TOTAL VISION

Sean Canty, assistant professor of architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and founder of Studio Sean Canty, invited Casey Cadwallader, American fashion designer and Creative Director of Mugler, to talk about the intersection between architecture and fashion design, what it means to lead a design practice today, and Cadwallader’s identity as a designer in building on the legacy of the fashion house’s eponymous founder, the late French designer Thierry Mugler.

SEAN CANTY

This issue’s theme of multihyphenation came out of a shift in the landscape of architecture, and in the design field generally. On the one hand, there are mega firms—one-stop shops of consolidation. They have everything, from site planning to interiors to products. On the other hand, there’s a more fluid culture that’s happening out there that’s being promoted by social media. Then, there are practices—like mine and John’s and Zeina’s—where, because we’re caught in between these two worlds, we’re not practicing in the traditional ways that an architect would typically practice.

We thought you would be perfect to talk about multihypenation because you have an interest in clothing design, but also in built forms, and that seems to be at the core of Mugler. Maybe to start off, can you reflect on your own trajectory of moving from architecture into fashion, and now into being the creative director of a major brand?

CASEY CADWALLADER

When I was really young, I wanted to be an architect, and then I wanted to be an automotive designer, and then I wanted to be a jewelry designer, and then I went to architecture school. In architecture school, I was really interested in furniture design, in ergonomics and tactility. And then I became obsessed with this idea of first skin, second skin, third skin, fourth skin, and then the exterior architecture getting back to the skeleton again. I realized that with any of these layers, it’s really just about the interaction with the built world.

After architecture school, I started to feel the pull toward fashion. It felt more exciting. At the time, to graduate as an architect, there was a high chance that you were going to be a CAD slave for 10 years. I thought, I don’t want to do this. I want to be enriched creatively immediately. I want to travel. It’s funny because I applied to fashion jobs and to architecture jobs, and then I got the most fashionable architecture job.

SEAN

Where was that?

CASEY

With Gluckman Mayner, who had done Gagosian and the Helmut Lang stores, and they were going to do Versace—maybe in Hong Kong. I was going to be involved in that, and I thought, “Oh my God, I got the fashion architecture job!” But I knew I wanted to move faster. I wanted something really dynamic. When you’re an assistant in fashion, you’re learning the craft. You’re working on the body and draping on the body and on construction details that relate to garments, working with different fabrics. It’s actually similar to what you would do as an architect, where you might learn how to detail glass with a certain gasket into a stone floor.

Then as you go further in fashion—when you get to creative director—you almost become an architect again. My responsibilities are about making clothes and picking fabrics. But then I’m also dealing with the cultural impact of casting, and who’s going to represent your physical built work? How are you doing the media? What’s the film aspect, what’s the digital aspect, what’s the CGI? What does your showroom look like, what are the chairs? What does your store look like, who’s the architect? Are you designing it yourself? There’s jewelry, there’s buttons, there’s shoes, there’s bags. It’s architecture all over again.

SEAN

Do you think there’s been a paradigmatic shift between individual authorship and branding more broadly? If so, how do you conceive of your individual authorship and then also the bag or the legacy of the brand that you represent?

CASEY

It’s like a dance—and I think it’s true for fashion and also for architecture. There are your hyper-creators, the ones that everything is branded to them and to what they do, and everything they touch has a similarity and a vibe. There’s a totality to the vision. In fashion, working for a brand comes with requirements. Mugler has a DNA, so I have to do this amazing ballet of respecting the existing legacy while keeping my own self-respect and having my own authorship at the same time.

There’s a curation of which parts are going to move forward, and which parts I am going to quietly let go to sleep, and which ones resonate with me as my own creator. Luckily, I think that what worked out for me is that Thierry Mugler and I resonate culturally. As a designer, my physical built work has similarities to his: I love sculpture. I love curves. I love that interaction of how fashion can augment the body in different ways. And he did that too. He was more into costume and into theatricality. And I’m more into pushing the supersonic version of yourself forward. I’m not trying to turn someone into someone else. I’m trying to make them feel themselves as much as possible.

It also depends on which brand you’re working for. If you’re working for certain brands, you as an author are less important. And in other houses, where creativity is more respected, then that becomes what they want you for. It’s like different architecture firms. Some do really amazing law offices all the time; they’re known for their slick, perfect law offices. They can make a ton of money and do beautiful work with beautiful materials. And then other people want to be real creators and to make built form that hasn’t been made before. You have to find the right home so that you can be who you want to be as a designer.

SEAN

To shift gears a bit . . . the pandemic forced a lot of creative industries to rethink their media practices. Social media was quite an interesting landscape to promote yourself, your brand, and your image. With Mugler, you did some really amazing and fantastic runway shows during that period. I’m curious to hear how you leveraged your past experience in architecture with this new role to bring that all to life.

CASEY

When you do a film, not only can you carefully close the zipper and not worry about it before you turn the camera on, but you can shoot it six times, and you can ask someone to jump off a box or do a cartwheel or to have water poured on their head. And then you can edit it from different angles and make sure that your dress looks its best because it looks better from this angle. So you get this total creativity, total control, but also augmented personality, attitude, movement. Entertainment goes up.

Yeah—it was an interesting situation because we had to just do things differently. Everyone stopped doing runway shows and went into doing film. I’ve seen a lot of fashion films in the past and they usually bored the death out of me. So I immediately said, “Okay, if we’re doing film, my promise to myself and to the world is no boring fashion films will come from me.” When you do a runway show, it’s very scary. It’s live. No one’s shoe can fall off. No zipper can be stuck. There’s a tension. That also makes the show exciting because it all has to get pulled off perfectly. Also the model typically has to walk in a straight line toward a camera, which doesn’t really explore their character. It makes them into a bit of a robot—a robot that makes clothes move and that looks pretty. It’s too restrictive.

COVID put us in this place where we had to speak a different language suddenly. And in the end, it opened me up completely because I realized more of the power of media as a communication tool. Fashion is nothing without the person wearing it. Mugler is so much about culture and identity and confidence and power, and that all comes out with the camera. So the idea of going back to doing a regular runway show and shutting all of that back down was a no-go for me. Our last show [held in January 2023, for the Fall Winter 2023 collection] was a hybrid cinema/live performance fusing both of these things together.

During the pandemic, a lot of businesses failed, but we actually established ourselves because we were entertaining to people. We could tell the story of our work and who we were to people through social media. It’s what clinched our growth.

SEAN

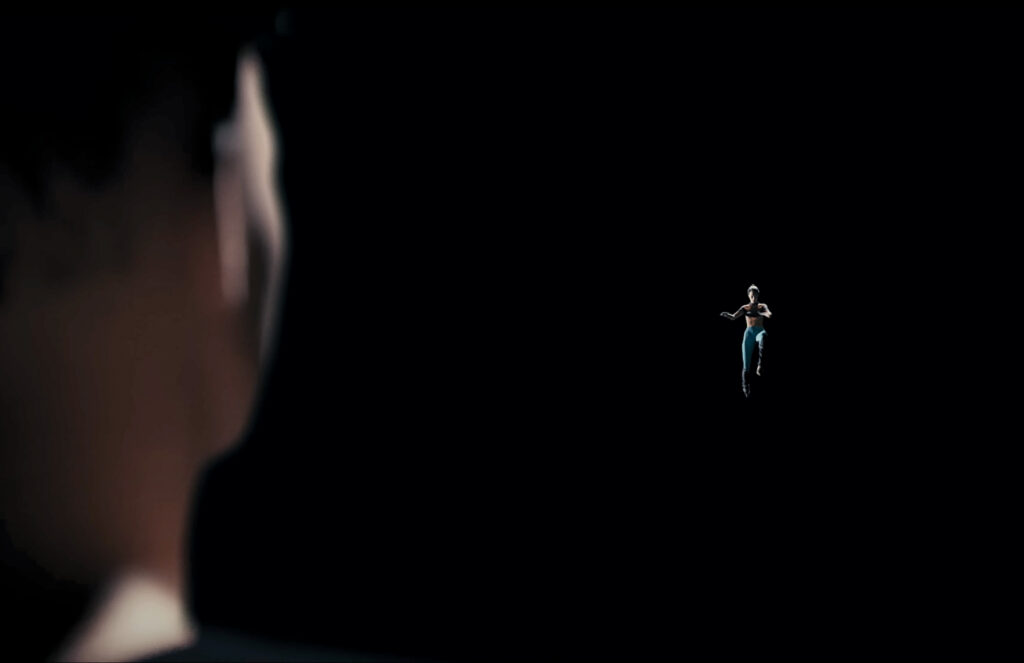

One of the things I felt was super amazing was seeing Dominique Jackson on the runway in part two of the Spring Summer 2021 show, or rather in the film that you made. There is an incredible range of body types and body positivity that is shown in that film, and that is supported by the experimental camera and editing work, which allows for so much imagery that is gravity-defying and defamiliarizing of body movement. All of that, plus the cross-generational model casting and choreography was striking. In some ways, there was no space, almost as if the runway had been exploded into an infinite void, but it was so architectural.

CASEY

It’s true. We tried to negate and collapse and expand the space . . . it’s all meant to be a bit mind-bending. That’s the thing about cameras today; they can be on robotic arms and they can do arcs. They slow down here and then they speed up there. Once I got in there and saw what was possible, I realized how powerful it can be. Think about drone tours of architecture. They can blow your mind because you get to sit there in front of your computer and understand the sequence of space. It’s so different from a nice set of photographs.

SEAN

In terms of the built work of the fashion house, I’m curious about how you’re leveraging your background as an architect to think about some of the retail space.

CASEY

The main way that we’re growing is through wholesale; we’re in big department stores and also niche luxury stores throughout the world. I walked into one store when I first started and I said, “I don’t like this location and I don’t like this materiality. Close it.” Because to me, the crown of the aesthetic is the architecture and how the clothing and the architecture tell this story. So we’ll start doing more pop-up stores and shopping shops, which are built stores within department stores that capture your essence.

Right now, we’re moving offices. Our current office looks like a nicely located accounting office because it’s just white with black carpets. It’s the first time I’m doing a showroom. It’s really about the materiality and how does materiality and sinuousness versus grid create a dynamic that talks about sensuality and logic at the same time?

I love retail design because you get to flex a bit. You get to experiment and you can incorporate sculpture and new materiality. I remember when Rem Koolhaas opened Prada on Broadway—I had my nose pressed against the glass, like, “What’s going on in there?” Because it was just exciting. Also that space, the way that it was performative, that was a real eye-opener for me. I like the idea that the architecture is a production; it’s not fixed and it shows its intent and its purpose, which I think is the opposite of what most fashion houses do. They usually make a pristine, closed image of what the architecture is. I want to try to do something more dynamic and mid-

process. So let’s see how that turns out.

SEAN

How do you think about collaboration in your daily practices? Obviously as creative director, you’re working with many other creative practitioners. How do you balance your own individual authorship with uplifting a kind of collective around you?

CASEY

Everyone thinks that a fashion designer believes they’re God. I’m the opposite. I have to be an influential leader for hundreds of people. Not only am I expected to be creative as a fashion designer, but also creative as an image maker, and good at building the business and being a merchandiser and being a product designer. It’s a different side of the coin, but I’m working with people in public relations, communications, digital, social media, finance, product development. I’m also working with people in the atelier who drape the clothes, and with the shoe factories and jewelry factories. Then when it goes into showtime, it’s lighting designers, set designers, casting directors, and stylists.

It’s an army of people. The most important thing I’ve learned is that I have a very motivational way of being a leader. I want to get the best out of everyone. I want them to feel invested in what they’re doing and know that their part is important. That’s very opposite to the 1980s or 1990s evil creative director who screamed at everyone and threw Coke cans at them. I’m trying to be the new prototype: I want to motivate the death out of someone so that they give you as much as possible. I’ve heard so many stories from my friends in architecture firms that deal with these sorts of energy dynamics, but I think that our generation is much more about motivation and kindness instead of totalitarianism.

So a lot of it is how you are as a leader. And then a lot of it is considering your aesthetics and making sure that you execute them. I used to think I had to do everything with my own hands. What’s really interesting is how much your words can affect the outcome of a built object and trusting the people that you work with to commit to your vision and to help contribute to making that happen. I find that to be one of the most beautiful parts of design.

SEAN

That’s a great segue to my next question: Do you have advice for future multihphenates? Every year I get a cohort of architecture students that come to my office asking, “How do I leverage my disciplinary knowledge to do a lot of other stuff?”

CASEY

Going to architecture school changed the way that my brain works . . . and then I went on to do something else. I’ve always been proud of the fact that I was trained as an architect instead of as a fashion designer because it taught me a lot about representation of ideas, communication of ideas, quality of ideas, cultural significance of ideas. It was such a push in architecture school to communicate all those things.

I mean, it was scary for me to shed the “I’m an architect” skin right out of a five-year BArch program that almost killed me. My grandfather asked, “You’re not going to be an architect?” And I was like, “No, Grandpa. I’ve got other plans.” He said, “You’re crazy.” And I was like, “Maybe I am.”

One of the muscles that was the most exercised during architecture school was that I was going to make sure that you understood my idea even if I had to stay up until 5:00 in the morning and skip history class to finish it to make sure that you understood it. Not all schools teach that level of dedication. That was very, very important for me.

There’s a tendency for everyone to believe that they can only be what they went to school for. If I go to dental school, I’m a dentist for life. That’s the biggest miconception. I think that people are constantly learning through their life; you can ebb and flow and change what you’re doing and that’s just an evolution of yourself as a person.

I hate the idea of going into stasis. My biggest fear is to move to the suburbs and fall off the planet. You can expect as much as you want from yourself. You can learn Japanese tomorrow. You can learn how to do hip-hop dance. You just have to know that you have that potential. So yeah, your architecture brain can turn you into a theatrical designer, it can turn you into a set designer, it can turn you into an amazing baker.

If you go to architecture school, you’re mentally primed to push yourself and to express yourself and to make sure that what you’re doing is clear and purposeful to others. For students, you need to know that your originality and the things that make you different are the things that make you special. You have to stay on that path. The most dangerous thing is trying to emulate the aesthetics of other people. They can excite you and they can get your blood pumping, but you have to know what your own craft is and what that looks like and what that means and to follow yourself and push yourself to do that better and better and better.