Living Pasts and Feedback Loops in Cape Town

The optimism of the architectural plan is a mutable ideal: in the real, built things are subject to varying degrees of tinkering, fine-tuning, modification, and even remodeling. There is a euphemism to describe this inelegant process: adaptation. Heinrich Wolff—a South African architect whose eponymous Cape Town studio, Wolff Architects, has developed an experimental approach to educational buildings—has no qualms using the word. “We don’t subscribe to a version of architecture that each building is an intact masterpiece that can’t be touched,” he told me during a visit to his small studio, which he directs with his wife, Ilze, an architect interested in historical research and creative activism.1 “Rather,” continued Heinrich, “we believe in the idea of open frameworks that don’t resist adaptation.” His statement prefaced a straightforward account of the disjuncture between plan and site at the first high school he designed.

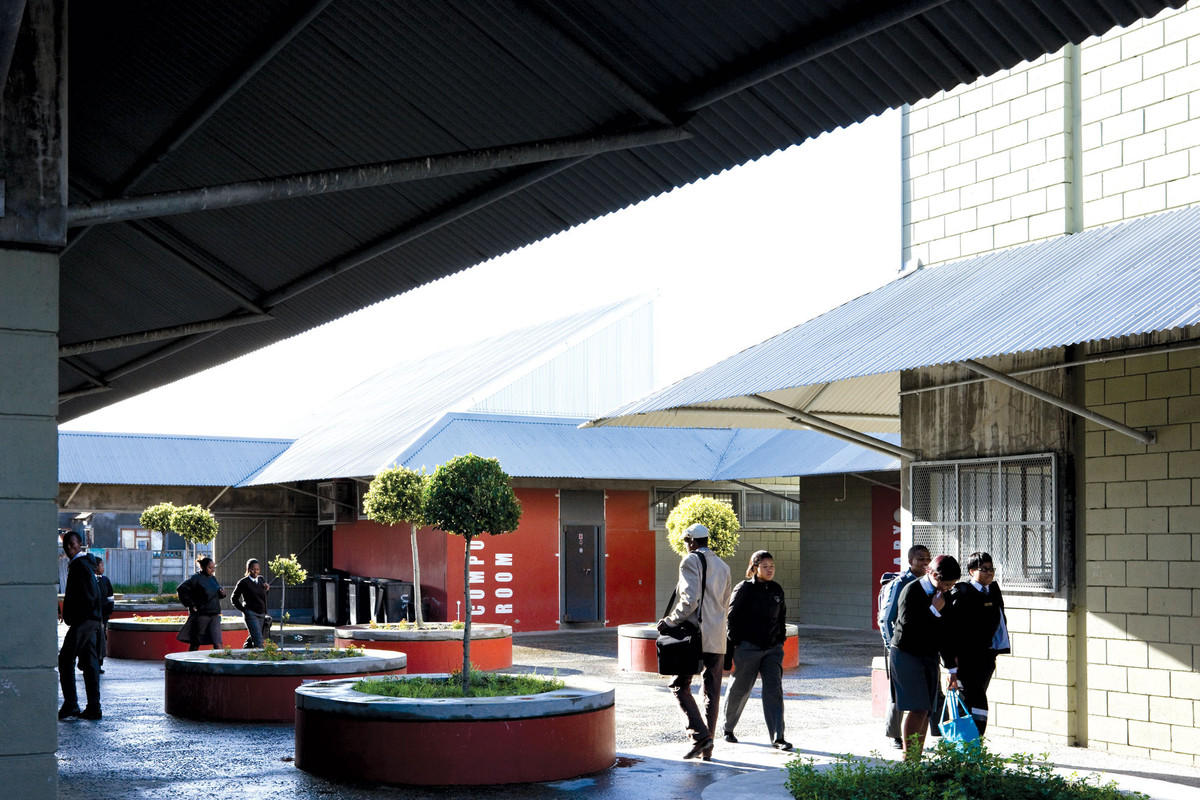

Usasazo Secondary School is located on the windswept flats at the southeastern edge of Cape Town’s metropolitan area. Formerly known as Maitland High, the rechristened high school opened at its current address in 2004, 10 years after Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) came to power with promises of an extensive school-building program and a rollout of electricity to 19,000 segregated black schools cruelly left off the grid by apartheid-era planners. Usasazo—whose name means “dispersal” or “scattering” in the Xhosa language of Mandela, speaking to the historical forces that shaped Cape Town’s atomized and still-segregated urban form—is emblematic of a promise kept. That promise is worth revisiting in granular detail as it says something about the country’s democratic impasse, a subject of increasing pushback by young South Africans.

Shortly after contractors moved out of Usasazo, teachers and administrators started fiddling with the school’s design. For the most part, their interventions were supplementary and reflected the hardships of living and working in Khayelitsha, a sprawling residential area (or “township”) with a majority black population confronted by large-scale unemployment and slum-like living conditions. The most immediate change involved chaining up re escapes to prevent illegal access at night. Two vault doors were ordered, one for the computer lab, another for a tech lab created from one of the school’s 37 classrooms. Extra security frills were also added to existing burglar-proofing measures. But for the bathrooms, which stopped working soon after opening due to poor sanitation infrastructure in the neighborhood, the new school was now fit for purpose. The bathrooms, which were designed to offer limited privacy due to the prevalence of drug dealing, key into the complexities of another post-apartheid guarantee.

All South Africans, promised the ANC in 1994, would enjoy “an improved standard of living and quality of life.”2 Dysfunctional bathrooms and sanitation systems, like the so-called mud schools in rural parts of the country, speak to a frayed promise. In 2010, a public inquiry found that Cape Town’s metropolitan government had violated the human rights of Khayelitsha’s residents by installing toilets without enclosures. Five years on, Chumani Maxwele, a student at the University of Cape Town (UCT), unwittingly sparked a social revolution when he scooped feces from one of Khayelitsha’s hated portable toilets and flung it onto a 1934 statue of industrialist and colonial politician Cecil John Rhodes. His action spawned a hashtag movement, #RhodesMustFall, which yielded a new noun, “fallism.” Following the statue’s removal from UCT’s campus, disaffected fallists—students hip to Afro-Caribbean philosopher Frantz Fanon and intersectional theory—started using a new hashtag, #FeesMustFall. It resonated nationally. University students, some graduates of schools like Usasazo, began calling for a free, equitable, and decolonized tertiary education.

The running battles with police that followed in 2016 prompted comparisons to Paris and Tokyo in 1968. There was, however, a better local precedent: the 1976 high-school rebellion, which started in Soweto, a black dormitory suburb of Johannesburg, but quickly spread nationally. Xolile Mosie, a 17-year-old student at Langa High, Cape Town’s oldest black township school built in 1937, became one of the first Capetonians killed by police in that rebellion. This history might seem remote from the practicalities of designing educational infrastructure in contemporary South Africa, but for the Wolffs it is proximate and real. “The past lives in the present in the most powerful ways,” they wrote in an open letter challenging a 2017 city-government decision confirming the sale of a former whites-only remedial high school in an upscale suburb to a Jewish day school, instead of using the site for much-needed social housing.3

The letter forms part of a long-standing activist agenda within the studio. It is not just ideas of restorative social justice that motivate the Wolffs. As members of Docomomo, an international nonprofit interested in the study, interpretation, and protection of modern architecture, they successfully campaigned to save architect Roelof Uytenbogaardt’s eccentric Werdmuller Centre (1975), a failed mall project, from demolition. “Our activism is deeply embedded in the moment of research,” explained Ilze.4

The evolution of this piece of writing owes to my interest in the Wolffs’ activism, which is long-standing and often at odds with views of the mostly white, male-dominated architectural fraternity. I bumped into Heinrich at a police station one day while verifying some documents. Stocky, blue-eyed, and ebullient, he became animated when our conversation turned to the awkward détente following the 2016 student rebellion. The opinionated middle class, he said, just doesn’t get it—“it” being the source and depth of youth rage. Curious to learn more, I suggested a meeting to review his studio’s educational work. Perhaps, my paraphrased offer went, a review could illuminate an aspect of that rage. Sure, he replied. This, more or less, is how we ended up talking about adaptation.

One adaptation in particular speaks to the mutability of the plan. It is not reflected in photographs on the Wolff Architects website, nor is it discussed in a recent book of global school-construction practices where Usasazo is hailed as a model project. In a preface to her positive review of Usasazo, Claire Kemp, a British architect and coauthor of Building Schools: Key Issues for Contemporary Design (2015), writes: “Through a deep understanding of the wider community in which it is situated school buildings also have the potential to tackle issues in the local community and reinforce the identity of place.”5 She is correct in her appraisal; it’s just that the optimism of the architectural plan, an ideal worth defending, ultimately proved unworkable in Khayelitsha.

Usasazo was Heinrich’s first school project. Aware of the “misanthropic thought,” as he put it, that underpinned the apartheid state’s design and rule of segregated black schools following the promulgation of the 1953 Bantu Education Act, Heinrich tackled the design by asking himself a singular question: “What constitutes a school of the new South Africa?” He gleaned the answer from two sources: Usasazo’s congested urban context and its skills-based curriculum, which included entrepreneurial training in hairdressing, car repair, and food production. Eschewing the stock design of state-owned school buildings, which are typically located at the center of a site and enveloped by fences, green turf, and parking lots, he placed the school on the site’s boundary line. He added hatches with roll-up doors to classrooms on the street edge, thus enabling students involved in vocational training to directly engage with the public.

The industrial form of the hatches was ameliorated by the introduction of canopies and street-side seating, as well as bold graphics painted on the walls. Heinrich describes these additions as “gestures showing generosity toward the public realm.” Students and residents delivered an unanticipated verdict on the porous new building. “Kids would bang on the roll-up doors from outside, even blow smoke in, to antagonize the teachers. This remained a problem for years. We suggested a shutter with acoustic material inside, but they decided to block the entrance up.” Heinrich wasn’t entirely surprised by the decision, but he remains flabbergasted by the removal of the canopies and benches. A structural adaptation quickly turned into a full-scale refutation of civility. “It was absolutely mean”—but also entirely consistent with public life in South Africa, where hard borders and policed thresholds are the norm.

Ilze shares with her husband an interrogative method of going about things. “For me, with each project, it is about finding and understanding the unique question,” she said. Where Heinrich is prone to exuberant metaphor, Ilze, who has an Angela Davis–style Afro and abundant freckles, is more composed. “How do you differentiate between pedagogy and education?” she asked me during our conversation. “In a way, our new democracy demanded a new pedagogy, not just education, which is the facilitation of a set of principles. The buildings that came out of this thinking are not your normal educational buildings; they are trying to facilitate a different way of teaching.” They also promote participatory citizenship.

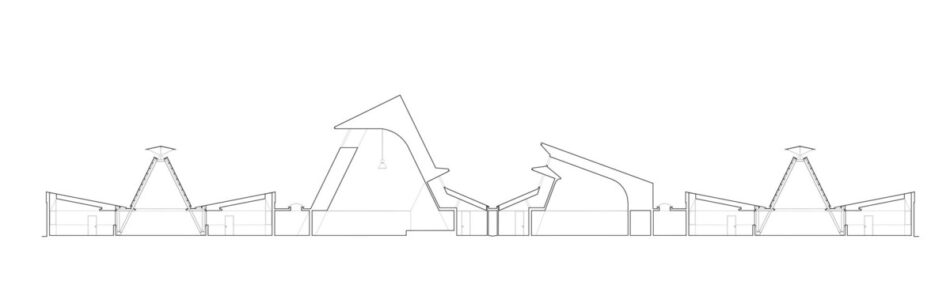

Between working on Usasazo and Inkwenkwezi Secondary School—the studio’s second school project, completed in 2007 on a sloping site adjacent to Dunoon, an informal settlement on the northern periphery of Cape Town—the Wolffs learned that educational buildings in townships often serve as communal buildings. “A school,” expanded Ilze, “is often a rare opportunity to make an urban space encompassing educational and social functions within a neglected social realm.” The vertical rise of the main hall at Inkwenkwezi (“star” in Xhosa) is church-like and projects its presence over the horizontal sprawl of Dunoon’s ephemeral dwellings. Residents have eagerly bought into the symbolism. Some 10 church groups lease space from the school on weekends.

Wolff Architects is currently working on two educational buildings: new premises for a special-needs school focused on children with Down syndrome or autism, and an interdisciplinary arts center in Woodstock, a rapidly gentrifying inner-city neighborhood. Construction on Cheré Botha School, which further expands on themes of collectivism and micro-urbanity in a school environment, is currently in progress. The tentatively named Centre for the Periphery, earmarked for completion in 2019, is a satellite for the Centre for Humanities Research at the University of the Western Cape. The center, which will inhabit a retrofitted former whites-only school built in 1915, will foreground the participatory, artisanal, and often activist cultural practices that grew out of Woodstock. The center, offered Ilze, will expand dialogues around contemporary culture along with initiatives like the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, which opens later this year in a harbor-side retail development.

But why should four diffuse projects, each loosely bound by an educational theme and located in a metropolitan context celebrated globally as a leisure destination, matter? “The thing of building a school in a city is not a straightforward question,” said Heinrich. “It is a highly contested and complicated thing. To create an urbanity that is appropriate to every site and is convincing for people to buy into is a difficult thing to do. That is why we talk about our failures. We are inviting a larger feedback loop.”

Sean O’Toole is an arts journalist and critic based in Cape Town. With Tau Tavengwa, he is the coeditor of the magazine Cityscapes.