Reading Architecture in an Era of Globalization

The architectural profession is in the midst of a long-overdue ethical reckoning. For years, it could ride the tidal wave of globalization to bigger and better commissions while still claiming that it was fighting the good fight. Nowadays, architects are more likely to be on the defensive. Our most celebrated architectural minds are routinely chastised in the media for placing personal vanity above the interests of the general public. And the fact that many of them have been far too willing to brush aside a client’s dubious ethics for the right commission has done little to dispel that perception.

Yet what we often ignore is the striking degree to which architecture’s current dilemma is a reflection of a more radical reorganization of the social fabric under laissez-faire capitalism. As the wave of globalization that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall accelerated, easing the flow of people and capital across national borders and opening up new markets, it created a new type of audience, one made up of global elites who tend to view everything through the lens of the market. At the same time, it threw up new barriers between those same elites and the poor and working masses who make up the majority of the world’s population, and who have been mostly cut off from the benefits of the global economy.

What has been lost in the process is the civic space where meaningful architecture can happen. Instead, architects increasingly seem to be faced with one of two equally dispiriting choices: Either they embrace the current status quo and ally themselves with the world of money and power, or they relegate themselves to working on the margins of the global economy, where, despite often receiving glowing praise from the media, their work will have limited social or cultural impact.

This is not the only time that architects have been forced to confront the limits of their idealism. Following the student protests of May 1968, groups of militant architects in Europe rejected the entire profession as hopelessly beholden to a venal bourgeoisie, choosing instead to work hand in hand with the urban poor to rebuild their communities. Meanwhile, those architects who refused to reject aesthetic issues entirely, preferring to work within the framework of architecture, sought to develop the outlines of an architectural vocabulary that reflected the values of an emergent pop culture, designing interactive cultural facilities, mobile medical stations, and community buildings for the children of the working classes.

Neither approach got much traction. Ignored by the government and distrusted by the working classes they sought to serve, the most militant disappeared into academia or gave up on architecture altogether. Others, like Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, would shift their attention to the cultural sphere, where their ideas were more warmly received. By the late 1970s, a group of architects at London’s Architectural Association, having given up on the idea that architecture could be a vehicle for social change, were positioning themselves not as social reformers but as social critics. Taking their cues from French philosophers such as Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault, they sought to create an architecture that reflected society as it really was, exposing all of its internal contradictions. If architecture couldn’t rid the world of human suffering, they reasoned, it would at least liberate us from various forms of psychological and sexual repression.

That faith survived the 1980s, with the rise of privatization and the backlash against big government. And it would hold true despite building frustration over the increasingly peripheral role that architects played in shaping the kind of large-scale developments that could have a meaningful urban impact. With the tidal wave of globalization that followed China’s embrace of state capitalism in the late 1980s and the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991, new markets were opening up in Europe and in Asia.

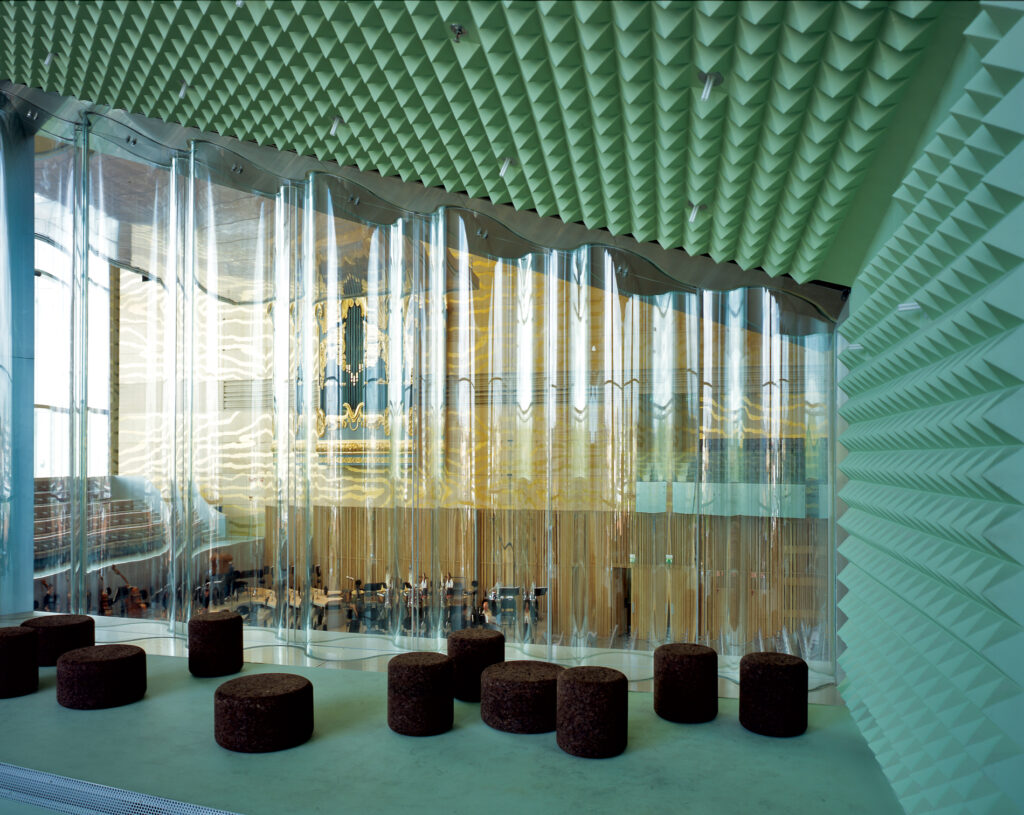

Meanwhile, advances in computer software technologies were creating unexpected formal possibilities, making it easy for architects to buy into a neoliberal fantasy that equated economic liberalism with social, political, and creative freedom. The result, for a time, was a profitable alliance with the cultural world, not only with institutions that were building their “global brands” in the superficial pursuit of tourist dollars, but also with those involved in a more serious effort to establish their presence in the public realm and raise the level of cultural discourse. And the rewards were real: The first few years of the new millennium alone produced some of the most memorable civic architecture of the past half-century, including SANAA’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Hadid’s Phaeno Science Center in Wolfsburg, Rogers’s Barajas Airport Terminal in Madrid, and Koolhaas’s library in Seattle and Casa da Música in Porto.

As the decade wore on, however, the dark side of globalization became harder to ignore. Pundits began worrying about the widening gap between those who profited from the new economy and those who had been left behind, proclaiming the arrival of a new “gilded age.” In 2010, the historian Tony Judt published Ill Fares the Land, his cri de coeur for the social democratic state, mapping out how neoliberal economic policies have hollowed out a middle class that acts as the social glue in a healthy civic society. Four years later, the economist Thomas Piketty published Capital in the Twenty-First Century, in which he speculated that the so-called “golden age” between 1945 and 1973 had been a historical aberration, and that the surge in inequality that had paralleled globalization was most likely permanent. Other scholars were noting the relationship between climate change and a Eurocentric view of modernity that linked social progress with a continual process of growth and development.

Meanwhile, around the very same time, the civic and cultural institutions that had been architecture’s most important patrons for the past decade were being displaced by a new kind of client that was beginning to recognize how “cutting-edge” architecture could imbue their plans with an aura of civic virtue. In the lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, just as the popularity of architects like Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas was cresting, Ian Buruma published an article in the British newspaper the Guardian condemning Koolhaas, Dominique Perrault, and others for taking part in a competition to design the headquarters building for CCTV, the state television company. Buruma’s assertion was that their art was allowing the Chinese Communist Party to project an image of cultural openness even as it cracked down on internal dissent. And it reflected what was becoming a growing (if simplistic) consensus in the West that the high-profile buildings being constructed in Beijing ahead of the Summer Olympics were simply a form of state propaganda.

Soon, similar criticisms were being leveled at projects in the Persian Gulf States, where autocratic governments were recognizing that formally lavish and technologically advanced architecture could serve as a useful tool in promoting a progressive image as they bid to join the expanding global economy. In 2009, for example, Human Rights Watch famously published a report documenting labor abuses on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi, where construction was set to begin on a cluster of cultural buildings that included a Gehry-designed branch of the Guggenheim Museum and a Jean Nouvel–designed branch of the Louvre. The report prompted protests from art world activists, leading Gehry to hire a human rights consultant.

Less commented on, however, was how these projects were used to reinforce a broader and more insidious pattern of class and racial stratification under globalization. Set at a safe distance from the mainland and within easy access to the airport, the museums were the crown jewels of an ersatz world populated by private villas, golf courses, and five-star resorts, where deep-pocketed tourists and wealthy Emiratis could mingle at a safe distance from various “undesirables.” In fact, Saadiyat Island is now being emulated on a much larger scale in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates’s close ally, which has invited an international cast of celebrated architects to take part in the construction of half a dozen new mega-developments, all of which will be carefully isolated from existing cities. Among them is a proposal for a 100-mile-long linear “smart” city that will be powered by AI and renewable energies. In an image that could have been torn from the pages of a Philip K. Dick novel, the city’s population will be served by hundreds of thousands of robots, theoretically eliminating the need for (potentially rebellious) migrant laborers.

Nor, as we know, was this pattern limited to the autocratic states of the Gulf. On the contrary, a similar pattern emerged in places including San Francisco, London, Moscow, Hong Kong, Seoul, and Shenzhen, where obscene concentrations of wealth have forced the poor and the middle classes to the urban periphery, keeping their problems out of sight. In the democratic borough of Manhattan, for example, where I live, the Related Companies, an international real estate developer, undertook a number of high-profile projects in an effort to add cultural luster and visual diversity to their Hudson Yards Development, a dense enclave of self-contained corporate and luxury residential towers that spreads over 28 acres on Manhattan’s West Side and is marketed almost exclusively to members of the global business class.

Of these projects, the most conspicuous was Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Shed, a sleekly contoured 200,000-square-foot art-and-performance space, clad in lightweight ETFE panels, that is literally plugged into the base of an 88-story luxury residential tower equipped with a swimming pool, business center, health club, screening room, yoga studio, and dog spa. In a mind-bending example of how architectural intelligence is wasted in the interests of a profit-hungry developer, the Shed’s other end is set on tracks so that it can be rolled out to create additional performance space or contracted to make room for a nearby public plaza—allowing the developer to satisfy the city’s demands for both cultural venues and public space while sacrificing the minimal amount of leasable square-footage.

In Chelsea, a dozen luxury residential high-rises, designed by some of the world’s most famous architects, stretch out along the West Side Highway in a sensational display of private wealth. Farther north, along what has become known as “Billionaires’ Row,” “supertall” luxury skyscrapers by firms like Rafael Viñoly Architects and SHoP have pushed the limits of structural innovation in the service of personal vanity and corporate greed, in the process creating exemplary symbols of the elite’s escalating desire to disconnect from the everyday world.

This is about more than gentrification; it is a form of social cleansing. And it is already being accelerated by smart technologies like license plate readers, smartphone trackers, facial recognition technology, and data harvesting, which can be used to clamp down on free speech and weed out “undesirables.” And it is apt to be accelerated further by the effects of climate change, which are likely to induce wealthy and upper-middle-class communities to seal themselves off from both rising sea levels and advancing waves of climate migrants behind ever more elaborate physical and technological barriers.

In the most extreme version of this nightmare future, the final outcome is not a global apocalypse but what is fast becoming two alternate worlds: In one, a small (mostly white) and increasingly isolated global elite, their minds and bodies augmented by brain implants and various forms of cosmetic surgeries, inhabit highly designed “wealth bubbles”; in the other, the vast majority of the world’s Black and brown populations are left to live in a sort of dark ages, roaming the globe in search of a shrinking supply of inhabitable space. Architecture, meanwhile, finds itself stuck in the same place described by the Marxist theorist Manfredo Tafuri in his 1973 book, Architecture and Utopia: sapped of its ideological function, it is forced to retreat into “sublime uselessness”—or engage in “rear guard” actions that have no meaningful social impact.

Not surprisingly, some architects have responded to this crisis by simply doubling down on the status quo. In the fall of 2016, less than a year after Zaha Hadid’s death, Patrik Schumacher, a former partner and now principal of Zaha Hadid Architects, delivered a keynote speech at the World Architecture Festival in Berlin. He advocated for the privatization of all public space, including parks, squares, streets, and government-subsidized housing, provoking a backlash from members of his own firm. Schumacher was a driving force in Hadid’s office as she began to move away from the fragmented, complex forms of her early work toward the more fluid, abstracted vocabulary of her later years—a language that, in hindsight, perfectly suited the neoliberal fantasy of a seamless technological utopia.

Perhaps a more corrosive trend, however, has been the tendency of some architects to dress up a corporate mindset in language that evokes radical designs of the past. In recent years, the poster child for this approach has been Bjarke Ingels of BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group), who has emerged as a favorite of both high-end developers and the mainstream media. Ingels’s formula is summed up in the title of his book, Yes is More, a catchphrase that is a play on Mies’s famous dictum, “less is more.” It suggests a world in which, despite all evidence to the contrary, our current social and ecological crises can be solved without sacrifices of any kind.

Much of Ingels’s design output is made up of easily digestible one-liners, which tend to become blander and more meaningless as they are repeated. The memorable sloped form of his “Mountain” housing complex, for example, completed in 2008 in the Ørestad district of Copenhagen, reappears in watered-down versions in designs for 79&Park in Stockholm, the Sluishuis housing block in Amsterdam, and Via 57 West in New York. In other projects, however, BIG refashions once radical architectural concepts, making them tasteful and unthreatening for his corporate clients. BIG’s “Woven City,” for example, a glorified office park designed for the Toyota Motor Corporation at the base of Mt. Fuji, creates the illusion of urban complexity by dressing up the same sterile scientific management theories that captivated early modernists with smart technologies like robots and driverless cars. Similarly, Ingels’s “Orb,” a kind of gigantic inflatable disco ball that was designed for the 2018 Burning Man festival, is a riff on the inflatables of Archigram’s Instant City, but now entirely hollowed out of their original meaning: what was once intended as a haven of social promiscuity, one that threatened to undermine the existing social order, has been literally transformed into an empty visual symbol.

Nor is Ingels alone in using vague and ultimately meaningless metaphors to obscure rather than clarify a building’s meaning. The smoothly contoured forms of Snøhetta’s King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in Saudi Arabia, we are told, were inspired by the jagged rock formations found in the nearby desert. But by reaching back for inspiration to a time before history, the architects were conveniently able to sidestep the controversial politics of both the Saudi kingdom and the Aramco oil company, which commissioned it. Other architects have compared their buildings to sailboats, clouds, and woven baskets. (A trend partly prompted by the media’s own tendency to brand major new buildings with catchy but ultimately trivializing nicknames like the Shard, the Cheesegrater, and the Shawarma.)

Such practices can be partly dismissed as a canny marketing strategy—an understandable bid for attention in a world where even the most substantive work tends to get lost in the black hole of social media. But they can also be a clever way to gloss over inconvenient political truths. In this larger sense, they bring to mind Orwell’s famous observation that “When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims,” language is inevitably debased. They are a form of evasion, one that contributes to an atmosphere where truth itself has become relative.

One way that architects have pushed back against the suffocating effects of the global marketplace has been through an incremental strategy of small-scale interventions that, when built up over time, can contribute to the overall regeneration of marginal communities. In the mid-1990s, for example, just as globalization was heating up, the French architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal began to develop an affordable housing model for working-class suburbs that sought to minimize waste while maximizing space and flexibility. Inspired by temporary shelters they saw on visits to Niger, they developed a vocabulary drawn from local “found” structures such as agricultural greenhouses, parking structures, and supermarkets. By the mid-aughts, in response to a national urban renewal plan that called for the demolition of 200,000 public housing units, they expanded on that idea, grafting greenhouse-like balconies onto the facade of a 1960s-era public housing project in Paris’s banlieue to create an environmental buffer zone while nearly doubling the size of the apartments. The experiment was repeated in three slab buildings in a 4,000-unit public housing development in Bordeaux.

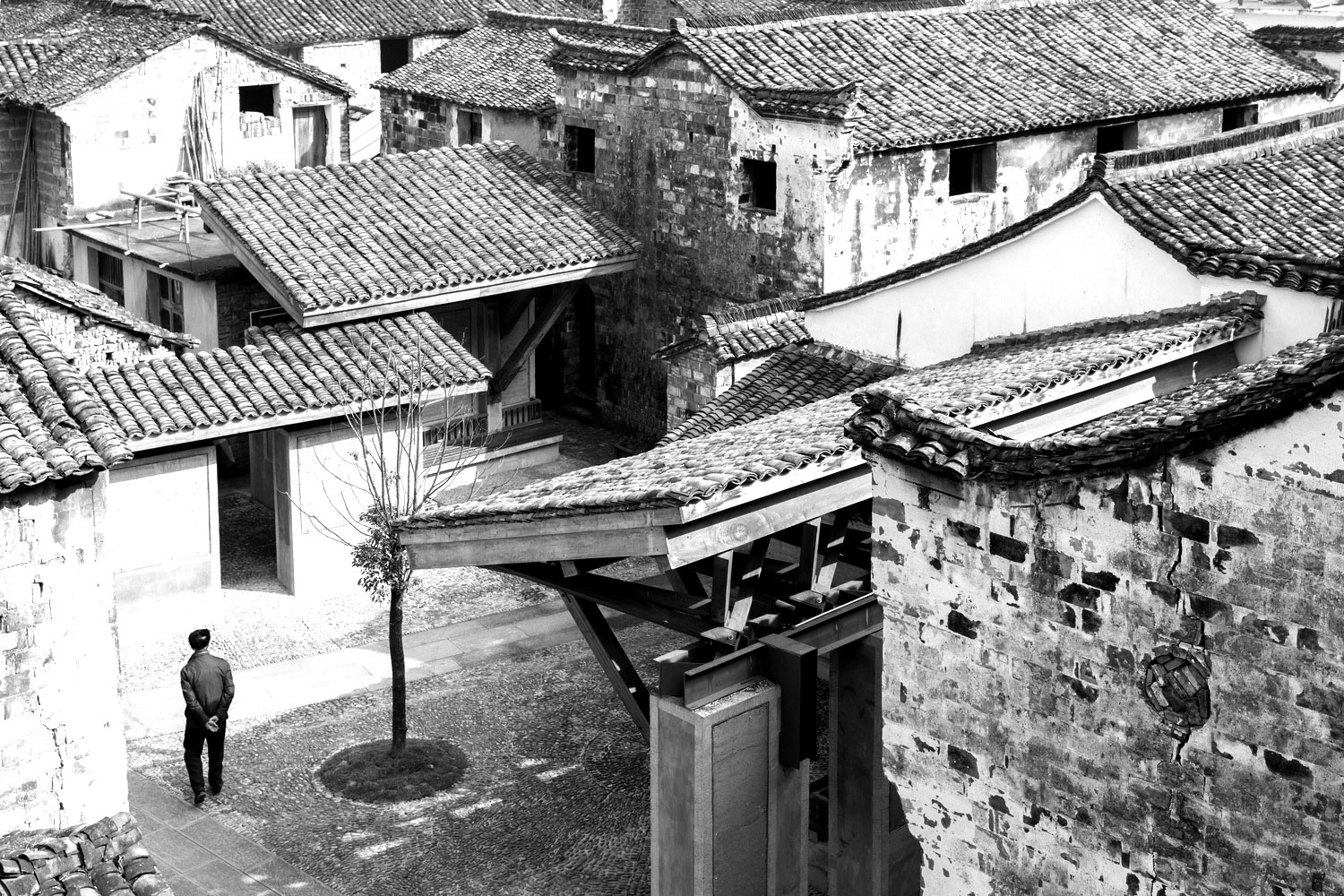

More recently, in China, the architects Tiantian Xu of DnA and Wang Shu have both employed a form of “acupuncture urbanism” (a term coined by the Spanish city planner Manuel de Solà-Morales) to push back against a process of globalization that has gutted rural villages, as the young flee to cities in search of opportunity, leaving the old and infirm behind. In the rural county of Songyang, Tiantian Xu has revitalized several villages with carefully calibrated micro-interventions, transforming a cluster of abandoned farmers’ houses into studios and exhibition spaces, for example, to stimulate tourism and encourage e-commerce. Similarly, in the remote mountain village of Wencun, in Fuyang province, Wang Shu took inspiration from traditional Chinese landscape painting to create a meandering narrative composed of a series of interconnected “scenes,” with houses supported on concrete frames with rammed earth infill.

Perhaps the architect who has taken the most unsentimental approach to globalization is the Berlin-based Francis Kéré. While still a student at Berlin’s Technische Universitat, Kéré raised $50,000 to construct a primary school for 200 students in his native Gando, Burkina Faso—a village of roughly 2,500 mostly poor and illiterate people in the savanna, 125 miles from the capital city of Ouagadougou. Rejecting a view of modernity that was entangled with a history of colonialism, Kéré developed an architecture that drew on the experiences of local people, who traditionally relied on communal cooperation for their survival. Villagers were encouraged to participate directly in every phase of the school’s development, from design through construction. Classrooms were built out of traditional mud brick, with a concrete mix added for additional durability; a vaulted double-shell truss roof, sturdier than traditional straw, was designed to increase cross ventilation. Over the following 15 years, Kéré’s projects in Gando expanded to include teachers’ housing, a secondary school, a women’s center, and a building atelier.

The success of almost all of these projects was built on personal relationships that were forged over years. Many took decades to bear fruit; and all were built on the periphery of the global economy. In that sense, they could be understood as a reflection of a much broader reevaluation of modernity in general, one that has deepened as scholars continue to explore the ties between a Eurocentric ideology built on technology, development, and growth and a centuries-old system of racial and colonial domination. Ideally, they could point to a more effective model for the development of underserved communities at the margins of the global economy—especially if they could garner more widespread backing from a sympathetic government or some interested philanthropic party.

Still, this is an incremental strategy. And it is hard to see how architecture could truly address the enormous social and economic challenges that confront us today without first reclaiming some of the authority that it lost so many years ago, especially in the realm of large-scale urban planning. That would begin by looking beyond simplistic, easy to digest narratives and embarking on a more honest evaluation of the social, political, and economic realities that currently shape the urban realm. It may mean showing occasional willingness to reject a commission, even while acknowledging the very real pressures (financial and otherwise) placed on architects to conform to the status quo.

But it would also require those architects who are most socially committed to directly engage the political realm, where messy issues like civic infrastructure and zoning policies are hashed out. And that can’t be accomplished through individual action alone. One step in this direction would be for like-minded souls to come together and form a group—or better yet, a movement—that can help them hammer out common themes and principles and develop a plan of action. To be effective, this would likely also mean looking outside the profession and connecting with those authorities—from economists to public intellectuals and political activists—who could provide a political and financial framework outside current development norms. And it would require identifying the “other spaces”—to borrow a term used by Team X—where different forms of social organization are still possible. (One of the positive consequences of the decline of the nation-state, for instance, is that it suggests the possibility of forming new alliances across national borders, including between the industrialized North and the Global South.)

Even so, meaningful change is unlikely to happen in the prevailing political atmosphere. Powerful forces would need to align. The powers that be would have to be persuaded that there are human values that cannot be satisfied by slavishly following the demands of the market. And those who have been shut out of the political conversation until now would have to be given more than a voice; they would have to be given genuine political and economic clout. It is, in other words, a long-term commitment—even a gamble. But, at the very least, architecture would regain its sense of purpose.