicting desires. Architects, particularly the Neo-Modernist alliance of three successive generations of practitioners, are blind to the Seville faux pas, if not completely oblivious to its perpetual reenactment in slicker robes.

Strangers in their own land they ought to be.

4. The Future on Hold

The fluid, software-induced morphologies of contemporary architecture are at odds with Puerto Rico’s stagnant fascination with the Maison Dom-ino, which has been unconditionally adopted both culturally and technologically since the 1940s. Newer generations of architects have accepted the “impossibility” of space, turning their investigation to envelopes and surface articulation in ways that suggest a latent nostalgia for romantic Modernism à la Edward Durell Stone. The work of Nataniel Fúster fits into this category. Through recovering the architectural wall within a Modern syntax (not unlike what Kahn did), this product of a new breed of Neo-Modernist local architects has been able to improve the photogenic qualities of the object. The international media machine got the hint and responded with numerous editorials. Fúster’s work is most interesting when it formally addresses the grotesquely incomplete—as if reflecting on the incongruous nature of the context—and less engaging when it plays homage to Brazilian Modernism. His work is becoming too small for the themes he seems to be exploring; a congested, unintentional disarray of forms works against his projects’ best features. Fúster has accepted the dictatorship of reinforced concrete, since it is the most readily available construction material; he is struggling, though, with the gradual loss of local craftsmanship. His is a nostalgic quest, elegant in its result, but ultimately cursed by its revisionist intentions. The jury is still out regarding his future, and I sincerely hope for the best.

From the older architects who constitute the local establishment, one detects a chronic incapacity to handle the large scale. Their urban design considerations seem to be rooted in the 19th century, longing for a monumentality that ends up looking like an overinflated small idea. To make things worse, the increasing cost of urban land has been raising building budgets, compromising the scope of allowable finishes and materials. The situation is making mediocre Brutalist buildings from the ’70s look like carefully detailed works of art.

In spite of prevailing protectionist laws, the island has been invaded by American corporate offices with portfolios of dubious artistic merit. It is a plague when the most ambitious projects are commissioned to monstrous corporate giants with little attention to the cultural, technical, or artistic challenges of this heavily idiosyncratic place.

The worst enemy, though, has come from within, in the form of an asymmetrical struggle between a younger generation of architects—uncomfortable with the overnormalizations of professional practice—and the local architects’ guild (Colegio de Arquitectos y Arquitectos Paisajistas de Puerto Rico), which has not been shy to show its disdain for experimentation and progressive thinking. To justify the guild’s reactionary stances, some of its members argue that the guild feels vulnerable against the present government’s record of dismantling any form of opposition coming from militant professional associations in other fields. The government, controlled since 2009 by a textbook neoliberal elite, frontally attacked the lawyers’ guild through aggressive legislation and appears to be on its way to take care of the architects and engineers as well. The tensions have been accumulating in recent months, impelling many young, talented architects to move off the island after being exposed to the toxic work environment.

The relationship between the architecture schools and the Colegio de Arquitectos does not show the courteous antagonism that should be expected. What one perceives now is a unanimous choir of conservative voices at both ends who, suspecting that their time is out, anxiously obstruct new ideas and questions that would move the discussion past their narrow comfort zones. The resistance of an entire generation of baby boomers to play a role other than that of the sole arbiter of value has become a devastating internal obstacle that adds to the estranged political environment of a colony increasingly surrendering to forces from without as well as within.

Amid these turbulent waters, Puerto Rico returns to the same old question: architecture or revolution? We’re missing both.