After the Flood

It is increasingly clear that one of the major female architects of the 20th century was the Italian Lina Bo Bardi, who emigrated to Brazil in 1945 and made a name for herself there. But this claim is both correct and insulting: she does not need the qualifier of her sex to be seen as one of the outstanding practitioners in the history of modernism. She must have encountered many difficulties in her career, as a woman in a field still gendered as male, a European in Brazil, and a modernist outnumbered by traditionalists. Yet from the very beginning she asserted herself professionally with projects of uncommon strength and originality. Despite the extraordinary oeuvre she has left behind, Bo Bardi has not gained the recognition she deserves in surveys on Brazilian architecture, with their perennial focus on Oscar Niemeyer, Lúcio Costa, and Affonso Eduardo Reidy. Nor has she received the professional accolades and scholarly attention given to Eileen Gray, Lilly Reich, Charlotte Perriand, or Ray Eames, even though no woman of her generation built as much. A reassessment of her career is long overdue. In her case, one suspects, gender inequality is still overshadowed by that other form of asymmetrical power relations, the North/South divide.

Lino Bo Bardi’s Glass House

Born in Rome in 1914, Lina Bo studied at the city’s school of architecture, dominated at the time by conservatives like Gustavo Giovannoni and Marcello Piacentini, two of Italy’s most powerful architects under Mussolini. After graduating in 1940, she left for Milan, which was far more open to modern architecture and less bound by the Roman past or the regime’s imperial leanings. Soon after her arrival, she found work in the studio of architect and designer Gió Ponti, director of the magazine Domus, which, like its rival La Casa bella (but somewhat less critically) was devoted to design.1 Work in Ponti’s studio gave Bo experience in different fields—furniture, fashion, and household goods, as well as architecture and urbanism. When Italy entered the war in 1940, Ponti left Domus and a year later founded Lo Stile, for which Bo produced several covers. In January 1944, she became one of the Deputy Directors of Domus, a position she held until 1945.2 She also contributed articles and designs to several other magazines, including Grazia, L’Illustrazione Italiana, and Milano Sera. For a newcomer, and a woman, Lina Bo was extremely successful.3

War undoubtedly brought difficult times, but Lina Bo’s own reminiscences about this period of her life should be treated with caution. Years later, she claimed to have joined the Resistance and the clandestine Communist Party: “The years that should have been ones of sunshine, blue skies, and happiness I spent underground, running and taking shelter from bombs and machine guns. . . . One article I wrote (a criticism of urbanistic architecture) in an editorial of the ‘Domus’ magazine deserved the attention of the Gestapo. I escaped by a miracle . . . underground!”4 For someone who was “underground,” Bo was very visible during the German occupation, working for a high-profile magazine. Denial and wishful thinking may have played a role in shaping her remembrance of those years: her somewhat streamlined recollections represent the views of the Lina Bo of the 1970s and ’80s, by then a left-winger deeply committed to the disenfranchised of her adoptive country.

Shortly after the end of the war, Lina Bo met Pietro Maria Bardi, a well-known art dealer and journalist, whom she married in 1946 after he was granted a divorce from his first wife. If Bo was a communist in 1944, her marriage reveals a talent for political accommodation. Bardi had been one of the unofficial ambassadors of modern Italian culture under Fascism, close to Giuseppe Bottai, minister of the Corporations until 1932 and later governor of Rome, and a proponent of sozialfascismo, which conservative revisionists sometimes gloss as left-wing Fascism.5 Sozialfascismo was in fact the modernist wing of the Fascist party, the rallying point of those who fought for modernity and managed to keep the regime open to the avant-garde. Though very successful initially, modernism met with increasing hostility after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. It took courage to defend the new art and architecture to the extent that Bardi did in the late 1930s. But he did so as a loyal fascist, from within the parameters set by the regime.6

Bardi was a highly respected connoisseur who was often called upon to authenticate paintings or advise on restoration—surprising feats for an autodidact who never attended college. At the same time, he developed an informed passion for modern architecture and quickly became one of the finest interlocutors of Italian rationalism, the Italian brand of high modernism—the Corbusian creed reinterpreted in the light of a Mediterranean sensibility.7 In Brazil, the Bardis would continue their journalistic activities by publishing and directing the magazine Habitat. A friend of all the important rationalist architects—Giuseppe Terragni, Giuseppe Pagano, Adalberto Libera, Luigi Figini, Gino Pollini, Mario Ridolfi—Bardi was also acquainted with the famous European modernists. In 1929, he covered the CIAM meeting held in Frankfurt for Belvedere. Four years later, he again took part in CIAM, travelling from Marseilles to Greece with Le Corbusier aboard the Patris II. Bardi’s passionate interest in modern architecture, as well as his personal connections to some of the International Style’s greatest exponents, were to be of great significance for Lina Bo, who was to follow, at least initially, the same aesthetic path.

Not long after their marriage, the Bardis moved to Brazil with all their belongings. It is not clear why they emigrated to a country he hardly knew and she not at all, and with no job prospects. Bardi may have felt that his huge library and art collection were in danger, given his previous involvement with fascism. Be that as it may, political concerns clearly weighed heavily in their choice of destination and in the connections they made on arrival. But politics also had much to do with their increasing distance from right-wing regimes and with their evolving artistic orientation. The cultural and ideological roots of Lina Bo and Pietro Maria Bardi are of great richness and complexity, and their extraordinary contribution to the arts in Brazil is linked in many complicated ways to their Italian past.

Sometime after their arrival, they met Francisco de Assis Chateaubriand Bandeira de Melo—journalist, senator, and diplomat. Owner of the powerful newspaper chain the Diarios Associados, Assis Chateaubriand, as he was known, used his immense power as a newspaper magnate to put together the best collection of European art in Latin America. With the help of Bardi’s expertise, he was able to identify the most important works of art that the postwar recession had made available to the art market. Pressuring São Paulo’s wealthy industrialists and bankers, he was able to raise funds for a remarkable art museum, which includes works by Bosch, Mantegna, Velasquez, Goya, Titian, Rembrandt, Franz Hals, and all the major Impressionists.8 Lina Bo Bardi was responsible for the temporary headquarters of the museum, but it was a work of interior design, situated in a preexisting building (1947). Her first real project was the residence she built for herself and her husband from 1950 to 1951, and known today as the Glass House.9 It marks the beginning of her remarkable architectural trajectory.

The Glass House, 1950–1951

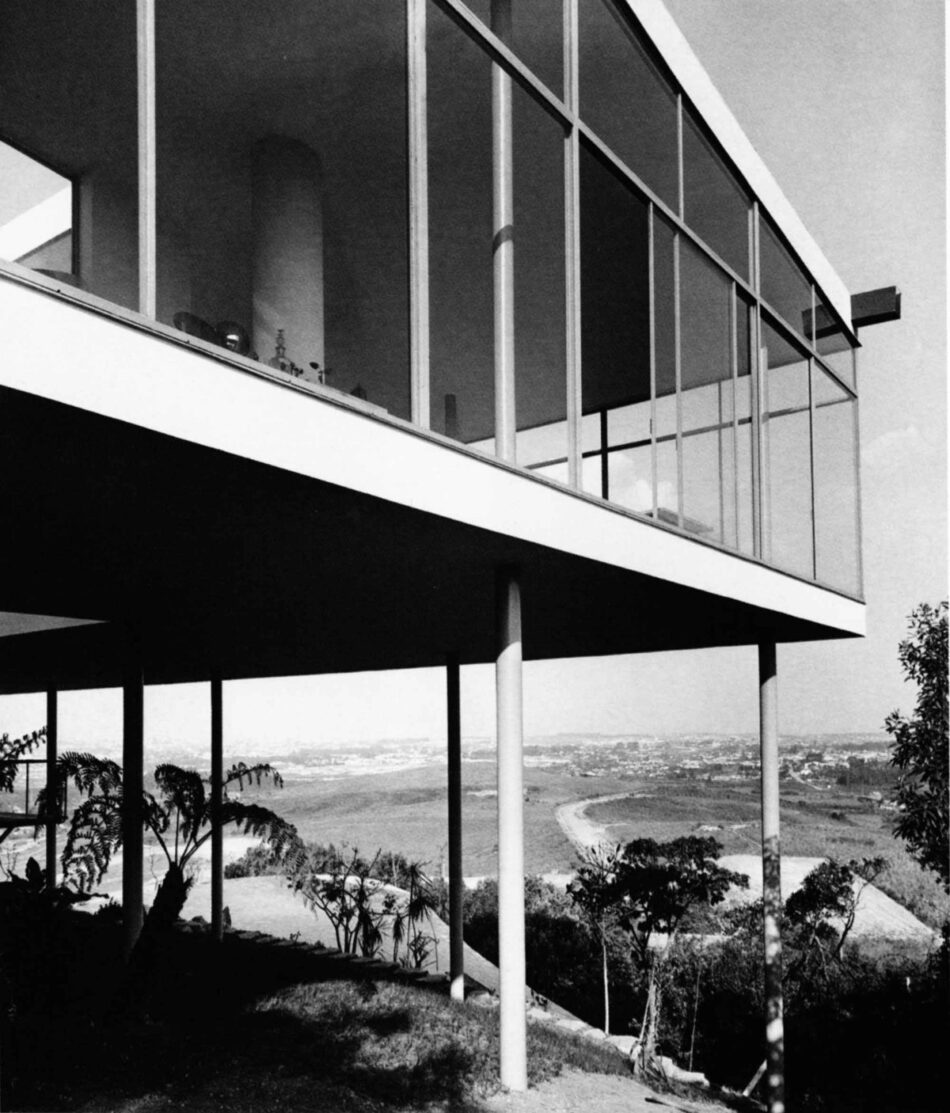

Though now part of the fashionable suburb of Morumbi, the Glass House once hovered over the remnants of the original rain forest, the mata Atlãntica, with its dense, exuberant fauna and flora. Suspended high above a sea of green, the building resembles an International Style treehouse. A swaying metal staircase connects the winding path to the living spaces above, its seeming instability in keeping with the adventurous atmosphere of the house, which seems to anticipate Italo Calvino’s 1957 tale, The Baron in the Trees.10 The Bardis lived surrounded by armadillos, opossums, sloths, and wildcats; tropical birds flashed intermittently amid the foliage.11 Their house was virtually a belvedere. Great swaths of unspoiled vegetation had already been cleared in 1950, when the new road was cut. An environmentalist long before the term existed, Bo Bardi had the forest replanted around the building.12 Even though the entire area is now built up and the wildcats are long since gone, the lots are large and densely planted, and the Glass House is almost invisible from the road, concealed by a thick screen of vegetation. Though Bo Bardi would later challenge the opposition of nature and culture, the contrast between the abstract aesthetic of steel and glass and the lush green of the forest was an important element of her parti from the start.

For structure, Bo Bardi opted for that of the paradigmatic Dom-Ino house: spindly supports sandwiched daringly between two slabs of concrete. Thin, Corbusian pilotis, set back from the perimeter to permit a free facade, raise the glass box elegantly aloft. Le Corbusier was an obvious point of reference: the Bardis arrived in Rio a few years after the completion of the Ministry of Education and Health building (1936-43), which he designed with the help of Lúcio Costa, Affonso Reidy, and Oscar Niemeyer, among others.13 Then one of the world’s largest modernist buildings, it astonished Lina Bo Bardi, who wrote in her diary, “the Education and Health Ministry building advanced like a great white and blue ship against the sky. The first message of peace after the flood of the Second World War. I felt myself in an unimaginable country, where everything was possible.”14 Le Corbusier was more than a famous name; he was also a friend of Pietro Maria Bardi, who continued to correspond with him after his departure from Italy.15

But the presence of Mies also reverberates throughout the house, particularly in its walls of sheer glass.16 Though in theory the sliding panes served to bind the interior and the exterior, Bo Bardi’s glass box seems to imply a purely retinal connection to its surroundings, filtering out the less cerebral sensations of touch, sound, and smell.17 The very foliage outside the glass walls is treated pictorially, almost like a mural. Perhaps, too, the way glass insulates the house from its lovely surroundings betrays an émigré’s reaction to a new world—a world not exactly hostile but not yet fully embraced. For all its apparent connection to nature, the house emphatically stresses the classic opposition between architecture and the environment: it is a hothouse in reverse. Just as Gerrit Rietveld’s Schroder House is always photographed with its windows carefully staged so that the panes are perpendicular to the walls, so too Bo Bardi’s Glass House is always photographed as an inviolate, closed box: architectural photography carries a truth of its own, with the power to challenge received truths and authorial intentions.

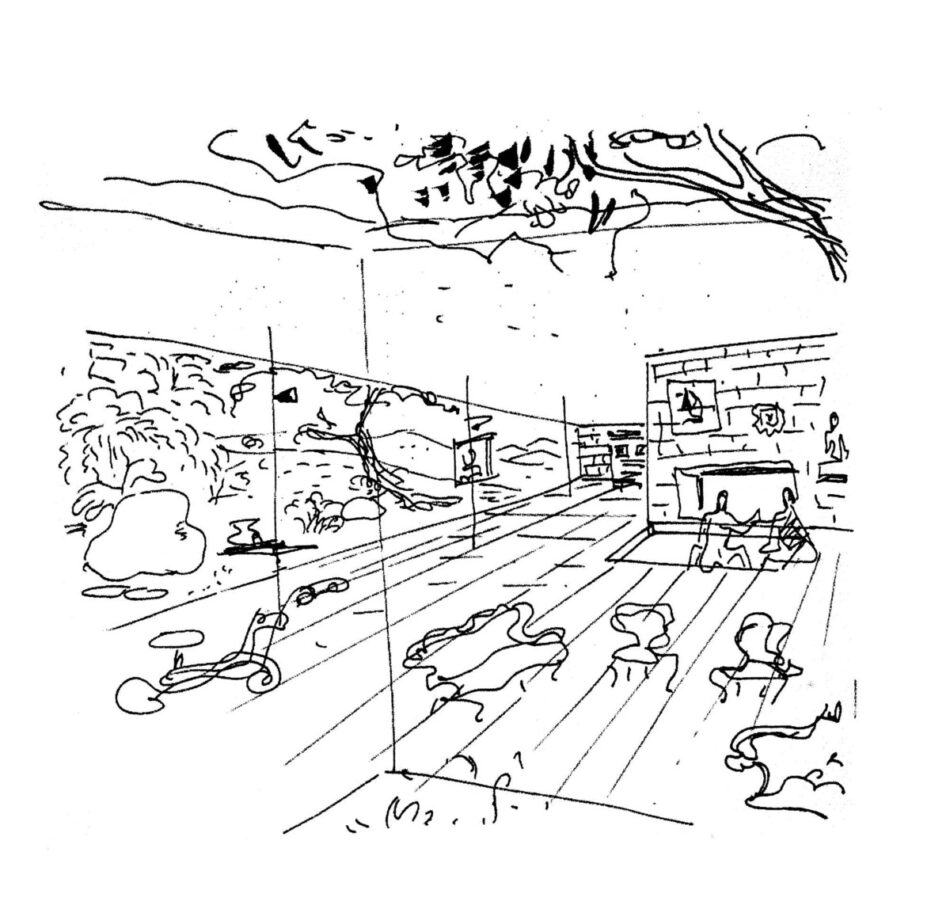

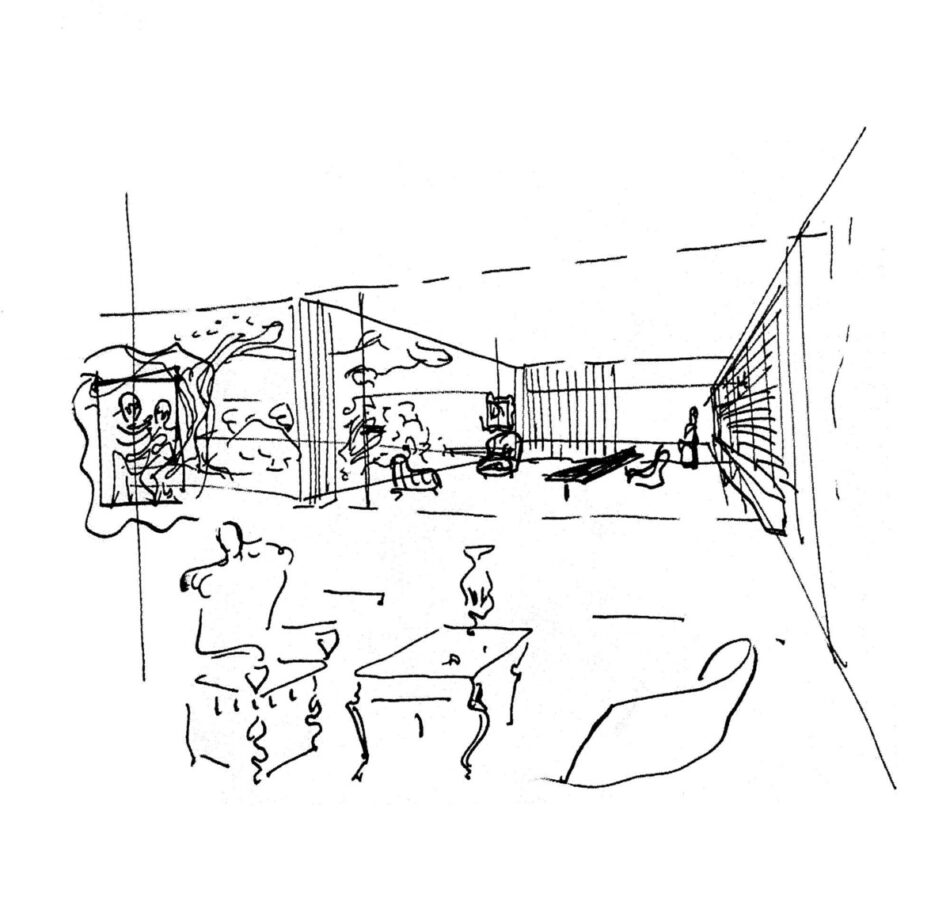

In the interior, columns are kept to a minimum, and glass walls hang like impalpable curtains, barely suggesting closure. Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion comes to mind, with its attenuated cruciform columns and low, reticent furniture, sited at artful intervals to avoid arresting the flow of space. So does his Tugendhat House (1930), where vertical supports have withdrawn entirely, leaving nothing but a formalist slab of horizontal space, extending endlessly into the distance. Bo Bardi’s glass walls also evoke—in our day—the transparency of Mies’s Farnsworth House and Philip Johnson’s Glass House, which were completed at about the same time. Nevertheless, unlike her counterparts in North America, Bo Bardi has yet to be acknowledged as one of the precursors of this typology.

Despite Bo Bardi’s obvious debt to her peers, the final result was very much her own. When filled with the couple’s huge art collection, the interior acquired a “lived-in” quality that differs markedly from the lapidary elegance of Mies’s minimalist approach, or the more tolerant interiors of Le Corbusier, with their eclectic mixture of art and mass-produced objects. One of the problems with purely essentialist conceptions of architecture is that they always ignore use.18 In this case, there was no “suppression of domesticity.”19 Space is subservient to place making. While Bo Bardi never acknowledged the influence of gender in her work, women’s greater familiarity with domesticity, and perhaps also her early training at Domus, may have influenced her use of interior design to complicate, if not challenge, the spare aesthetic of the architecture.20

The influence of both Le Corbusier and Mies can also be seen in Bo Bardi’s exquisite preparatory drawings. If the sketches are Miesian in their reverent attention to the boundless abstraction of space, they are tempered by the playful, meandering line of Le Corbusier. Her treatment of the human form brings to mind the fluid, sensuous line of Picasso and perhaps Matisse. Bo Bardi was never a mere epigonic figure: she was a consummate draftsman, and the sketches for the glass house can be counted among her best.

The rectangular plan of the main floor is organized around two garden courts. Since the house is built on the sloping crest of a hill, the vegetation of the first, perfectly square court is actually situated on the ground floor below. Trees and foliage irrupt into the vast open space of the living room, dramatizing the huge, loftlike area that takes up almost half the house. Seen from within, fronds and plants seem to hang, airborne, around the living room, their roots invisible from the second floor. The second garden is less ornamental and acts as a buffer separating served and servant spaces. On one side, the long rectangular courtyard brings light to the main bedrooms; on the opposite side, a blank wall cuts off the servants’ quarters from the rest of the house. Their windows have no views to the interior garden. While the front of the house is transparent and cantilevered, the bedrooms and the service wing to the rear are firmly rooted to the hill and defined by thick load-bearing walls.21 Bo Bardi plays off the opacity of the rear against the delicate glass treatment of the front. Some critics have seen this dichotomy as an attempt to separate night and day spaces.22 But the master bedrooms are hidden in the core of the house, while the service rooms are clearly visible from the exterior.23 In plan and elevation, the house clearly reflects the class stratifications typical of its day.

In the interior, Bo Bardi managed to differentiate the parts, avoiding the uniformity of vast open plans. Both the small garden and the staircase partition the space of the living room, so that the dining area at one end and the library at the other are given a certain seclusion. A similar role is assigned to the fireplace, an old-world typology infrequent in Brazilian townhouses. Furniture and architecture are perfectly integrated. Mindful of the need to balance variety with unity, Bo Bardi used color to punctuate and discreetly control the joyous cacophony of the interior, crammed with works of art and household plants: the tubular furniture she designed for the house matches the color of the steel frame, so that its bluish-gray hue resonates throughout the living-room. Blue mosaic floors were used to the same effect and echo the color of the structural supports.

The library is reminiscent of the larger one that Bo Bardi would later build for the art museum of São Paulo. An elegant steel frame with glass shelves, carefully proportioned to the larger mesh of the overall structure, enfolds the area in its spare, reticulated grid. On this side of the house, the ground slopes steeply away; there is no foliage to screen the books, and sunlight must have been a constant hazard. In this youthful work with an occasional touch of dogmatism, Bo Bardi’s elegant formalism sometimes overrode function.

Conceived as a bridge between the main spaces and the servants’ quarters, the kitchen looks out onto the forest, cut off from the long courtyard by a blind wall. Beautifully detailed and suffused with sunlight, the kitchen was full of timesaving devices unusual at the time: a garbage disposal, ironing machines, folding tables, and collapsible ironing boards.24 Bo Bardi chose black tiles for the floor and white tiles for the rest of the kitchen, but the masonry walls surrounding the windows are painted a bright green to match the color of the vegetation outside—a touch that showed unusual care in a room used exclusively by the house staff. If class was clearly inscribed in plan and elevation, it must be said that the quarters allocated to service were far in advance of prevailing standards. Servants—maids presumably—were given an apartment of their own, with bedrooms, living room, and a large veranda.

Although Bo Bardi experimented with mass-produced, stackable furniture and tubular steel, she was careful to soften any Taylorized, high-tech elements with natural-looking colors and materials—plywood, hemp, leather, and fabric. Contrast was her guiding principle here. The post-and-lintel rationalism of the architecture coexists casually with Baroque statues and heavy Renaissance cassoni, and these with popular culture and colonial artifacts. Exquisite art nouveau vases sit near crude earthenware pots from Northeastern Brazil, in an easy familiarity that reenacts the history of the new world. The Glass House was an immigrant’s home, harboring the couple’s cherished Italian heritage, as well as works from their new homeland. Perhaps only the weight of the past, which grounded and sustained their identity, permitted them to flourish in their adoptive country. Their beautiful glass home was a museum for living in. In this respect, it is interesting to compare the Glass House to Bo Bardi’s second and greatest project, the Art Museum of São Paulo, with which it overlapped culturally and psychologically. Despite differences in scale and destination, both share several typological traits, which should be studied in relation to each other, even though the museum can be dealt with only cursorily here.

The Art Museum of São Paulo

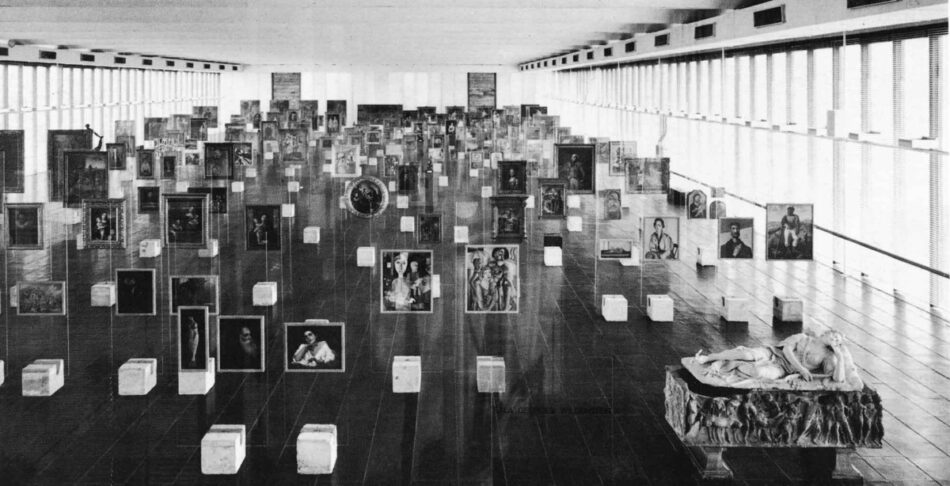

Commissioned by its director Pietro Maria Bardi in 1957 and completed in 1968, the Art Museum of São Paulo (MASP) was meant to be both a museum of fine arts and an exhibition gallery for contemporary art.25 Old master paintings are housed in an immense glass box contained between two thin slabs of concrete and cantilevered high above the ground. Bo Bardi strained the coefficients of safety to the utmost. With its clear span of seventy meters, the museum resembles a giant dirigible moored to the ground by two huge trusses painted bright red and rising from two pools of water. It is a daring structure. Bo imparts a sense of weightlessness to the whole, defying the gravitational pull of mass.26

Part of the sense of urban drama generated by the museum comes from its location. MASP is spectacularly sited parallel to the Avenida Paulista, São Paulo’s equivalent of Fifth Avenue, but perpendicular to the Nove de Julho, a multilane thoroughfare that cuts under the Paulista, a hundred feet or so below the museum: a void straddling another void far below. The rest of the building, not visible from the avenue, stretches beneath the free span and encompasses the spaces allocated to changing exhibitions, contemporary art, and the auditorium. It too is made up of glass walls between concrete floors fringed with greenery.

If the analogies to the Glass House are too obvious to require comment, the differences deserve to be stressed, for they shed light on Bo Bardi’s political and intellectual trajectory in the intervening years. Before embarking on this project, she had spent five years working and teaching in Salvador, Bahia,27 the heartland of Afro-Brazilian culture, which she tried so much to promote. She used the opportunity to explore the Northeast, an area extremely poor in resources but rich in native traditions, and to gain firsthand knowledge of the vernacular that few Brazilian architects of her privileged condition could claim. Her diaries and notebooks are full of sketches drawn from everyday life: crude furniture, market stalls, rudimentary shacks: “I made the most of my experience of five years in the Northeast of Brazil, a lesson of popular experience, not as folkloric romanticism but as an experiment in simplification.”28 Confrontation with the Brazilian hinterland brought about a major shift in her politics as well as her aesthetics. Bo Bardi’s commitment to the underprivileged dates from her experience in Bahia, which she once described as her “anthropological quest.”29 After her years in Salvador, Bo Bardi shed some of the polish that characterized the Glass House—the Miesian love of vitrified materials, dematerialized surfaces, fastidiously overdesigned detailing: “By means of a popular experiment I arrived at what might be called Poor Architecture. I insist, not from the ethical point of view. I feel that in the São Paulo Art Museum I eliminated all the cultural snobbery so dearly beloved by the intellectuals (and today’s architects), opting for direct, raw solutions.”30 At MASP, concrete is left in the rough. Industrial black rubber covers the floor. Everything is exposed: air ducts, plumbing, the elevator in its glass shaft. Transparency has acquired a new, transitive meaning, a sort of reciprocity, more appropriate to a collective building than to a private one like the Glass House, as the museum opens itself up to the scrutiny of the city and in turn becomes a huge belvedere. Color—the bright red—makes a striking appearance in her work, giving it a sense of the festiveness she associated with Brazilian architecture.31

It would be naive, however, to see Bo Bardi’s new direction as prompted exclusively by her experience in the Northeast. If she looked to the vernacular, she did so from a cosmopolitan perspective. MASP shows how attentive she was to contemporary trends in art and architecture; the growing importance of concrete, bold use of color, and reliance on “poor” materials were not unrelated to experiments overseas. But Bo Bardi had gained enormously in self-confidence in the intervening years and did not need input from others to shape her vision. She was no longer content to design a European building on Brazilian soil.

Yet the Old World is still present. Critics have generally overlooked the importance of Bo Bardi’s early use of glass. Her first two projects, boldly cantilevered, dramatize the utopian, incorporeal aspect of this material. In the museum’s interior, paintings hung from glass panels, so that on arrival the visitor saw dozens of overlapping panes of glass at right angles to the longitudinal glass walls. (In recent years, the interior has been shamelessly changed by an unsympathetic administration.) This mystique of glass, which would disappear from her later work, may owe something to her husband, who was fascinated with the material. From 1938 to 1943, Bardi had directed the magazine Il Vetro (Glass). He also reconstructed the history of glass in Italy in a book he published in 1940.32 It was Bardi who gave Lina Bo the two commissions that launched her career. His importance as both interlocutor and client can hardly be overestimated.

On the other hand, the money and the initiative behind the museum came from the controversial Assis Chateaubriand, who was ultimately the patron. Even though Bo Bardi was moving away from the sleek sophistication of her first project both formally and politically, Chateaubriand was a throwback to those authoritarian personalities familiar to the Bardis from their Italian days—men for whom the ends justify the means, and with whom they were increasingly impatient.33 Whether her growing incompatibility with these older, autocratic models was clear to her at the time remains open to question, but in the years to come, and especially after the military coup of 1964, Bo Bardi would work for clients of a very different sort.34

The Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

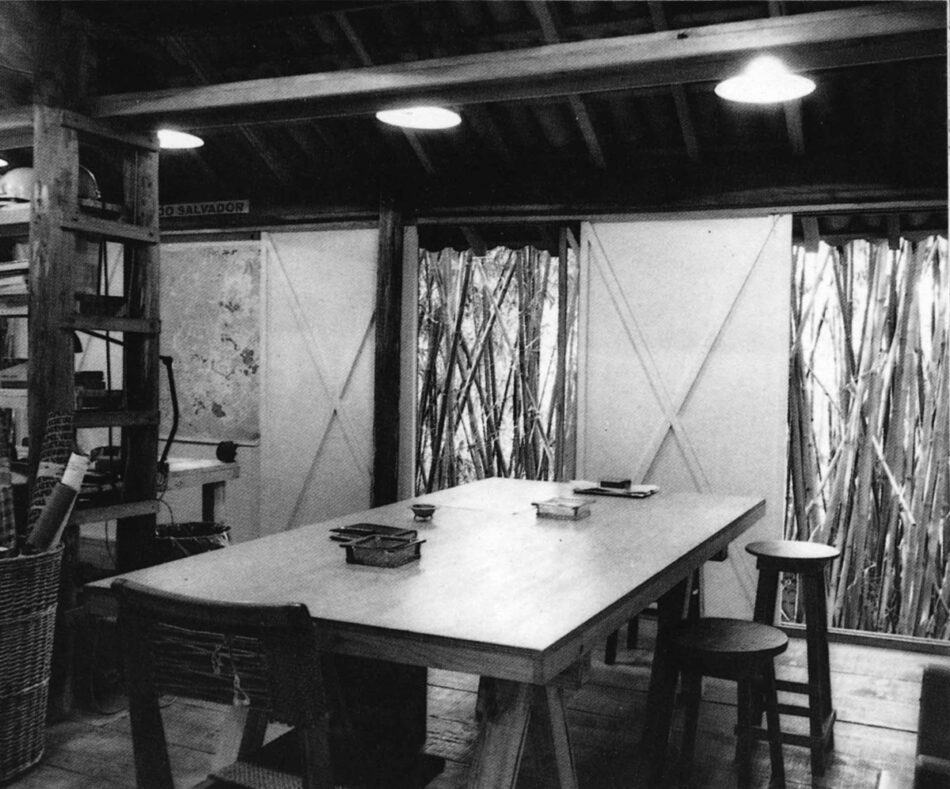

Any analysis of the Glass House must take into consideration one last building: the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi, erected at the back of the residence almost thirty years later, in 1986.35 It shelters the nonprofit organization dedicated to Brazilian culture founded by the couple. The building sits companionably in an environment grown familiar to Bo Bardi over the years. Unlike its elegant glass neighbor, it does not reflect the attitude of an exile. Designed with her collaborators André Vainer and Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz, the diminutive structure is like a gentle postscript by that other, older Lina Bo, who had become a specialist in the Brazilian vernaculars. These taught her that the relationship between architecture and nature need not be based on contrast and competition. Cued by the environment, she rejects the use of nature as a foil, relying instead on a mimetic interplay with the surroundings. For this tiny building, hidden by a tangled skein of thick vegetation and a bamboo grove, Bo Bardi chose nonauratic, homespun materials: traditional tiles for the roof, wooden planks for the floor, and wooden bracing on the exterior. Only the nylon sliding doors allude to the urban and the modern, recalling the Japanese influence prevalent in São Paulo.36

New materials call for new codes of representation. The short, stocky pilotis that prop up the little house make no reference to Le Corbusier. Earthbound and empirical, architecture is here reinterpreted by a practitioner who no longer professes the puritanical and renunciatory ethos of high modernism, nor the adversarial relation between high and low on which it is predicated. An almost totemic respect for nature overrides the cerebral geometries of the avant-garde. Nevertheless, this is no “primitive hut,” haunted by the myth of the noble savage, but a research institute for urban sophisticates in which the architect opted for a new formal idiom, soft-spoken rather than declarative, low- rather than high-tech. As the years passed, Bo Bardi abandoned the inhibition of the language of the body, one of the touchstones of high modernism. Most of the architecture is here routed through the body, a lesson no doubt fostered by her acute understanding of vernacular culture. Vision alone can no longer vouchsafe the sense of immediacy afforded by touch. Unlike the Glass House, in which every detail is flexed taut, there is a softness here, a willingness to relinquish control. By using “anti-eternal” materials, as she put it, the structure becomes vulnerable to time.37 Side by side, the institute and the Glass House—the raw and the cooked, the South and the North—underscore the long odyssey undertaken by Lina Bo Bardi, whose work has been aptly described as a “complex mosaic of quotations from the most erudite to the most everyday and popular, joined together in a personal manner by a greater eclectic sensitivity.”38

But Bo Bardi was no lapsed modernist. Even when designing with wood and thatch, she never lost her interest in the avant-garde and continued to curate remarkable exhibitions of modern art in both São Paulo and Bahia. However much her practice may have changed over the years, her support of modern architecture did not waver. She never abjured in print the Corbusian gospel from which her work increasingly distanced itself. That is, the early Corbusian gospel: the later, sculptural work of the master impressed her far less than the heroic projects of the late ’20s and ’30s, with their vitalist rhetoric and messianic conception of the architect. “Compared to the previous revolutionary creations,” she wrote of his contemporaneous work, “the church at Ronchamp is a Mediterranean retrenchment after the manner of Ponti and Rudofsky.”39 The Bardis had been active participants in the great battle for modern architecture in Italy, and never quite lost their militancy and combative stance.40

In the end, Bo Bardi remained European, though perhaps her architecture did not. Her capacity to see things anew—from the lowly and raucous to the elegant and ethereal—and her unwillingness to take anything for granted gave her a critical distance that marked her as different. But the receding Italian past left lingering traces. Over the years, she cast off one by one the spoils of a profession grown distant and overcultivated. One has only to look beyond the liveliness of her wonderful sketches, so joyous and full of humor, to find the sense of dispossession that characterizes her late work, a hunger for the irreducible and the primordial. The quest that led from the Glass House to the willful solecisms of the little wooden institute stemmed neither from a retrenchment nor from a search for origins, but from what one critic has identified as a “profound sense of bereavement.”41 Perhaps this is what Bo Bardi implied when she once described Brazilian architecture after the war as “a light shining in a field of death.”42 Perhaps the past was not in abeyance after all, even after so many years: a contemporary dictatorship could not help but evoke another, awakening old fears and opening old wounds.43

Gender

Like many women architects of her time who succeeded in breaking into a profession that is still a male preserve, Lina Bo Bardi used her opportunities to advance the cause of humanity rather than the cause of women. In fact, she had very little to say about women, and occasionally dismissed them with the same depreciative attitude as her male colleagues, whose parameters she internalized.44 Not a single woman can be found among the list of her collaborators. Like Charlotte Perriand, Lilly Reich, and so many others, Bo Bardi was content to be one of the boys and usually appears in photographs surrounded by men, often well-known intellectuals (Albert Camus, Glauber Rocha, Gilberto Gil).45 Nevertheless, the fact that women architects of her day sometimes identified with men seems to have given them a psychological beachhead from which they could operate in a position of power rather than of victimization.46 What constituted “identity” was negotiated according to need: one could assume stereotypical gender roles at home and radically different ones at work.

Did gender have an impact on Bo Bardi’s work? Undoubtedly. She may have built more than other women architects, but she was given fewer important commissions than her male peers in Brazil. Although she was never marginalized, her far-flung oeuvre, and its diversity of style, scale, patronage, and destination, were definitely linked to a lack of “mainstream” opportunities: “I have architectural inhibitions. It isn’t a pose, it’s a sickness: I am unable to design a Bank, a mansion, a Hotel. I would have loved to have been called to design maybe a Hospital, Schools, ‘Popular’ Houses, but it never happened.”47 She made a virtue of necessity, fully embracing new vocabularies and political agendas that she might otherwise have ignored.

We cannot judge Bo Bardi by the standards of a different age. For women of her generation, the important thing was to build, and she did so, against all odds, with tenacity, skill, and extraordinary originality. From the Glass House on, she managed to hold her own in response to both the post-and-lintel rationalism of CIAM and the plastic lyricism of the Brazilians. Rejecting the grand redemptive gestures of Niemeyer’s work with its sculptural exteriors and free-flowing interiors, she embraced commissions that precluded a signature style: parishes for poor congregations, community centers for factory workers, work for film and theater, and historic preservation.48 In this respect, the Art Museum of São Paulo proved to be an exception in a career marked by a growing commitment to the underprivileged: “One cannot operate legitimately in the absence of a well-determined political structure, a political structure that is grounded in the bedrock of social justice.”49 What distinguishes her work radically from that of equally famous counterparts like Lúcio Costa, Affonso Reidy, or even a professed communist like Niemeyer is not only gender and style but above all political praxis: the kind of projects she accepted, and the issues of patronage, technology, and typology that they implied. Convinced that “everything that can make misery bearable should be destroyed,” Lina Bo Bardi placed political engagement above identity politics.

Ultimately, what matters is not her attitude toward women but ours, and our purpose in writing about her work. The goal, as Linda Nochlin once pointed out, should not be to enrich the canon by recuperating forgotten or underestimated figures, but to question the ideological process that excluded them, by “reading them, and often reading them against the grain.”50 Bo Bardi’s oeuvre testifies to the passion with which she challenged her profession, her colleagues, and her own past. We owe her work no less.

Epilogue

Years ago, when I was an undergraduate, I was invited to the Glass House. Pietro Maria Bardi ushered me into his study. While he was showing me drawings by Le Corbusier from his archives, Lina Bo Bardi came in unobtrusively to serve coffee on a silver tray. Her husband called my attention to the silverware by Jean Puiforcat. Bo Bardi just smiled and left as quietly as she had entered, probably to produce one of those astonishing designs that so move me today.51

I want to thank Mary McLeod, whose many suggestions did much to improve this text, as well as the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi, for photographic materials.

Esther da Costa Meyer is an assistant professor in the department of art and archaeology at Princeton University and the author of The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future.