Cappuccino Urbanism, and Beyond

Of course I could be wrong and aggrandizing, but it seems to me that the section of this issue on contemporary urban design could produce or at least mark a turning point in the discipline. The radical critique of current American practice articulated here seems as potent and important as the radical critique of Modernist practice articulated and worked through from the early 1960s (with Jane Jacobs) through the early 1980s (with Postmodernism). This time it is a radical critique of the late and stale fruits of that earlier critique. Just as late Modernism calcified into dogmatism and second rate production—inhuman corporate and public housing towers, so too has the humanist reaction against Modernism devolved into lifelessness and shallow formula. This devolution and the resulting need for a radical change of direction is here expressed with the power of a long submerged awareness at last coming to the surface.

The realization in these pages is that our hope for revitalized urbanism and a more fulfilling and meaningful city life through a return to the patterns, texture, look, and scale of certain pre-20th-century cities has created innumerable delusions and falsities. One can create small-scale urban zones that combine places to live, work, shop, dine, and play, zones that make being on streets appealing again, that are softer, safer, and prettier, but these zones will merely put an old dress on social, psychological, cultural, economic, and political realities that are as new as each new day.

To be more specific: in most revitalized or new American urban nodes (e.g., “lifestyle centers”), one can shop in stores with good and interesting merchandise, enjoy a sophisticated meal, find amusements like movies, stroll outdoors in clean and tastefully decorated parks and streets, and end up comfortable and content under a street tree sipping cappuccino. And this is certainly a big step up from being surrounded by cars, street-level blank walls, surface parking lots, huge empty plazas, and office towers. But do the comfortable passive pleasures of cappuccino urbanism suggest anything but a tiny portion of a life well lived?

Because Michael Sorkin addresses this question with extraordinary care, thoughtfulness, historical perspective, and passion, his essay begins the issue. He confronts an urbanism that glorifies yuppie lifestyles with awareness of our world’s most disturbing realties: the huge and growing gap between the rich few and the many poor, current and impending ecological and climatological disasters, and the fundamental cruelties and injustices so relentlessly present to us in wars and genocide. He does not suggest that urban design can provide solutions, only that urban design that actively insulates us from these realities is morally bankrupt—that true urbanism by definition embraces human diversity of all kinds.

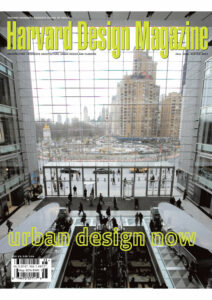

The sharp analysis of urban design by several other critic-scholars here helps enrich and elaborate the complex and diverse realities of the contemporary: the spectacular elephantine urbanism of Dubai and Pudong; the heartening successes of several new European public spaces; the increasing time spent in “virtual space” because of the Internet and iPods; the growing importance of large interior spaces like malls and museums; the effects of planners and developers on urban design and urbanity; the achievements and regressions of New Urbanism; urbanization of suburbs and suburbanization of cities; the evolution of cities into regional metropolises; the effects of immigration; urban design as “large architecture” and as landscape architecture; increasing American social diversity; designing for spontaneity and unpredictability; and so on.

The questions that framed the discussion in this issue were:

1) What are examples of highly successful (or instructively unsuccessful) urban design projects of the past decade?

2) Given urban dispersion, democratized decision-making, the dominance of private development, the reactive or ad hoc nature of contemporary planning, and the absence of a broadly shared view about what constitutes good urbanism, is urban design is still possible?

3) What are the opportunities, if any, for inspired urban design intervention? Who are current most likely clients for urban design?

4) Is urban design really more about establishing guidelines and regulations and therefore not about design in its common meaning? Can design guidelines and regulations be a means if achieving good urbanism?

5) Is urban design predominately a small-scale activity—work with places and neighborhoods—not a bold, large-scale transformative activity?

6) Does the metropolis of dispersed nodes (like Phoenix) require surrendering the wish for a civic center?

7) What are the strengths and limitations of “mainstream” urban design in America?

As always, we hope to hear your responses to all this.

Addendum by Alex Krieger

Aristotle expressed a lower tolerance for those whom he called “cityless.” Could he have imagined a world in which half, and soon more, of humanity would no longer be without cities? And would he have presumed that a model of a particular kind of city (Athens, say) that dominated in his own time could fulfill the needs of three billion urban dwellers? The challenge for urban design in its second half-century, as the authors in this issue recognize, is not to establish a canon for the discipline based on a particular idea about what a city ought to be. It is to come to terms intellectually with the diversity of urban dwellers’ needs and desires: to develop a sophisticated awareness of the environment and one’s impact upon it; to be more civil and responsive towards others; to not simply express concern for those less fortunate but to act on their behalf; to use technological advances for more equitable distribution of resources, not only for increasing personal wealth; and to tolerate less waste and redundancy. Different “urbanisms” should flourish in a still urbanizing world, including places where cappuccino may be happily consumed.