Who is the Architect?

Parsing distinctions between architecture and “mere” building has been a preoccupation of thinkers and practitioners since ancient times. The very difficulty of defining neat disciplinary boundaries is intertwined with the practical challenge of defending a precarious marketplace position against the incursion of ever more specialized and automated expert domains. Shifting attention from effects to their causes, let’s pose the question in a more edifying way—not What Is Architecture but rather Who Is the Architect? Is “the architect” a corporate body or an individual agent? A vocational identity or a professional singularity? A servant to power and wealth or an intermediary between capital and labor? Some argue that the architect is a building design specialist who coordinates the work of other construction industry specialists; others assert that the architect is a generalist designer of wide-ranging remit but one endowed with special cultural authority for building.

In the middle of the 19th century, the American architect was an individual, one variously fashioned as gentleman, dilettante, artist, artisan, master builder, surveyor, or construction supervisor. During this pre‒Civil War period, a subgroup of culturally elite and public-spirited, if paternalistic, architects began advocating for and asserting an exclusive claim over their self-anointed professional title but with some paradoxical results. If in ancient times the shifting identities of the architect tended to range widely over a spectrum of roles—from project initiator to building executor to design mediator—in modern times the architect’s role seems to have become ever more narrowly prescribed within the legal bounds of normative professionalism.

In consequence, the architect’s identity has been reductively distilled into the role of building designer. Essentialized and perpetuated over the late-19th and 20th centuries through the institutional logics of architectural education and state registration, this definition has both limited the profession’s influence within the broader construction industry and circumscribed its jurisdiction of expertise with respect to a host of competing and complementary knowledge domains. While architects may derive titular authority from the licensing powers of the state, their practices serve primarily as handmaidens of private interest. Meanwhile, the polyglot of possible performative responsibilities grouped since antiquity under the single moniker of “architect”—utopian visionary, urban planner, construction innovator, real estate developer, housing advocate, environmental steward—has been disciplinarily divested in the modern era and then reconstituted under various corporate umbrellas, civic institutions, and multidisciplinary firms. Who is the architect, actually: an enterprising cultural consulting agency or a problem-solving agent of the public good?

John Gast, American Progress, 1872.

Indeed, architects and designers today, both individually and collectively, embody all the tensions that these blurry boundary conditions imply. Whether as sole proprietors or corporate entities, as urban and architectural designers or develop-design-build consortiums, they are networked and intertwined through a variety of cultural tropes and caricatures, educational establishments, guild associations, political frameworks, technological regimes, and economic interests. Each plays their part among the plethora of historically accumulated roles that they have asserted for themselves, ones that they have devolved or surrendered to others, or else that have been socially assigned and assimilated over time. Paraphrasing Karl Marx, it may be suggested that, primary among all else that they may construct, architects “make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please. . . .” On the way to considering what architects actually make, let’s take up the question of how the contemporary American architect was made.

***

From our early-21st-century perspective, it may be difficult to fathom how architects, or even the concept of architecture, first arrived in the Americas. The Indigenous peoples of these continents had, of course, already been laying out and constructing shelters, settlements, and ceremonial compounds for many centuries in advance of European colonizers’ royally asserted claims. So in the anthropological sense, the spatial, utilitarian, and symbolic culture of building—what today we call architecture—was already present at the event horizon of European contact on the Atlantic shore.

Just as the introduction of foreign biological pathogens among the Native populations had tragic results, so we might imagine that European building traditions overwhelmed and appropriated Native material cultures, and over a relatively short interval of time. It is even more ironic, therefore, that colonizers’ empirically drawn observations of “primitive” Indigenous practices should have served as affirmations of the learned discourses, and myths of origin, then proliferating in the halls of Europe’s royal academies. Those very theories and assumptions had, in turn, been pieced together from interpretations of archaeological remains and fragmented readings of classical manuscripts preserved from the ruins of Mediterranean antiquity. As these processes of transmigration and adaptation of building ideas and practices suggest, it was by way of tradition and along a viral path of cross-cultural exchange that the ambiguous figure of the American architect emerged.

The architect, as we deploy the concept today, thus embodies a hybrid genealogy, one that is both idealized and mythologized from the distant past even while it is being continually reshaped to satisfy the performance expectations of shifting political economies, societal assumptions, and technological means. It may be argued that this situation is in no way unique, that similar circumstances are at play in the ongoing transformation of every learned profession and disciplinary domain, every craft process and division of labor. Despite, however, any apparent narrowing of the professional architect’s function within contemporary society, a more multiplicitous and indeed archetypal concept of the architect still persists.

Among all those who have historically taken on the role or assumed the title, or both—whether drawn from the lines of autocratic rulers, priestly classes, masters of craft, military conscripts, artisans, artists, intellectuals, or revolutionaries—all prior historical incarnations of the architect coexist within the cultural imagination. Besides the institutional organization of state-licensed professionals who share definitive obligations to the built realm for the public good, who, in the broader sense, is the architect? A term now widely applied both euphemistically and across a variety of fields of action unregulated by the state, “architect” in our age designates those individuals who mediate between power and knowledge to serve as mechanisms of social and material transformation. Thus, as both symbol and personification, “architect” is a metaphor for the agents of vision and know-how.

***

The historically derived idea of the architect that arrived in North America was aligned, as agent and actor, with the aims and ambitions of hegemonic powers—church, throne, landed gentry. Most emblematic, perhaps, of this model are those 17th- and 18th-century recipients of royally granted commercial charters who established their tidewater tobacco plantations and grand estates. Landowners could serve as their own surveyors and architects, drawing their inspiration and geometrically proportioned plans from Palladian folios, we imagine, with an imported set of precisely calibrated drafting instruments. These ambitious building schemes were realized, in turn, under the master/architect’s direction, by the crafting hands and forced labor of indentured servants and enslaved people. In such a model, the architect was omnipotent—the owner of both land resources and construction laborers, both the conceiver and executor of a totalizing vision.

Virginia Land Office Warrant Number 229 issued in 1779 to Joseph Cabell, assignee of Sargent Gabriel Penn, to receive 200 acres of land in return for Penn’s service in the French and Indian War.

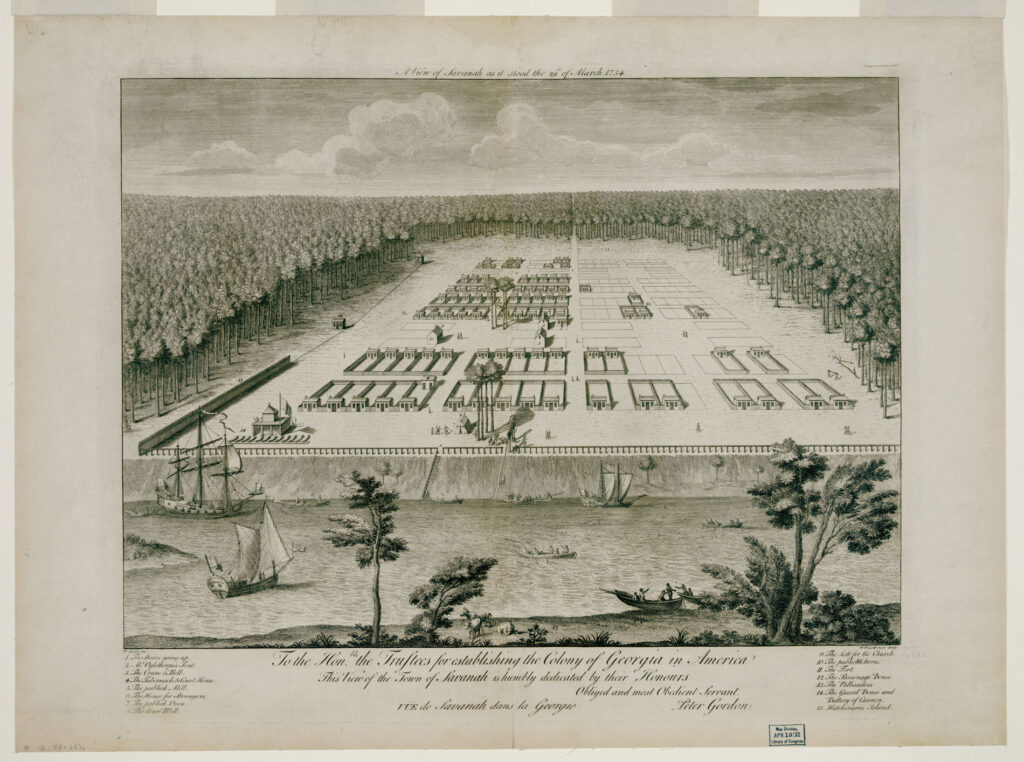

Engraving by Pierre Fourdrinier after a drawing by Peter Gordon, a view of Savannah as it stood on the 29th of March, 1734.

At another increment along this social gradient, we can discern other models of the social assembly of the architect, this time arising from the bottom up. Speculative companies and striving individual colonists (likewise royally chartered) arrived in search of opportunity and profit. Once removed and at some distance from reigning European authorities, and stoked by the immediate demands of subsistence and self-sufficiency followed by mounting desires for political self-determination, they began to develop alternative arrangements of urban settlement—Boston, Philadelphia, Savannah, New York—and to provide diverse forms of shelter for a growing population.

Simple dwelling places might be planned and provisioned by their intended inhabitants who, as owners, served simultaneously as their own architects and builders. Once stretched beyond the limit of what individuals or neighbors could build for themselves, then companies of craftspeople emerged. Carpenters and masons could work for prospering owners on a contractual basis with the mechanics and their clients collaborating back and forth with each other on the particulars of layout and material finish. Any desired ornamental embellishments could be adapted from carpenters’ handbooks of simplified classical details.

As owners’ requirements—say, for a small manufactory, private residence, or public facility—exceeded the limits of contractors’ vernacular means, builders might employ in-house drafters to provide more elaborate or specialized designs. Having graduated from the carpenter’s bench to a drafting table, such enterprising individuals might eventually be commissioned by several builders and then emerge one day to assert their own business independence. They would no longer be mere builder’s drafters; rather, by making an end run around the builder to deal directly with an owner or client, they were setting themselves apart—as architects.

These illustrative accounts are themselves assembled, gleaned from diverse sources, and may be apocryphal. What is not in doubt, however, is that by the early 19th century, several competing models of the American architect were in play. The architect could be a discerning dilettante designing for themselves or others. The architect could be a speculative builder capable of providing serviceable in-house building designs informed by their accrued craft experience or profit-making acumen. The architect could be a third, mediating party—an owner’s design-advisor and then their intermediary agent coordinating the building trades on-site. By mid-century, architects might be the descendants of moneyed classes, ascendant designing builders, freshly arrived “professional” architects from England and elsewhere, or the journeymen drafters who had gained experience in the drafting rooms of the other three. Architects were separating themselves from builders to more closely associate themselves with owners and the edifying interests that they conferred.

Such an eclectic mix of claimants to the single designator of “architect,” it was argued, tended to confuse the public and frustrated efforts toward the enhancement of professional esteem. These were the concerns motivating an elite group of architects of diverse backgrounds who met in New York City to establish the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1857. Their professional status-building efforts, first at local levels and then nationally, continued to gain momentum over the course of the century. And, when the fractured nation emerged on the other side of the Civil War and Reconstruction, a new urgency—driven by an economic expansion that fueled a building boom—motivated the drive toward a more unified and standardized profession. That goal was advanced by the establishment of university-based architectural education, the proliferation of architectural journals, and the spread of transcontinental systems of transportation, distribution, and communication.

These efforts also included the drafting of standard forms of contract establishing the architect as the owner’s agent in all dealings with contractors as well as the stipulation of a mandatory fee schedule for all AIA-member architects. Neither of these moves were without their own structural paradoxes, however. How could the architect be the owner’s agent in drafting a contract and also perform the role of impartial judge of the contractor’s work in cases of the architect’s own errors or disputes over changes and charges? Indeed, how could architects be trusted to keep costs in check when their fee was based upon the cost of construction? And by the way, where did that percentage scheme originate, and what was its basis? Derived from dubious European precedents, the AIA fee for full services failed to account for the increasingly intensive and costly obligations for cost control and jobsite supervision; but, once established as a rule it became almost impossible to change. To assuage public concern, these architects pointed to their shared ethical code conveying their status and trustworthiness as gentlemen and members of a bona fide profession; and to further distinguish themselves from non-AIA architects, they forswore any financial interest in building.

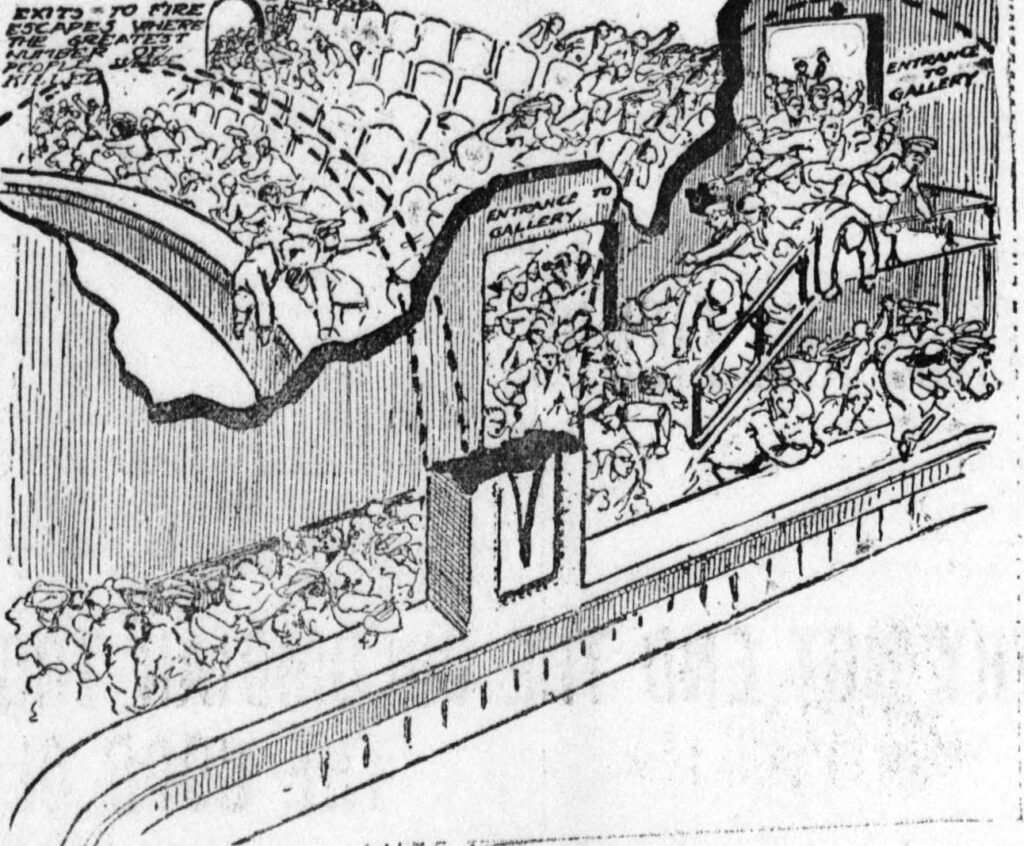

Despite the AIA’s moves toward defining new ethical norms of professional virtue, commercial interests continued to hold sway. In one arena, however, the advocates of architectural exclusivity fell on the side of progressive reform. Toward the turn of the 20th century, the quality and safety of construction was a rising public worry. Of particular concern was the question of the fireworthiness of buildings, an anxiety intensified in 1903 by the loss of 600 lives in the inferno of Chicago’s Iroquois Theatre. This matter seized public attention due to a steady drumbeat of tragic conflagrations in cities across the nation—Baltimore, San Francisco, New York—resulting from shoddy construction, inadequate egress affordances, and apparent laxity, and even corruption, in the regulation and enforcement of building safety.

Iroquois Theater, view of the ruined stage after the fire taken from the balcony, Chicago, Illinois, January 4, 1904.

Chicago History Museum (ICHi_036007)

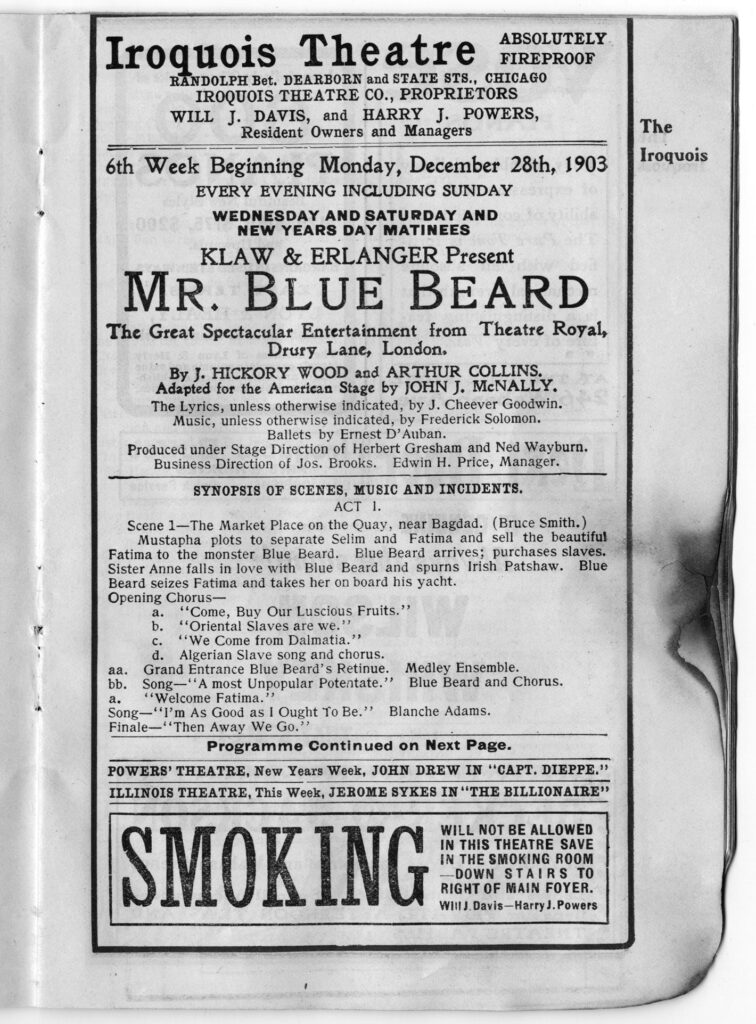

Charred program for Mr. Blue Beard from the day of the fire, Iroquois Theater Chicago, Illinois, 1903.

Chicago History Museum (ICHi_34981)

Cutaway drawing of the Iroquois Theater in Chicago with the panicked audience trying to flee the onset of the Iroquois Theater Fire, 1903.

Architects of whatever ethical stripes were not immune to these concerns. The cascade of public sentiment and the lobbying by interested parties precipitated action among legislatures for state regulation of the title of architect. Beginning with Illinois in 1897, state registration laws, governing boards of architecture, and licensing examinations were established in 20 states by 1920 and in a total of 44 states prior to the United States’ entry into World War II.1 In the same period, engineering fields steadily became more specialized, standardized zoning ordinances were enacted, and uniform building codes were adopted. And the remit of architects’ coordinating responsibility, and liability, for public health, safety, and welfare continually increased.

After the war, as had been the experience after World War I—and the Civil War before that—quantum leaps in technological development that resulted from wartime efforts led to profound changes across the entire construction industry sector and indeed in every segment of everyday life and economic activity. Advances in manufacturing, transportation, and communication helped consolidate technical standards and labor practices where local economies and parochial protections had previously held sway. Postwar population growth, suburbanization, and a growing middle class increased demand for architects’ and designers’ services to facilitate the transition to a modern way of life. The AIA, which from its founding had been so keen to assert its members’ claim to a legally enforceable but narrowly defined professional title, struggled to adapt its 19th-century ethical mores to the business-focused values of an increasingly corporatized and profit-driven clientele. Architects’ rising exposure to risk and liability became associated with design novelty, and the evident separation of design education from fundamental construction know-how further stoked public uncertainty about the value of an architect. Among a cascade of ironies, architects were economically outpaced by their erstwhile rivals, the general contractors, to whom they had inadvertently ceded their construction coordinating responsibilities due in part to the inadequacy of their then AIA-mandated fixed-percentage fees.

Architects—whether by education or experience, whether titled or untitled—proliferated across all sectors of the construction industry. They applied their design, technological, organizational, and managerial acumen directly on the building site and contributed to the development of skill sets and knowledge domains later claimed as specializations by construction managers, fabricators, product representatives, real estate developers, permitting offices, financial institutions, and other public agencies. Among all the principals, partners, and associates; the specialized employees of small firms, boutique design firms, corporate firms; name-brand starchitects; anonymous house designers; your local design-builder; production firms; estimators; professors; potentates; and an expanding slate of essential consultants . . . who is the architect?

***

At a faculty gathering to celebrate the beginning of another academic year, I asked what I thought was an innocent enough question. “So, are you an architect?” The response was not quite what I expected. This partner of a graduate student, both of whom were newly arrived from abroad, responded a bit hesitantly at first and then answered my question.

“I suppose I’m a designer, here,” she shrugged, with a quick glance to her spouse. “Back home I’m most certainlyan architect,” she said, explaining that she had been educated and licensed as an architect in Italy. She recounted being chastised during a recent job interview that she was not allowed to call herself an architect because she is not licensed anywhere in the United States.

“Aah,” I nodded, taken slightly aback but then slowly recognizing the weight of “all the dead generations” of architects bearing down upon that single moment. After millennia of sedimentation of the traditions of architectural practice, their transnational migrations, and sociopolitical and technological transformations, is this what the culture of professionalism has become? The regulation of a title meant to safeguard the health, safety, and welfare of the public is also an instrument of market protectionism in the competitive play of jurisdictional monopolies, interstate commerce, and global exchange. Isn’t it time to admit that the legal wrangling to define who is singularly entitled to the mantle of architect is a 19th-century argument with diminishing 21st-century returns?

The 20th-century movement toward state regulation of the title was a necessary action to establish clear legal limits and elevate the public interest as counterforce to the unbridled play of predatory capitalist development. The privilege of a professional title carried both the benefits of trust and the burdens of immense liability that in all but the simplest of constructions quickly exceeded individual architects’ capacities and competence. The increasing scale and complexity of client-owners’ projects and ambitions as well as constructors’ trade and organizational specializations thus transformed “the architect” from individual practitioner with a few drafters into a corporate body comprised of an orchestrated retinue of partners, employees, and consultants enacting their shared and delegated authority.

The widespread adoption of state registration laws was aided and abetted by two other developments. First, the requirement of an accredited university degree became, over the 20th century, the dominant route to professional architectural licensure, significantly limiting the range and diversity of historically available pathways into the field. The academization of the discipline significantly divorced the artistic, techno-scientific, and discursive aspects of design composition—evaluated as individualistic pursuits—from the improvisational and collaborative approaches demanded by the complex business and construction constraints of day-to-day practice. With their curricula thus lacking the grounding of practical experience, university degrees were deemed to only partially satisfy the rubric of professional preparation; the license was therefore only conferrable through the fulfilment of a subsequent period of office training and written examination—an examination that still presumed the architect to be an individual, autonomous actor.

Architects are not autonomous agents, however; their functional responsibilities for upholding the public good in the built domain have been ever more widely distributed among a retinue of governmental processes and industry standards. This fact constitutes a second developmental trend. Concomitant with the adoption of state registration laws, states and municipalities have embraced a host of administrative protocols and procedures for enforcing adherence to the very responsibilities that architectural licensure was meant to uphold. Stimulated in part by initiatives taken by Herbert Hoover’s Department of Commerce in the 1920s, governments have adopted uniform plumbing and building codes, established permitting agencies, and mandated construction inspections in order to define and regulate standards of fire safety, building occupancy, construction type, and energy performance. They have shaped municipal codes in response to changing legal precedents (in the case of The Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Company, 1926, for example) in order to manage urban growth and development. They have done so through establishment of city planning departments and the maintenance of master plans, zoning ordinances, review boards, urban design commissions, and neighborhood planning units, each process operating within some principles of democratic participation and local control. At the same time, universalizing technical standards, protocols, and specifications have been incorporated within the manufacturing sector and the construction industry worldwide through the intervention of national and international standard-setting organizations.

While developing planning strategies and approaches to matters of location, building use, and design identity at a multitude of scales, today’s large multidisciplined architectural firms are ever more defined by the intricacy of their coordinating roles. The design teams demanded for complex, capital-intensive building endeavors are constituted by an expanding host of engineers, construction managers, estimators, expert consultants, design assistants, manufacturers, and fabricators in the quest for quality assurance and the silver, gold, and platinum markers of external certification and “green building” validation. We wonder, however, which among this litany of expert domains, integrated functions, rules, checks, and obligations is not subject, eventually, to automation. Specific decision-making functions—whether lodged within public agencies, industrial sectors, or private architectural practices—are subject to decomposition into their respective routines and then delegated to paraprofessional plug-ins, digital assistants, and artificial intelligence engines. If the life-safety functions of the architect, the defining attributes of the licensed profession from the 20th century to present day, were preloaded in their design technologies as some deus ex machina defaults, what then would become of that parochial title, architect? Out of all the possible hybrid manifestations offered by history, is there not any alternative to replacing one reductive definition of the life-safety architect with a new and totalizing vision of the architect as a technological fait accompli?

***

In all of this, my overarching effort has been to disentangle overly mythologized notions of “the architect” as an individual of autonomous personification (all agency, all the time!) from the more intertwined functions a democratized profession plays in the design and construction of the physical world, in the spatial constitution of social orders, and in efforts to critically reform or resist them. Who the architect is is not separate from what the architect makes or, for that matter, from who or what makes the architect, in any age or time. Over the course of history, architects have emerged both from the top down and from the bottom up and then merged in the middle to forge their mediating roles.

What architects, designers, and drafters made over the 20th century were their tools of practice—the instruments that articulated, organized, and standardized each aspect of social and technological exchange that had once been conveyed on-site, largely by word of mouth, and in direct conversations with construction laborers. Under shifting logics of governance and production, architects withdrew by degrees from direct participation at the construction site into ever more detailed and rhetorically focused intermediary representations—their plans, sections, and rendered perspectives; construction drawings and specifications; the shop drawings, change orders, and certifications of substantial completion; and now into digital models and simulations, the residues and proofs of the labor of many anonymous architectural laborers, their individual presence and collaborative skill.

If, as suggested at the outset, architects make their own history but not under conditions of their own choosing, then whatever architects may make next, so they will likely make of their profession. One can imagine forms of spatially distributed intelligence, both metaphor and material evidence of their know-how, and their vision. “The architect” is neither a fixed entity nor limited to any singular archetypal figure but rather is a collective body of knowledge and individual problem-solving ingenuity; a form of mediating agency, still subject to ongoing reinvention within changing times and cultural constraints.