In the Shadow of a Giant

Fame and celebrity are, ultimately, techniques of abstraction. In societies grown complex, they work to focus attention, and, like all abstractions, they simplify complicated circumstances, allowing us to deal only with who or what “matters.” The mechanisms of public and professional acclaim must necessarily discriminate. In a field such as architecture, there is not enough “media space” for all practitioners to be fairly represented. Since there is no governing body of independent critics—critics untainted by the need to sell magazines, to make academic reputations, or to market their own professional work—assigned to assess the output of each architect, the apportionment of fame is never fair. However, even when the works receiving attention are deserving, as is usually the case with architectural reputations sustained over a century or more, our focus on some must necessarily cause us to ignore others. This seems to me one of the most dubious aspects of the architectural canon: not that the canon might contain undeserving works (of course it does), but that in shining so bright a light on a few buildings or projects, others are unjustly eclipsed.

On the Consequences of Canonization

This is a drawback common to all the abstracting instruments we architects employ. Not only do we have no way of knowing whether our discriminating choices have been the right ones, the very act of discriminating, of including or excluding, exaggerates differences. The canon distorts the field of architectural production much as the evening news sensationalizes the day’s events. Thus my purpose here is not so much to debate the merits of a canonized work, but to examine such a work in order to see what its exalted status has revealed and—more important—concealed. The question to be considered is this: what are the effects of the “overshadowing” that occurs when an architectural work is caught in the glare of media attention, professional praise, and historical commendation? To answer it, I have chosen to study the impact of a celebrated building by an architect who cast—literally and figuratively—one of the largest shadows ever to fall on the professional landscape.

Toward the end of the 19th century, no architect basked in the glow of adulation more completely than did Henry Hobson Richardson (1838–1886). According to architectural historian and Richardson biographer James F. O’Gorman: “[In 1885] he bestrode his profession as its most colorful and influential member. . . . During the spring of this year his colleagues nationwide picked what they thought were the ten best buildings in the country. Works by Richardson took up half the list, published in June, and his Trinity Church, on Copley Square in Boston headed the lot.”1 After his relatively short life had ended, Richardson—whose popularity with colleagues and clients owed nearly as much to his winning personality as to his talent—suffered no loss of ranking. Indeed, Richardson was one of the few 19th-century American architects able to maintain high standing after the rise of the Modern Movement.2

If Richardson was unchallenged in his day as America’s most respected architect, his opinion of the greatest among his works was similarly decisive: “If they honor me for the pygmy things I have already done,” he asked, “what will they say when they see Pittsburgh finished?”3 Richardson was referring to his designs for the Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail, two related buildings that were to be built on adjacent sites in what would eventually become the government district of the city. Richardson had won the commission for these buildings (in February 1884) in a competition among five invited architects.4 His contemporary and first biographer, Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, noted that Richardson suspected he was destined for a short life, and “was almost feverishly anxious to see the Courthouse complete before he died.”5 She reported that Richardson considered the Courthouse “as the full expression of his mature power in the direction where it was most at home.”6

It was not just the scale of the Courthouse and Jail commission that caused Richardson to believe it dwarfed his previous accomplishments. Indeed, his Marshall Field Store in Chicago would be more massive, his Trinity Church perhaps more prominent in its surroundings, and his Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce and Albany Capital buildings nearly as monumental. What the Allegheny County buildings offered was a chance for this architect, at the peak of his fame and creative powers, to pursue the design of a programmatically complex landmark building in a city Richardson was just beginning to view as a fertile market for his services.7 The opportunity to celebrate and facilitate the cause of justice, on a desirable site (the crest of what was then known as Grant’s Hill) in a booming industrial metropolis, must have been viewed by the ailing forty-six-year-old Richardson as one of the few remaining challenges worthy of his talents.

For the most part, historians and critics over the last hundred and fifteen years have not disagreed. Boston’s photogenic Trinity Church may more readily appear in historical surveys,8 and the demolished Marshall Field Store may have been more useful to those, such as Henry-Russell Hitchcock, who wished to portray Richardson as a proto-Modernist, but no critic of whom I am aware has debated Richardson’s assessment head-on. The Jail, in particular, has been extolled by architectural observers for its bold massing, lack of ornament, and extraordinary materiality. Hitchcock called the granite wall surrounding the jail “one of the most magnificent displays of fine material in the world”9; and he reflected what would become the majority opinion when he wrote “the jail is more successful than the courthouse” (although he added “of course, [it was] a much simpler thing for Richardson to design”). Most renderings of the two buildings produced by Richardson’s office, in which the Jail is nearly obscured by the Courthouse, suggest that Richardson thought otherwise, as did Van Rensselaer, who expressed the view that the Courthouse was “the most magnificent and imposing” of Richardson’s works. From the description he supplied with his competition drawings, we can see that Richardson was particularly proud of the manner in which he had distributed the courtrooms and their support spaces throughout the building, and of the way natural light was admitted into the courtrooms from two sides.10 His ingenious (if somewhat exaggerated) justification for the building’s enormous tower was equally innovative: it was to provide a fresh air intake high above Pittsburgh’s polluted streets.11

Whichever of the two buildings one considers superior, it cannot be disputed that together they were very quickly granted canonical status by professionals and interested observers alike. The critic Montgomery Schuyler, writing in 1911, placed them “among the chief ornaments of any American city.”12 Of course, the rapid assimilation of these buildings into the canon, and the position they have attained alongside a few of others regarded as Richardson’s best works, owe partly to the tragic circumstances of their realization. Despite Richardson’s “feverish” desire to see them concluded, his death (attributed to Bright’s disease) occurred when only the Jail was near completion. It would be another two years until its companion was ready for occupancy, and it was Richardson’s successor firm, Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, that oversaw the completion and furnishing of the Courthouse.

Evidence that the buildings were considered extraordinary even before they were finished can be found in contemporary coverage by the Pittsburgh news media. For example, as the nearly completed Courthouse tower was attaining its full 318 feet of height, a local newspaper observed: “The beauty and dignity of the great building dwarfing all other structures in its vicinity cannot fail to arouse a desire for better things in architecture. The new Court House silently but eloquently exerts a potent influence. As a court of justice it tells of the majesty of the law; as a thing of rare beauty in granite it preaches the gospel of better architecture in the Iron City.”13 That even the industrial barons who held the reins of Pittsburgh’s sooty economy recognized Richardson’s achievement can be confirmed by examining the resolution adopted by the Allegheny County Commissioners, little more than a month before the Courthouse was dedicated. Noting the many requests from the architect’s “friends and admirers” in Allegheny County for a suitable tribute, the Commissioners resolved to place the following inscription in the building’s great stairway: “In memory of Henry Hobson Richardson, Architect, 1838–1886—Genius and training made him master of his profession. Although he died in the prime of life, he left to his country many monuments of art, foremost among them this temple of justice.”14

Having compiled this brief account of the circumstances surrounding the elevated reputations of both Richardson and the Courthouse and Jail, I can return to the question that is my main interest: What has been the consequences of this canonization? What, for example, has resulted from the “masterpiece” designation bestowed upon these buildings? What have such judgments meant to the buildings themselves, the city they occupy, and to our present-day architectural awareness?

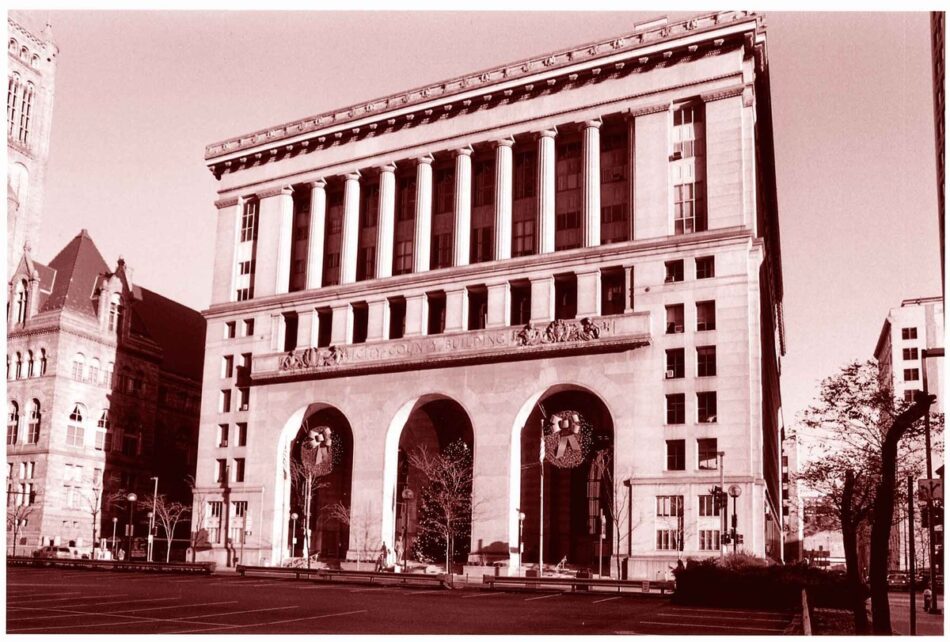

One of the most important consequences of the canonization of the Courthouse and Jail has been the unwarranted overshadowing of another excellent building. The exuberant monumentality of Richardson’s two structures, coupled with the fame of their architect, has blinded most observers to the existence of an equally remarkable structure that is their neighbor. The Pittsburgh building that today offers the most relevant lessons in civic architecture is neither the Courthouse nor the Jail, but an historically obscure edifice standing approximately eighty-five feet south of them. This structure, little known outside Pittsburgh and scarcely appreciated within it, is the City-County Building, credited to the Pittsburgh architect Edward B. Lee in association with the New York firm Palmer, Hornbostel & Jones. On January 20, 1914, it was announced that Lee’s team had bested fifteen others in a competition judged by architects Paul Cret of Philadelphia, John Donaldson of New York, and Burt Fenner of Detroit.15 Construction on the building began in July 1915, and by December 1917 the mayor was able to move into his suite. It took an additional year for the building to be fully furnished and occupied. The structure provided the city and county governments with about 500,000 square feet of office space, and it cost slightly less than $2.8 million (unfurnished).

Edward Lee (1876–1956) was a Harvard-educated Pittsburgh architect who frequently worked in association with other firms. It is assumed that his role in the design of the City-County Building was secondary to that of Henry Hornbostel (1867–1961).16 Among the circumstantial evidence supporting this conclusion is the Hartford Municipal Building (ca. 1912). This commission, also awarded through a competition, teamed Hornbostel’s firm with Hartford architects-of-record Davis & Brooks. While the exterior of the building has little resemblance to anything by Hornbostel, the interior contains a dominating central circulation space similar to that of the Pittsburgh building.17 Hornbostel’s designs for several campus buildings at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), particularly the Fine Arts Building, also contain monumental central organizing spaces. The glazing that occupies the three-story-high arches on the Grant and Ross Street facades of the City-County Building also resembles that of Hornbostel’s buildings at CMU. In the case of the government building, ingenious walkways with glass floors, sandwiched between exterior and interior walls of glass, cross the central arches at the second and third floors. This innovation, which allows the municipal worker to be poised between views of the city and of the interior hall that is its microcosm, is characteristic of Hornbostel’s inventive imagination.

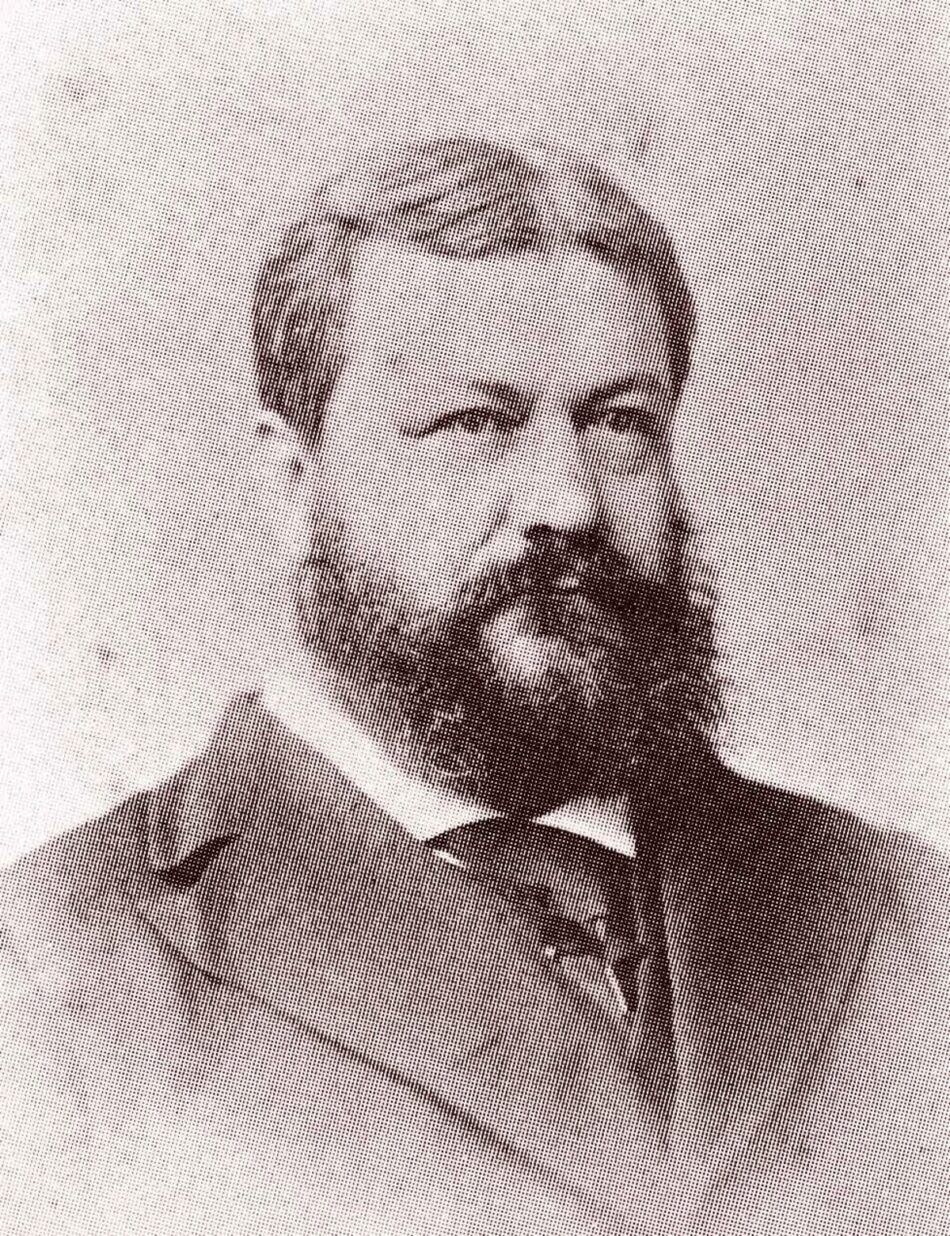

Regardless of these similarities to his past projects, it is Hornbostel’s reputation as an extraordinarily innovative architect that has convinced most of the critics who have studied the City-County Building to attribute it to him. History has relegated Henry Hornbostel to the second tier of celebrated American architects. Although well known while he practiced, particularly for his record in winning competitions—“he won more consecutive major national competitions than any other American architect”18—today he is not much known outside Pittsburgh. Hornbostel graduated from Columbia University in 1891; from 1893 to 1897 he studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.19 In Paris, his classmates bestowed upon him the honorary title l’homme perspectif for his drawing skills. Back in New York, Hornbostel taught at Columbia, while also working as a partner in a succession of firms. Due to his success in competitions, his practice was national in scope. His better known works include the architectural accoutrements to New York’s Williamsburg, Queensboro, and Hell Gate bridges, and government buildings in Oakland, California; Albany, New York; and Wilmington, Delaware. Besides his campus designs for Carnegie Tech, he designed portions of the campuses at the University of Pittsburgh, Emory University, and Northwestern University. He first came to Pittsburgh in 1904 after winning the competition for the Tech campus, and eventually became the first head of its architecture department. By the time he designed the City-County Building, Hornbostel had established a second base of practice in Pittsburgh.

In at least two ways, Hornbostel’s City-County Building is indebted to Richardson’s nearby buildings. First, there is the “potent influence” of the Courthouse and Jail mentioned in the newspaper article cited earlier, “preaching the gospel of better architecture” for the city. Richardson’s works set such a high standard that they no doubt influenced the government officials in charge of the new building project to organize a design competition in hopes of complementing, if not matching, it.20 Second, the City-County Building borrows from the Courthouse the arrangement of the monumental arched portals of its facades. Three portals designate the Grant Street fronts of both buildings; a single portal on each responds to the smaller scale rear facades facing Ross Street. The City-County is also sheathed in granite. Unlike that of the Courthouse and Jail, however, its stone is gray and smooth. There are other significant differences. The City-County is flat-roofed; its side elevations are almost brutally simple, especially since the crossing arcade and grand side entrances shown in the competition drawings were eliminated in the actual building. Whereas the Courthouse was conceived as a monument that would also contain useful spaces, the City-County was a box that emulated commercial office buildings in its massing and exterior appearance.

Like the Courthouse, the City-County occupies an entire city block. However, the two buildings engage their surroundings differently. The City-County Building has an enormous loggia facing Grant Street. The ceiling of this three-story space is vaulted and clad in Gaustavino tile, and its other surfaces, and those of the staircase leading up to it, are of the same gray granite as the building’s exterior walls. What the loggia offers, somewhat surprisingly, is a mediating zone between the city and the building’s interior great hall. This porch space is just deep enough to gracefully handle the transition from street to interior. This mediating zone has served both as a staging area for community activists and protesters—a place to assemble before proceeding inside—and as an impromptu stage from which politicians can address the public. Indeed, the lower portion of the building’s Grant Street facade can be read as a proscenium, facing out to the city. When I worked in the building during the early 1980s, Pittsburgh’s popular Mayor Richard Caliguiri would often meet with members of the press in the loggia. Hornbostel created here a secular American translation of the Old World piazza in front of the cathedral. The space is perceptually “outside” to the extent that it seems to belong to the citizenry more than to the municipal government. Yet it is clearly within the sphere of the government’s influence. It is the kind of permeable, liminal space that seems to promote exchanges between the potentially hostile parties on either side of it. In contrast, the Courthouse was designed to usher the visitor quickly inside the building and up its grand staircase.21 The space is imposing, and delightfully indeterminate, with its intertwined layers of arches and symmetrically paired runs of stairs. It is, however, an unambiguously interior, controlled space, promoting reverence rather than interaction.

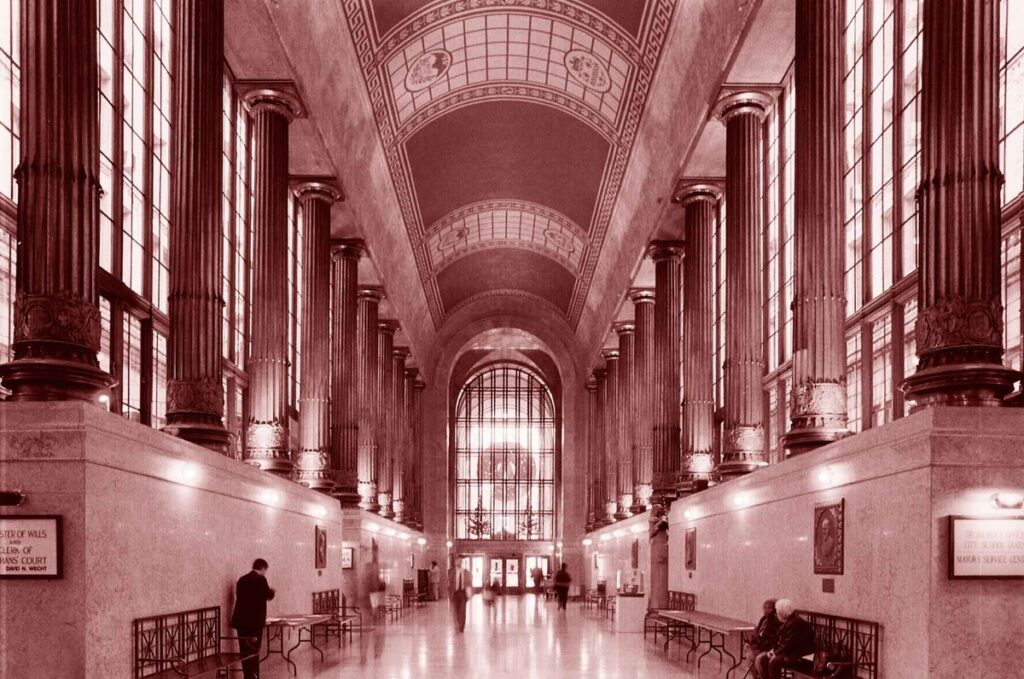

If the covered entry of the City-County Building can be understood as both piazza and porch, the interior space it leads to can just as clearly be considered a street. This great hall extends the length of the building, connecting Grant Street to Ross.22 The hall is thirty feet wide, and it is topped by a forty-seven-foot-high, barrel-vaulted ceiling. While the loggia creates an indeterminate zone between outside and inside, the interior street attempts to create an idealized “outside.” This illusion is possible because the City-County Building contains an enormous light well extending from the second floor through the roof above its ninth floor. The great hall, being somewhat more than three stories tall, protrudes upward into the light well, allowing large clerestories to illuminate the interior street from either side. At the first floor level, the marble-lined street is flanked by a series of “row offices” that contain the public services most often visited—the register of wills, marriage license bureau, tax office, etc. These offices form a “solid” base on which rests the bronze classical columns that support the vaulted ceiling. During business hours, indirect light comes through the clerestory windows, reflecting off the columns and into the “street.” The sense that one is within an atmospherically comfortable avenue is heightened by Hornbostel’s decision to paint the ceiling a deep (sky) blue. While the buildings were designed to satisfy (mostly) different needs,23 Hornbostel’s light well scheme strikes me as a superior solution to the one Richardson used in the Courthouse. Richardson cleverly daylit his courtrooms, but his exterior light court had no real purpose. Originally a kind of service yard parking lot for county vehicles, it was used during Prohibition as a stockyard for confiscated liquor.24 It was not open to the public until 1977, when it was converted into a park, with trees, benches, and a central fountain.

Hornbostel’s light well culminates the interior space of the great hall, which allows the City-County Building to channel most of its public movement horizontally. In contrast, the Courthouse’s light court is purely exterior, making it (in Pittsburgh’s climate) unsuitable as the principal circulation space. The most public interior space in the Courthouse is its monumental main staircase. However majestic this vertical conduit may be, it does not match the easy graciousness of the great hall of the City-County Building, which invites movement. The Courthouse was conceived, to be sure, as less “public” than the City-County Building. Much of the “business” citizens might need to conduct in the Courthouse was required of them by law. In contrast, the lower floors of the City-County have always been a marketplace for government services more likely to attract the casual visitor. My point here is not to claim that one building is superior to the other, but instead to show that it is the City-County, not the Courthouse and Jail, that can teach us more—more that is applicable today—about creating a democratic urban space. If one purpose of the canon is to present us with the finest architectural exemplars, then the City-County Building is at least as deserving of canonization as its famous neighbor.

One indisputable aspect of Hornbostel’s talent lies in his manipulation of the public spaces that form the core of most of his buildings.25 The boundaries between the public and private zones in a Hornbostel building exhibit a range of permeability. In the City-County Building, the activity within its “street” is, thanks to the transparency of the clerestory, on view to most of the upper-floor offices facing the light court. From within the street, the citizens are aware, through devices such as the glazed walkways noted earlier, of the comings and goings of their public servants. The building is, however, no panopticon. The mostly solid, marble-faced walls of its first floor offices restrict views perpendicular to the street. This works to reinforce the street illusion, since the angle of view required to look over these offices and through the clerestory is similar to that which someone in an actual street would need to look over the roofs of shops or houses. Hornbostel characteristically creates spaces that are physically distinct but that, due to the vistas they afford to the outside or to other parts of the building, offer a multiple of places for one’s gaze. At the same time, his central spaces are never so large as to intimidate. Most architects who have been in City-County’s great hall would, I suspect, be surprised to see a drawing of the building’s transverse section. The space that dominates the building is actually quite small when seen in the context of the whole building. Hornbostel scaled his public spaces to make them comfortable to those who occupy them. Thus the thirty-foot-wide street has easily accommodated mayoral inaugurations, flower shows, and Christmas pageants, while still permitting people sitting or standing on opposite sides of it to carry on a conversation.

Another reason why the City-County Building offers lessons applicable to contemporary civic buildings, while Richardson’s Courthouse and Jail do not, is that the latter buildings are no longer feasible to construct. The era when taxpayers could be persuaded to support the construction of monumental public buildings with the awe-inspiring materiality of Richardson’s is long past. The Allegheny County commissioners accepted Richardson’s transparently flimsy excuse for his 318-foot-tall “air intake” largely because they wanted the tower as much as he did. Such blissful disregard of economic reality in favor of symbolism we now reserve mainly for the construction of our sport venues. As the architectural historian Joseph Rykwert has written recently, “Dominant buildings have long ceased to be those in which political and public power resides but are rather those of private finance and corporate investment.”26 Although both the Courthouse/Jail and City-County projects faced taxpayer lawsuits aimed at preventing such “wasteful” expenditures,27 the City-County Building’s design strategy is more adaptable to the fiscal realities of the present day.

A mere thirty years separated the construction of the Courthouse/Jail and the City-County Building. Despite this, and although they occupy adjacent sites, they were born into different worlds. In those three decades the Romanesque style Richardson had almost single-handedly popularized had fallen from favor, and the City-County Building had to be constructed against the sobering backdrop of the First World War. H. H. Richardson had intended his two buildings to dominate the Pittsburgh skyline, but in 1901 Henry Clay Frick built his twenty-one-story office building directly across Grant Street from the Courthouse. Thanks to this “great impenetrable slab,” the Courthouse tower, “symbol of the majesty of the law,” was obscured from most of the city it was designed to face.28

In 1904 Henry Hornbostel came to Pittsburgh to design Andrew Carnegie’s technical school. While there, he witnessed first-hand the power and arrogance of the city’s industrialists. Rather than attempting to compete, Hornbostel gave the City-County Building an anonymous, businesslike exterior. If he could not control the machinations of the city at large, he could plan his building to be a well-ordered virtual city in itself. Into the stark granite box he inserted a self-contained “representative city,” a fitting image for a representative urban democracy. Hornbostel then connected the real Pittsburgh to its microcosm through his complaisant loggia, perhaps the ultimate democratic space, where neither civil servant nor civil disobedient could claim sovereignty. It is interesting to note that the models for the great hall and the loggia, that is, the street and the porch, are the public and quasi-public spaces most indigenous to the United States. Perhaps, then, nothing more complicated than the familiarity of their models makes the City-County spaces so well suited to their purposes. The building is, I would argue, unmatched in its gracious accommodation of its citizenry. And yet it is unknown to most architects. In some ways, Hornbostel’s strategy worked too well. Eclipsed by the greatness of its neighbors, and cloaked in an air of ordinariness of its architect’s own devising, the City-County Building remains unnoticed and unappreciated.

At the beginning of the 20th century, it was still often assumed that architects tended to look like their buildings. Louis Sullivan may have lent authority to this superstition by characterizing Richardson and his work as “direct, large, and simple”—although in the case of Richardson, the conclusion was almost inescapable.29 Boldness and simplicity (of approach, if not form), combined with an identifiable style and expansive physicality, are qualities in both people and buildings that can be readily packaged and consumed. Jeffrey Karl Ochsner has commented upon similar tendencies: “[A]rchitectural historians create narratives that emphasize particular events because they lead to known conclusions. But because this process is selective, the historian of architecture must recognize the inherent tension between the desire to create a structured framework and the desire to recognize and present the more complex and even diffuse context in which design decisions were actually being made. . . . Moreover, that same difficulty is the major impediment to our understanding and appreciating the architecture Richardson influenced. . . .”30

Initially, the Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail took their places in the canon with Richardson’s other celebrated works because—besides their unarguable excellence—they were big, bold, and among the architect’s last works. The Courthouse, not the Jail, was the focus of most of the early publicity, and together the buildings were more widely published than their contemporary, the Marshall Field Store.31 The Courthouse was often imitated, with the most faithful replicas appearing in Minneapolis, Tacoma, and Los Angeles.32 Later the Jail became preeminent, in part because it fit an influential narrative, promulgated mainly by Hitchcock, in which Richardson’s work “progressed” from the picturesque to the nearly modern. Luckily for Richardson, a bridge joins the two buildings, so the one being promoted at any given time tends to pull the other along with it.

The selective processes of history have been less charitable to the architecture of Henry Hornbostel. All architectural movements direct their harshest criticism to that which immediately precedes them. Thus Modernist critics were mostly unable to recognize the proto-Modern qualities of buildings executed in the style of the École des Beaux Arts. Hornbostel’s reputation has labored under a second difficulty as well. Media attention exhibits a weakness for the visually distinctive,33 and history for the ideologically pure. Hornbostel’s work is neither. Furthermore, the single most defining characteristic of Hornbostel’s architecture defies reduction to diagrams or, for that matter, to words. Hornbostel’s buildings, whatever they may look like, are all extraordinarily agreeable, kindly, indulgent.34 Such “immeasurable” qualities are, precisely because they resist transitive measurement, generally excluded from the language of architectural criticism and praise. They are also among the most difficult architectural attributes to replicate,35 and this, more than any other factor, has limited Hornbostel’s influence on later generations of architects.

Many of Richardson’s works had similar qualities. Particularly in his smaller structures, such as the Ames Gate Lodge, and in the public libraries, rail stations, and modest churches, one finds the same atmosphere of benevolence. It is much more difficult to inculcate amiability into a project as large as the Courthouse, or as programmatically intimidating as the Jail (although this quality is evident in the Warden’s House, built into one corner of the Jail’s imposing wall). In the work of Richardson, too, the difficult-to-define qualities that impart humanity to a mute pile of stone have been neglected in favor of other attributes that lead more readily to “known conclusions.” It is ironic, then, that if Richardson had any direct influence on Hornbostel, it was most probably through the example of the Marshall Field Store, that darling of Modernist critics. It is also likely that Hornbostel knew of the store’s progeny, Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Building (1887–89). In many ways, the massing of the City-County Building is remarkably similar to Sullivan’s structure, and each building wraps a distinguished interior space with an anonymous exterior that gives no hint of what lies within.

There are still other connections between Richardson and Hornbostel. Stanford White was an employee of Richardson’s; later on White hired Hornbostel to help in preparing competition drawings for the Military Academy at West Point.36 Richardson designed both the Albany City Hall (1880–82), and, together with Frederick Law Olmsted and New York architect Leopold Eidlitz, he completed several of the buildings that comprise the New York State Capitol (1876-81).37 Hornbostel’s New York State Education Building sits adjacent to this complex, and within sight of the City Hall.38 Like Richardson, Hornbostel was seldom interested in writing or theorizing about architecture. However, throughout his long career as an educator, Hornbostel was often called upon to judge his own and other architects’ work, and in an article summarizing developments in the Pittsburgh region, he addressed the role of Richardson. “If we must choose one man as the greatest influence in the revival of sound architecture and building in Allegheny County, it is likely that we should choose Henry Hobson Richardson,” he wrote. “It is he whom we may thank for the rugged simplicity of our Allegheny County Courthouse and our County Jail. . . . In addition to the two County buildings . . . we have the Emmanuel Protestant Episcopal Church . . . an interesting example of Richardson’s genius, even in small problems.”39

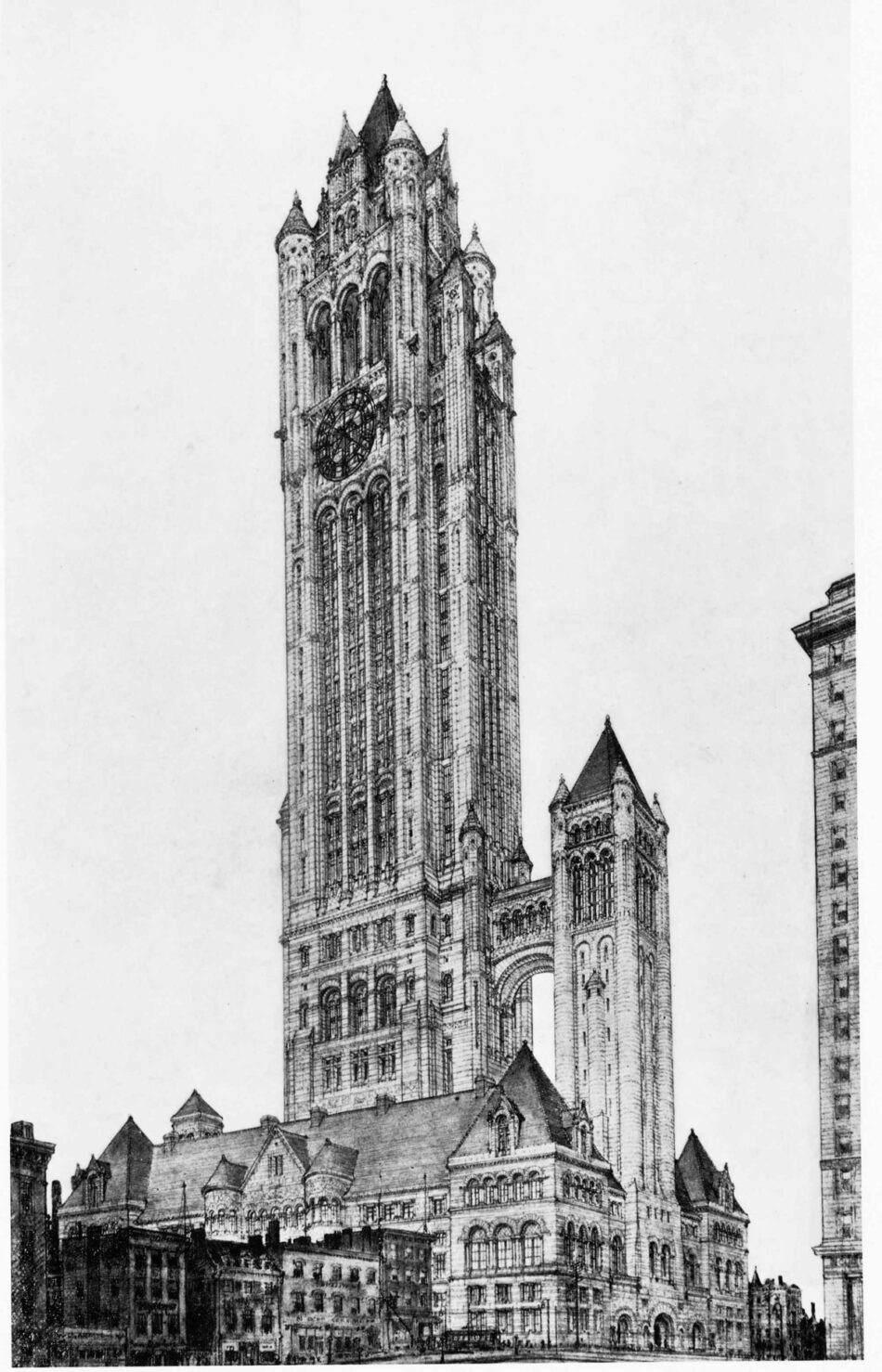

By the time this was written, in 1938, Hornbostel had completed so many significant structures in the area that the obvious alternative “greatest influence” on the region’s architecture was Hornbostel himself. Awareness of this is possibly betrayed in the less-than-enthusiastic phrase “it is likely we should choose.” Biographical evidence suggests that Henry Hornbostel was as magnanimous as the more famous “H.H.” in whose shadow he sometimes stood. It is hard to imagine Hornbostel harboring bitterness toward an architect he so clearly admired. There is, however, one last peculiar connection between the two men—one which suggests that Hornbostel was not above taking a presumably playful poke at his rival. Almost since the Courthouse and Jail were completed, there had been grumbling that the buildings were over-crowded, and before either the City-County Building or the nearby County Office Building were erected, several additions were proposed for the Courthouse itself. The most audacious was one of 1907, by none other than Hornbostel. The scheme consisted of a 700-foot-high tower inserted into the courtyard of the building. A perspective rendering appeared in several architectural periodicals of the day. The proposal was not well received, and there is reason to suspect that Hornbostel was less than serious in making it. Just a few years earlier, Hornbostel spoke out in opposition to a more modest proposal to add a mere two stories to the Courthouse; he suggested that a shotgun be used on anyone who wanted to “mar” a building “too perfect to tamper with.”40 This statement, along with Hornbostel’s career-long aversion to megalomaniacal schemes, suggests that the proposal was intended as a joke. Still, in an episode that could be a standard psychological case study, Hornbostel briefly imagined that his project cast the largest shadow on Grant Street.

However it may have influenced our appreciation of Hornbostel’s building, the canonization of Richardson’s work has not been without benefit for the architecture of Pittsburgh. The fame of the Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail has repeatedly saved the buildings from indignities far less considered than Hornbostel’s attempt at one-upmanship. In 1908, reasonably sympathetic changes to the Jail, designed by local architect Frederick J. Osterling, were completed. A new wing was added and another extended, and the wall around the cell blocks was reshaped to enclose additional area.41 Some injury was done to the Courthouse by the lowering (1913) and widening (1927) of Grant Street, but for the most part the exteriors of the buildings remain as Richardson had intended. The interiors have not been as fortunate. In the 1970s the ceiling heights of some of the courtrooms were cut in half, to make room for mechanical equipment. Luckily, many of these rooms have since been restored. As early as the 1920s, the Jail began to show signs of obsolescence, and in 1924 a county planning commission recommended demolition. Opposition by local architects prevented the execution of this plan. It was the first of many such reprieves the building would be granted over the next fifty years. In 1973 both the Courthouse and Jail were added to the National Register of Historic Places; three years later they were elevated to the status of Historic Landmarks. Such official recognition dampened the zeal that periodically seized cost-cutting bureaucrats and muckraking journalists to alter or abandon them. New facilities have finally replaced the Jail, but fortunately it has been recycled into the new home of the Family and Children’s division of the county court system. This reuse required the removal of all but a few jail cells (kept for display); spatially, the building has been left intact.42

The first thing a visitor to the City-County Building is likely to notice today is how poorly maintained it is compared to the corporate towers around it.43 A patina of cigar smoke seems to cling to the marble of the great hall, and cigarette butts collect in the loggia. But no radical changes have been made to the building. This is a testimony to the longevity of Hornbostel’s vision since, unlike the Courthouse and Jail, City-County has attracted no legion of defenders to protect it. It is hard to say whether the building would be more widely known had it not been built in the shadow of the giant next door. As it stands, the City-County Building, together with the countless “background buildings” that are its peers, offers to architects and historians a cautionary tale. The spotlight of canonization is an unsubtle instrument. Like any useful abstraction, it can encourage a kind of intellectual laziness. There will always be, quoting Ochsner again, “an inherent tension between the desire to create a structured framework” of “known conclusions” and the wish to acknowledge “the more complex and even diffuse context” that is the entire field of architectural production. Reconsidering the canon is an exercise we should periodically undertake. To do so, however, requires not only that we question what is included in the canon, but also that we do some poking around in its shadows.

Acknowledgements

My sincere appreciation to the following persons, whose help while researching this article was indispensable: Pittsburgh architects James Radock and Anthony Lucarelli; Bruce Padolf, architect for the City of Pittsburgh Department of Engineering and Construction; Sam Taylor, architect for Allegheny County; Walter Kidney of the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation; Martin Aurand, Archivist of the Hunt Library Henry Hornbostel Collection, Carnegie Mellon University; and most important, the architectural historian Charles Rosenblum.

Daniel Willis is associate professor of architecture at Pennsylvania State University and the author of The Emerald City and Other Essays on the Architectural Imagination.