Soft Architecture

I experience a slight to moderate sense of alarm when the phrase “family planning” is mentioned.

Family planning sounds like … taking the fun out of sex. Planning. Not hot. High school sex-ed classes. “Do you have a condom?” A late period. Stress. Republicans rolling back abortion rights. Ugh. False alarm. Relief!

If, like me, you’re a heterosexual woman in your 30s and you hear “family planning,” it gets worse. Anxiety.

Should I have kids? How many? Does he want to have kids? And when will it be too late to have another? Can we afford two? Do I have the stamina to nurse a child for a year and a half (pumping, pumping, pumping)? Will I be able to maintain my career? Will my partner be sexist when it comes to the needs of a small child and the associated housekeeping? What kind of world will we be bringing a child into? Aren’t there too many children in this world already? Will I become a slave to motherhood? How will I rear a child (in a decent school district!) given New York City’s “sky’s the limit” real estate market?!

Men may be asking themselves some of these questions. But not all of them. Family planning for a man involves other apprehensions, and especially this one: “Can I get it up?”

In 1969 the architect Mark Mills completed a single-family home (begun in 1960) for June Foster Hass, a sculptor recently widowed at the time of the commission. The residence perches on a rugged cliff overlooking Yankee Point in Carmel, California. The dramatic sunken lounge with picture windows faces a spectacular view of a tide pool and the ocean beyond, the cylindrical room literally draping over the crags of the hillside. The cruciform structure includes three low-slung groin-vault window bays facing the water, while the home’s longer axis extends perpendicularly away from the Pacific. The house hugs the cliff tightly, never reaching a height of more than 14 feet above grade.

On numerous occasions Mills referred to the project as the Limp Penis House. Limp penis. Let that sink in a sec. Not words previously combined in the history of architecture, to my knowledge.

The lounge in particular does look quite flaccid, drooping over the bluffs. It even has a foreskin-like hood over its bay window, which, in exterior shots, reveals the interior orifice of the room to be a urethra-like channel of the home’s longer axis. In plan, the entry of the home tucks visitors behind what seems like a testicle. Though the lounge appears to be the limp penis in question, the plan shows the longer axis that terminates in the study, the room farthest from the ocean and the lounge, itself seeming quite penile, with a little pouch at the end of its sheath like a condom tip. So the Limp Penis House may have two penises, one evident in plan (emerging from the driveway, ending in the study) and one in elevation (the lounge’s front appendage, lying over the cliff).

Skyscrapers are from Mars; amphitheaters (or is it tunnels?) are from Venus. Erect structures are phallic and penetrative, and cavernous containers are womb-like and receptive … blah, blah, blah.

Is it cruel to design a saggy penis house for a widow? Better questions might be, why construct a biomorphic structure mimicking human genitalia? What does it mean to occupy a building designed on the morphology of reproductive organs?

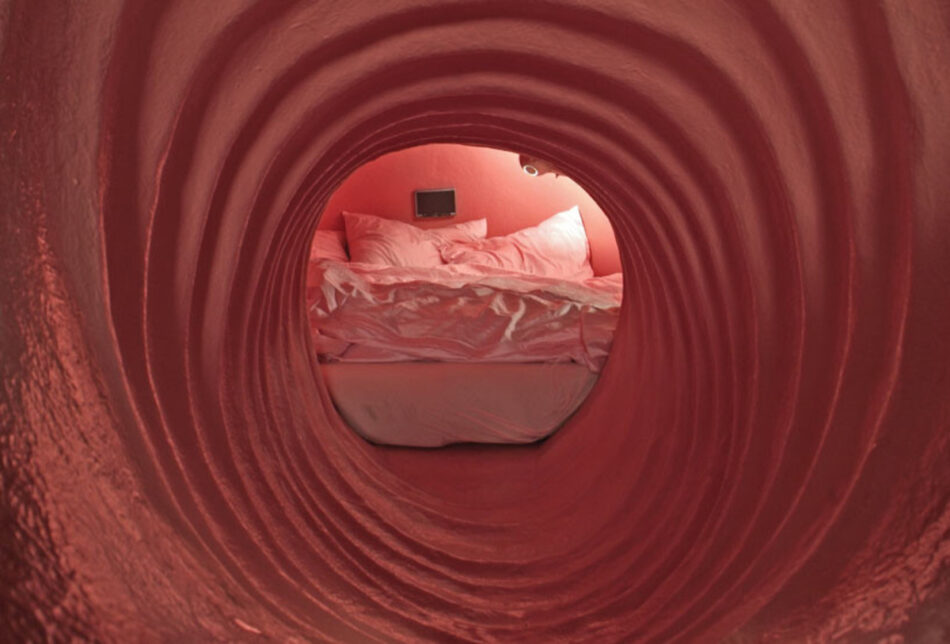

Friedrich Kiesler’s ovoid-like Endless House (1947–1960) was intended to be a kind of adaptable microcosm of human development based on the metaphor of the womb. As the artist Jean Arp wrote of Kiesler’s project, “in these spheroid, egg-shaped structures, a human being can now take shelter and live as in his mother’s womb.” A more recent version of womb literalism is Atelier Van Lieshout’s Wombhouse (2004), a proposed extension to a retired male gynecologist’s existing home. As Joep van Lieshout notes, the uterus in fetal gestation “is not only every human being’s first dwelling, but also the only human body part that can be inhabited by another individual”—the only organ that ever functions as human shelter and is therefore emblematic of the nurturing, protective environment that architecture can provide. His structure looks like an enlarged medical model of female reproductive organs, featuring a vaginal canal entryway that takes you to a bedroom uterus, and fallopian tubes that connect to a small bar and bathroom in the ovaries.

The implication of a house design that jokingly refers to an unerect penis is quite different than those inspired by the uterus. Skyscrapers can be envisioned as erect structures teeming with inhabitants, sperm-like masses stored in cellular compartments, busying themselves with whatever corporate tasks they do all day. In contrast, Mills’s Hass House is a squat, curvilinear residential structure designed to integrate itself with the cliff. It interpenetrates, one might say, the human-made with nature, rather than thrusting itself vertically into its surroundings. The Hass House refuses to “get hard.” It is not in a procreative relationship to its environment—human procreation being a form of domination, of Homo sapiens’ DNA imposing itself on the universe.

Then again, most of the time penises are not hard.

There is something deflating about unveiling the phallus, culturally imagined in a patriarchy to be perpetually in its virile, priapic hard-cock state, to be a limp penis. That, a wilted little worm, that is the foundation of eons of male power? In a video accompanying the 2012 real estate listing for the Hass House, the agent repeatedly refers to the shell-like qualities of the house; the architect’s comparison of the structure to a limp penis may not be the best selling point. I, however, am charmed.

So much anxiety about getting it up. Viagra. Penis pumps.

I love that Mills’s design admits that sometimes the dick is just limp. Not everything is about sex and procreation. However great women’s anxieties about the vulnerability of family planning to biological imperatives, for men the impotent penis is undoubtedly a big bummer. Mills’s sort of architectural biomorphism allows for a zone of receptivity that in some ways hearkens to the oceanic plenitude of the womb as Kiesler and Van Lieshout imagined it for the fetus. But you don’t need to go back to the uterus to experience it. You can dangle a limp penis at a tide pool instead.

Eva Díaz teaches at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Her book, The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College, was released in 2015.