Dialectical Utopias

I am interested in the architecture of desire—in the multitudinous ways in which human beings, given the opportunity, always build their dreams, and in the extent to which every building is a little utopia and every modern city a republic of little utopias. In these remarks, I would like to discuss two cities in which a single dream predominates—two of the most successful desert enterprises since Persepolis—at once resorts and last resorts: Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Las Vegas, Nevada. I have chosen to call them “dialectical utopias,” although they could just as easily be characterized as “complementary utopias,” or even “contrapositive utopias.” “Dialectical utopias” is probably best, however, since the cities do speak to one another—although neither of them listens.

On Sante Fe and Las Vegas

At the turn of this century, Santa Fe and Las Vegas were virtually indistinguishable environments. From the late 1800s through the early 1900s, both towns were Victorian Protestant clapboard environments, a mix of colonial and indigenous cultures. Eventually both these Victorian cities were torn down, and the native cultures overridden by intellectual iconographies. Today, the two cities are bound together by the fact that both are invented communities, although we do find, in their historical precedents, manifestations of their contemporary iconography. From the beginning, Santa Fe has been a trailhead and a seat of government, and it has contributed to the administration of those two most interior of human social activities, mining and religion. Las Vegas, on the other hand, has always been a whistle stop. Like most Western cities, it has participated in the economics of mining and religion, since it has served as a refuge from borax mining on the one hand and from the Mormon Church on the other. One might say that Las Vegas has traditionally provided a way to “unredeem” mining and religion through gambling and prostitution.

Both cities are as much ideas as locations, then, and each has been invested with its iconography, conceptualized and ideologized by creative visionaries. In the case of Santa Fe, these visionaries include General Lew Wallace, the governor of New Mexico and the author of Ben Hur, who tried, unsuccessfully, to pardon Billy the Kid, and Willa Cather, whose book, Death Comes to the Archbishop, inspired and attracted another creator of Santa Fe, Mabel Dodge Luhan, the patron who brought the cult of Modernist art to the city. Carl Jung found in Santa Fe and its pueblos a perfect example of everything he wanted to find there. D.H. Lawrence found the same things Jung found and wrote better books about them. Georgia O’Keefe painted the pictures of what Jung and Lawrence found.

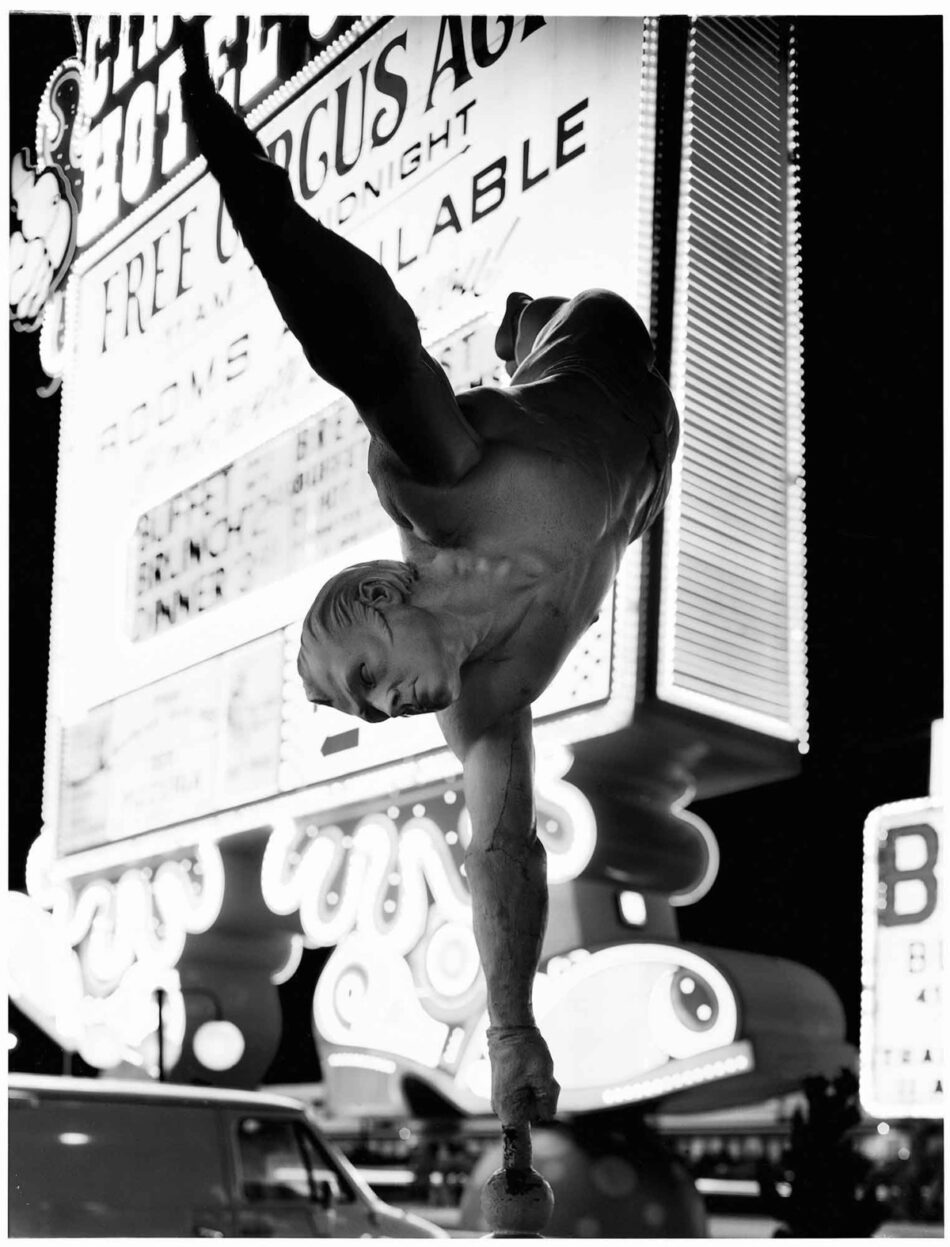

Las Vegas has its own hierarchy of visionaries, beginning with the gangster Bugsy Siegel, who in the 1940s invented the Strip as an oasis, a refuge for contingency and embodied desire, for iconography and idolatry in the Protestant West. Soon after there came Howard Hughes, Orson Welles, Frank Sinatra, B.B. King, and Liberace, all residents at one time or another. Then, in the early 1960s, Vegas’s status as the American Lourdes of Chance was confirmed by a visit from its spiritual father, Marcel Duchamp.

In its transformation into a tourist destination, Santa Fe’s indigenous iconography was adapted to Modernism’s religion of natural materials, cosmic sublimity, and Jungian primitivism—all built over a real desert. Its ideology was probably expressed best by Kasimir Malevich in his essay “Suprematism” (1927), in which he wrote, “The ascent to the heights of Non-Objective art is arduous and painful, but is rewarding nevertheless. The familiar begins to recede into the background. The contours of the objective world fade more and more, step by step until finally the world, everything on which we have lived, becomes lost to sight. No more likeness or reality, no idealistic images, nothing but a desert. I was fearful of leaving the ordinary world of will and idea, but the promise of liberation drew me onward, onto a desert filled with the spirit of Non-Objective sensation, where nothing is real except the feeling.”

This is more or less what Jung, Lawrence, and O’Keefe felt about the place, and Santa Fe has flourished ever since as a kind of naturalized allegory of Modernist values. The iconography in Vegas, in contrast, is about the validation and celebration of secular ambition. (What else is Caesar’s Palace but a historical etiology of the Mafia?) So Vegas speaks the language of worldly empires, while Santa Fe speaks the language of cosmic sublimity; these differences wouldn’t be nearly so interesting, however, if their similarities were not so intriguing. To begin: they are both high desert cities to which one ascends. To reach Santa Fe, the city of faith, one ascends from the dingy mining town of Albuquerque through benign, picturesque foothills. To get to Vegas, one ascends from Los Angeles, the City of Angels, to the bleak unredeemed Hell of the Nevada desert.

The built environment in both cities is desert architecture, its exterior surfaces by necessity hard and reflective. The hard, reflective surfaces of Santa Fe are those plain, solid volumes that connote strength and virtue in the iconography of Modernism. Their monochromatic surfaces signify the oneness of everything (as it always does in the language of the sublime, as it does in the paintings of Franz Kline and Ad Reinhardt). Here too we find the suppression of language and iconography functioning as a Modernist icon of deferred spiritual reward, whose plangent interiority is embodied in the cozy, tomblike rooms of these blank edifices.

The ornate reflective surfaces of Las Vegas, by contrast, do not so much enclose space as shelter it, without signifying any form of interiority. Rather than privileging the space behind the surface, these hard surfaces privilege the space before it, so outside and inside flow together, both adorned by ornamental surfaces that provide the immediate secular reward of bodily rhetorical effect. These surfaces celebrate their difference from everything around them rather than their oneness with the world—and celebrate our difference as well, with no implication of hierarchy. Thus in Santa Fe we are all one in our elevated specialness. In Vegas we are different but equal.

These reflexive characterizations, of course, are about architectural “special effects.” Like all resort architecture, the built environment in both cities is essentially diversionary, although each environment aspires to its own form of disorientation. Simply put: to be in Santa Fe or Las Vegas is to feel lost. First, you are lost in time, lost from history. In Santa Fe you’re lost in perpetual quaintness, perpetual oldness; even its newest buildings look antique, and this oldness is legislated. In Vegas, you’re adrift in perpetual newness. Everything is perpetually being renewed; all local institutions—the casinos, the unions, the government—are in a state of perpetual renovation. Had you seen the explosion of The Dunes, you would understand that the sheer joy and true rapacity with which the past is destroyed in Las Vegas is easily equivalent to the earnestness with which that past is preserved in Santa Fe.

Such temporal disorientation is reinforced by the disorienting function of language in these environments. In Santa Fe, of course, language and signage are simply suppressed; you’re always lost because everything looks the same, and nothing has a sign on it: you’re disoriented in the oneness and sublimity of the eternal West. In Vegas,everything is signed and new, but the signage is about dislocation, about relocating you in some imperial historical instant. Thus, rather than looking the same from every angle, as Santa Fe does, Las Vegas always looks different. In both places you’re disoriented, as you should be on vacation.

The interior spaces of Las Vegas and Santa Fe, like those of all desert architecture, are arboreal: they evoke the lost forest environment that the desert has taken away. In Santa Fe, the interior arboreal space mimics the bower, the nest, or the redoubt; the walls shut out the lateral world. In Vegas the long, low spaces of casinos are the arboreal forest disappearing in every direction; in Las Vegas the walls don’t shut out the world; the ceiling shelters us from the sky—and also, I would suggest, from God and eternity. There is one particular dice table at the Mirage, in fact, that actually has three visible roofs: a long tiki roof covering the entire area, a smaller tiki roof over the dice tables and an even smaller roof above the table itself; above these roofs, of course, is the hotel itself. All these protect us from the vault of the sky, but there is not a wall in sight, only the forest disappearing in the crepuscular distance.

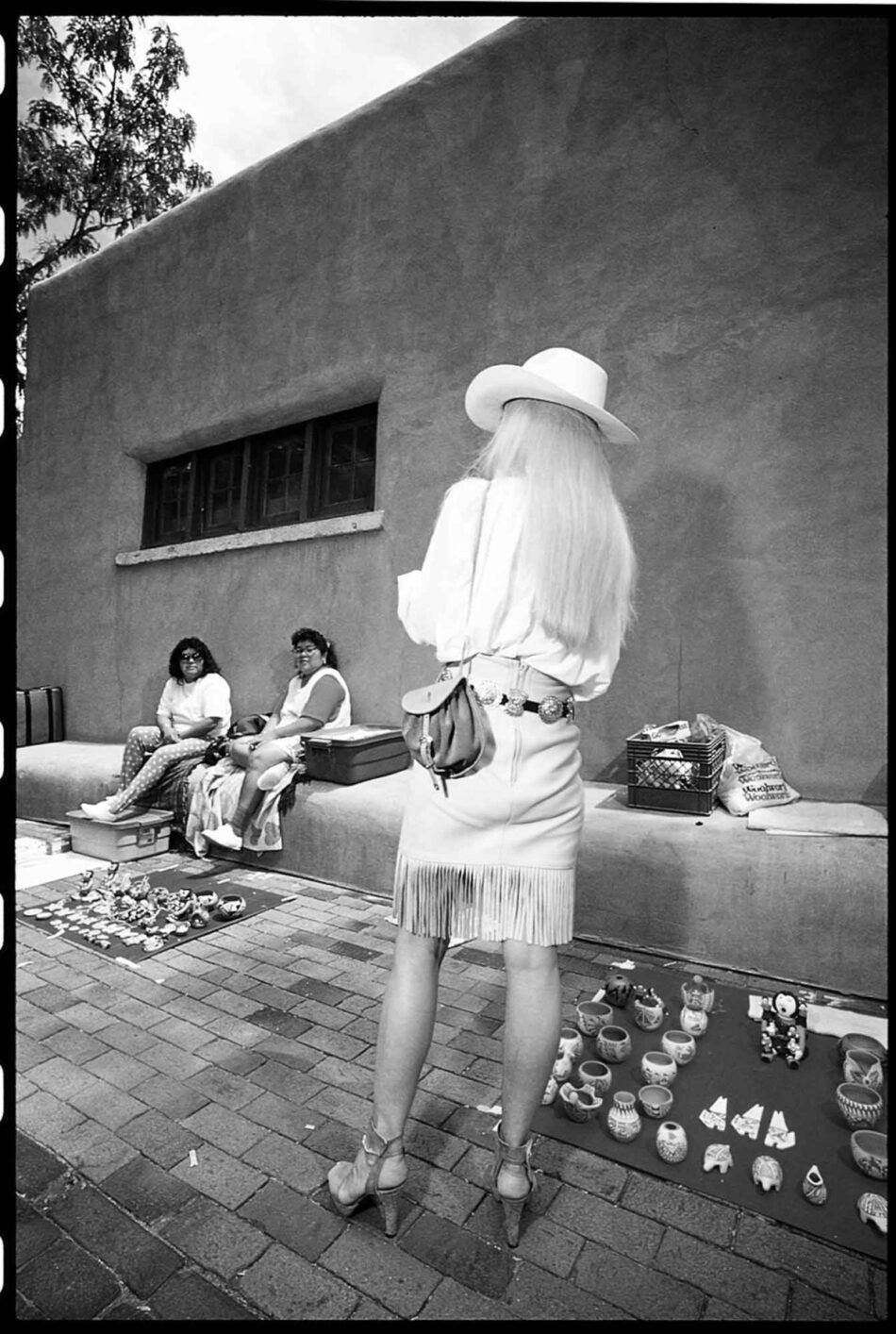

So the issue, again, has to do with two ways of living in the desert—with the question of whether one is keeping out invaders, in the lateral flow of time, or whether one is rescuing oneself from the eternal all-seeing panopticon of the sky. This raises an interesting point about Vegas, since you are always under surveillance in Vegas by the cameras that overlook the gambling areas. What is being surveilled, however, is the body and not the soul. Unlike surveillance in the rest of America, surveillance in Vegas is in the interest of ethics, not morality. It regulates cheating but not the idea of cheating, since by definition gambling is cheating probability. Santa Fe, on the other hand, is a fortress against time and contingency; its oneness enforces the rigorous standards of taste, dress, and behavior that are ritually enacted there; it also privileges the perpetual complaints of its inhabitants about the vulgar changes that seem almost daily to pollute its perfection.

Unlike most of America, then, Santa Fe and Vegas are consistent architectural environments. In most American cities, “high architecture” functions as an intellectual repudiation of the vernacular. In Santa Fe and Las Vegas, the “serious” and vernacular architectures are coextensive. In Santa Fe, the high architecture is legislated; its “serious” buildings, in the best Modernist tradition, are simplifications of its vernacular buildings, whereas in Las Vegas the self-conscious buildings are elaborations and recombinations of the vernacular—selections from the eclectic palette of pre-Modernist American architecture. So it’s easy to see Caesar’s Palace as the combination of a neoclassic building and a filling station or to see the Mirage as a building Albert Speer might have built for the king of Tonga or the fraternity of Freemasons.

Thus we may identify two distinct iconographies: in Santa Fe, the iconography of taste; in Vegas, the iconography of desire. The iconography of taste is a signifier of the absence of desire, since one cannot exercise one’s taste when driven by appetite. Hunger must be satiated before one can select the perfect morsel. The high rituals of Santa Fe involve demonstrating one’s theatrical lack of lack—one’s transcendence of need and desire and ascendance into the realm of taste. Vegas, on the other hand, rather straightforwardly embraces the iconography of desire.

Consider the contrasting styles of shopping. Shopping in Santa Fe is slow; its pace is geological. The potential buyer is concerned with the authenticity of the object, its source and chaste appeal; in the case of native handicrafts, the buyer is even concerned with the blood, the genealogy, of the author, with his or her antique authenticity. Shopping in Vegas is quick. It is about spectacle, not scrutiny; about our desire, not the object’s “virtue.” So we respond not to the authenticity of the object, but to its persuasiveness, to the ornament, the rhetoric of the design. We do not care who made the things we buy in Las Vegas; we luxuriate in the privilege of not caring.

Let me tell you a story. I recently went to Santa Fe to give a lecture. On the morning after my talk, my wife and I strolled downtown to a little place where one can buy croissants and cappuccino. To get this croissant and this cappuccino, you stand in a line of dentists—a filling of dentists, an agony of dentists… whatever. When you achieve the counter, you order your coffee and are issued a number. Then you seat yourself outside upon an unstable raffia chair at a wobbly table. There you may enjoy the light and space so beloved by northern European architects, while an aged Navajo crone operates a giant espresso machine. When she has operated the giant espresso machine to her satisfaction, she passes the tiny cup to an indolent low rider who strolls over and deposits it on your table, avec croissant.

So, I am sitting there waiting, feeling a little embarrassed about enlisting someone older than my grandmother to score my caffeine. I’m also a little annoyed because I’ve been sitting there for thirty minutes waiting for my coffee. And it suddenly occurs to me that I am thinking “Las Vegas.” I’m expecting comfort and efficiency; I’m getting leisure and authenticity. The people around me, I realize, have come to Santa Fe to waste time, whereas people go to Las Vegas to waste money. So I’m sitting there wasting my time, which I value, when I could have been in Vegas wasting money, which I don’t.

Eventually the low rider arrives with our coffee, and noticing my casino jacket, he says, “Hey, you been to Vegas?” I admit to living there and he says, “Boy, it’s great! My wife and I go there every year.” I ask him why, and he says, “Oh, we like it. They treat you nice.” “Do you gamble?” I ask, and he says, “Well, you know, I don’t gamble and never plan to gamble. But the first time I went there, we had a nice room; they were nice to my kids; they were nice to my wife. And as I was walking out of the casino I said, ‘What the hell? I think I’ll gamble.’ And I gambled, and I lost, but I didn’t care. Then I came home and I could stand all of these dentists.”

What the low rider was describing, I would suggest, is a distinction that Jane Jacobs makes in Systems of Survival—she describes the differences between elite leisure cultures and commercial comfort cultures. Elite leisure cultures are composed of practitioners who must work sporadically and with great intensity in jobs that require extensive educational indoctrination and elaborate initiation rituals, each of which imbues the practitioner with a sense of class responsibilities. Such practitioners include hunters, surgeons, dentists, lawyers, professors, and soldiers. What this sporadic activity gives these people, Jacobs suggests, is not so much money as time, vast hours of leisure that class tradition dictates should be “well spent.”

Jacobs opposes this leisure culture to a commercial culture that values comfort and convenience, inhabited by people who, because they work in the commercial world, must work all the time and engage in perpetual, on-the-spot innovation. Where the successful inhabitants of leisure cultures gain time and status, the successful inhabitants of commercial cultures gain money and mobility.

Thus the perpetual conflict between democracy’s hierarchical elites and its commercial culture is sorted out in Santa Fe and Las Vegas. In Santa Fe, one may exercise one’s hierarchical, elitist preferences without the confusions of commercial democracy; in Las Vegas, one may experience the risk, spectacle, comfort, and convenience of commercial life without the burden of “eternal values” or wasted time. Where else in America but Santa Fe could a member of the professional elite stand before a member of another culture who kneels behind a blanket of trinkets, and, like some 18th-century Neapolitan nabob, patiently select the perfect authentic object from those on display? Where else in America but Las Vegas could a hardware salesman from Indiana bet his year’s earnings on a turn of the card and then spend his winnings on a lamé sport coat? These are the two sides of the American urban coin—each pure and unadulterated by the other—each a little shocking in the glamour of its permissiveness. Dialectical utopias.

So I am talking about resorts, about cities that market themselves as the heart’s destination. Since such discussions constitute the dream work of cultural criticism, I shall try to ground my observations, as much as possible, in my own waking experience of these places. I should probably try to suppress my own utopian expectations, as well, but there is no denying that I live in Las Vegas, and have chosen to live there, when I could just as easily reside in Santa Fe. So let me confess at the outset to my preference for the real fakery of Las Vegas over the fake reality of Santa Fe—for the genuine rhinestone over the imitation pearl.

As Jean Baudrillard has remarked, Las Vegas is a theme park, like Disneyland, except for the fact that people live in Las Vegas. The same, I should note, can be said of Washington, D.C. or 5th-century Athens or Imperial Rome—or Santa Fe. What interests me about Las Vegas and Santa Fe, specifically, is that they present themselves as choices—as dreams within the dream. Santa Fe is older and was invented as a tourist destination by the railroad, while Vegas was invented by the highway and the mob, but they are both theme parks, conceived and constructed as such, each grounded in a distinct mythology of the Great American Desert.

These two mythologies are so distinct, in fact, that, if you combined Las Vegas and Santa Fe, you would have an ordinary city of the American West, like Phoenix or Los Angeles, with intensified iconography, but with very little redundancy—since, in a very real sense, Las Vegas and Santa Fe are refuges from one another. So, in this new, combined city, Santa Fe would provide the upper crust, the guardian liberal establishment and the indigenous lower depths—the white top and the brown bottom, if you will—while Vegas would provide the green middle—the vast mercantile center of American society.

To draw the distinction more sharply, we might say that Santa Fe is a resort that attempts to embody and evoke the eternal West—a Shangri-La where time doesn’t move—a fortress and a refuge from history, a purified environment that embodies the values of a peculiarly American brand of parental modernism. Thus Santa Fe has become a theme park for America’s professional classes—there dentists and lawyers ride in Broncos, not on them. On this site, the hierarchical status quo is naturalized into an etiology of spiritual elitism.

Las Vegas, on the other hand, is a resort that seeks to recall the frontier West—an egalitarian boomtown in a Biblical wilderness of fallen nature. It is a nonstop, round-the-clock saturnalia, an American fantasy of slaves in the role of masters, providing its customers with a slave’s idea of a master’s life—which is, of course, a hell of a lot more fun than the master’s actual life, since the masters of this culture are necessarily burdened with puritanical noblesse oblige. So Vegas is an institutionalized social revolution. Its emblem is the wheel—not the normative wheel implied by the Modernist “cycles of nature” but the Wheel of Fortune. This emblem of postmodern contingency presides over a denaturalized marketplace that becomes its own commodity—that regales the American commercial classes with an iconography of secular ambition.

Dave Hickey is an art critic. Air Guitar, a collection of his essays, was published recently by Art Issues Press. The essay above was originally presented as a paper at a GSD conference “Denaturalized Urbanity,” organized by Mohsen Mostafavi, formerly a member of the architecture department faculty.