Building to Extremes: The Architectural Invention of OJT

One balmy New Orleans afternoon in 2015, as the sun went down and the local bars hosted oyster happy hours, architect Jonathan Tate was closing up his Lower Garden District storefront office. Up pulled a scruffy-looking man who locked his bike at the curb and opened the door. “I’m looking for Jonathan Tate. I need the smallest house possible,” the man proclaimed.

The mysterious wayfarer was Michael Burnside, a retired army veteran and former physics professor who had just bought a tiny lot in Central City. Tate eventually helped develop the smallest house in New Orleans for Burnside, who lived on-site in a makeshift tent in the lumber pile for two years during construction. Using only hand tools, Burnside siphoned power from a generous neighbor’s extension cord. The house is finished in a beige color that the local paint store makes from leftover paint. “We are really proud that it’s the ugliest house in New Orleans,” Tate says. “You can’t tell it is architecturally significant at all.”

Burnside’s extreme resourcefulness and opportunism made him a perfect fit for the work of Office Jonathan Tate (OJT). The firm has made its name by investigating real estate development and manipulating the financial and political circumstances in which architecture takes place. Their unique approach allows them to exert more control over the process and to deliver buildings that reflect the policy and finances they are working with. To support this nontraditional practice, OJT produces work that is radically different from the instruments of service that architects are ordinarily contractually bound to deliver: end-user instruction manuals, innovative policies, win-win financial products, and perhaps the most nontraditional architectural output: buildings.

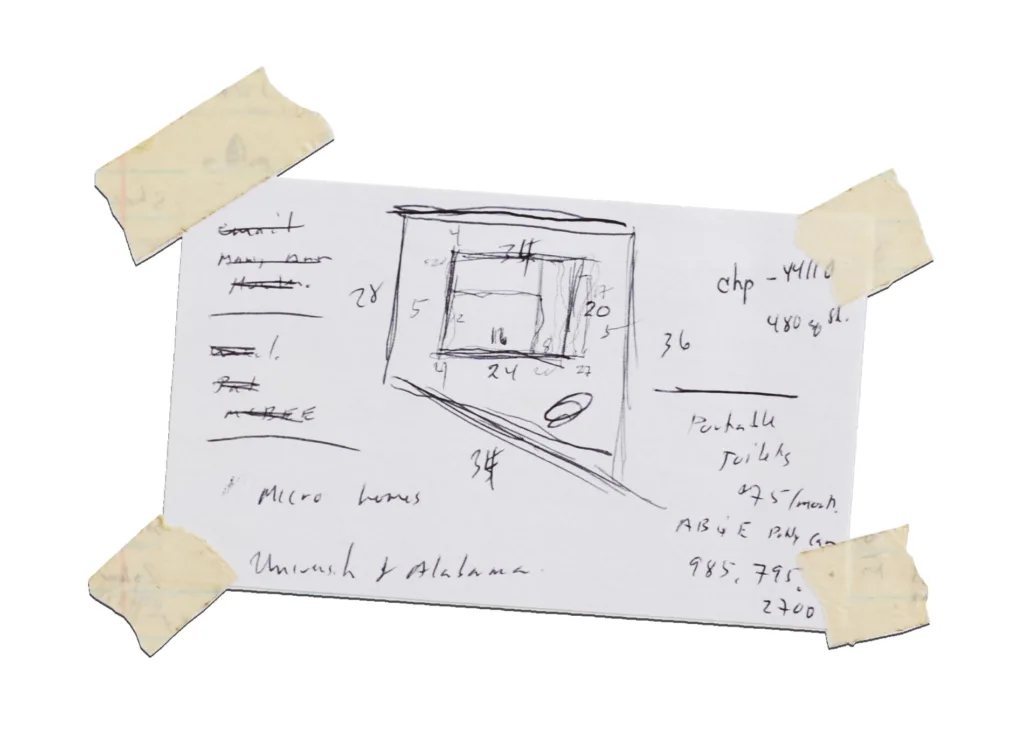

“Felicity,” Michael Burnside residence, sketch, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2015.

“Felicity,” exterior. Photo Will Crocker.

OFFICE OF JONATHAN TATE

Originally from Madison, Alabama, Tate attended Auburn University where he worked at Samuel Mockbee’s Rural Studio. “Some of the broader objectives of the studio—like social goals, community, actively propagating work, and architecture as a different form of service—have found a place in the work we do now,” he says. After 10 years in Memphis and graduate school at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Tate moved to New Orleans in 2008, invigorated by the opportunity to join the city’s post‒Hurricane Katrina reconstruction efforts.

As a young architect, Tate was eager to build. Rather than wait for clients or institutions to approach him with work, he went out and created it for himself. Starter Home* is a series of speculative infill housing projects that Tate describes as an “opportunistic urban housing program.” Using scripts and geographic information system (GIS) data, OJT identified 5,453 small, nonconforming “odd lots” that builders and developers might not see as desirable. For their first project, at 3106 St. Thomas—a 16-and-a-half-foot-wide lot in the Irish Channel neighborhood of New Orleans—Starter Home* financed, designed, and built a 40-foot-tall metal-clad single-family home with a diagonal roof that riffs on the vernacular architecture of the historic context.

St. Thomas and Ninth, New Orleans, 2017. Photo Will Crocker.

The success of that first house led to 16 more using this model, including a 12-home development at St. Thomas and Ninth Streets in New Orleans, built as-of-right with no variances to the existing code. The ten single-family homes and two two-family homes on the site are all separate volumes, so they adhere to single-family zoning under the law but leverage the density of multifamily housing. The resulting design is legible as a cluster of detached homes (albeit with very small distances between), a diagrammatic form that expresses the particularities of the zoning and OJT’s response.

The first Starter Home* won a 2018 AIA National Housing Award, while the 12-house development won a 2019 AIA National Honor Award. Building on this success, Tate crowdfunded $95,000 to build two more houses on an odd lot on S. Saratoga St. in Milan, a transitioning, inner-city neighborhood of New Orleans. With 8 percent annual return and a 30 percent profit share, the 36 investors were fully paid back. In fact, collective financing would become an important tactic for OJT, along with the other clever development tools that evolved from the Starter Home* project.

Their overall body of work earned OJT a selection as a 2017 Emerging Voice from the Architectural League of New York. League program director Anne Rieselbach explains, “The jury was impressed by the inventive small-scale housing that truly demonstrated an economy of means. They are carefully composed and materially ingenious, even given their small budgets, and challenging and frequently irregular sites. Despite these myriad constraints, the firm’s focus on understanding and interpreting places produced contextually harmonious designs.”

SOME CLARIFICATIONS

There are many terms that Tate avoids. “Tiny homes” is one. “These aren’t tiny homes, they are family homes,” he makes sure to point out. “Prototype” is another. “The houses themselves are not prototypes. They each illustrate a research and community development model that can evolve and allows for input from users or a community. Each is unique to its site.”

And perhaps most provocatively, Tate does not consider himself a developer. “We aren’t developers. We are architects that occasionally develop things,” he says. “Develop-ment is a tool for us to continue to explore an idea, and to illustrate imaginative ways to work within markets, rules, and regulations.”

Architects often take a passive role in the market—simply delivering a service for a client, resulting in lackluster housing, office buildings, and retail and commercial projects. Of course, the architect also takes on less risk in this traditional model. The client assumes the risk, but in turn makes the decisions about who the building is for, where it will be, and its directive and purpose. The architect simply designs. OJT’s practice attempts to overcome this bifurcation.

There are two models of practice in which the architect’s responsibilities are coupled with other roles. The first is the architect-developer: they control the process on the front-end, assuming the role of client (developer) to take on the ideation, programming, scope development, and financial burden. Tate’s desire to build is what started him down the path, but he does not want to be the client—a key distinction between OJT and an architect-developer. “We want to own more of the process, but ultimately we are not the client,” he says. “We want to work with other people to make their own vision a reality, which is really what makes architecture so rich.”

3106 St. Thomas, New Orleans, 2014. Photo Will Crocker

St. Thomas and Ninth, exterior. Photo Will Crocker.

The second model of practice is the design-build firm, which couples architectural services with the role of the contractor. Pioneered in the 1970s, design-build is a standard form of practice today and has been widely adopted. But Tate argues that in both architect-developer and design-build models, the financial risk of either the developer or contractor simply overwhelms the project, and as a result architects fall back into normative modes of practice. “The model eventually gets codified, replicated, and loses its criticality in turn,” he says.

While Tate and his colleagues use some of the tactics of both of these models of practice, they see themselves as different in several ways, especially in how they take on risk as the client to set the terms of the project before the design phase. They describe the traditional role of the architect as “in-between—and apart from—two very critical components that create our built environment: the conception, including the economics of a project (the ‘front-end’), and its construction (the ‘back-end’).”

OJT, on the other hand, takes on both the front-end and back-end risk of the project. Front-end risk entails financing, program, site, audience, and other factors that define what the project is. Back-end risk is what comes after design, including construction, management, insurance, operations, and sales. By taking on both front-end and back-end risk (from conception to completion), OJT is a more active participant in the delivery of a building. The disciplinary diversity of the practice—which means OJT acts as planners, community advocates, developers, and builders—makes it resilient, relevant, and consistent with the expertise architects have.

“Having a passive role in the housing market was something we were uncomfortable with,” Tate says. “Ultimately, by manipulating and toying with the natural tendencies of development like zoning and land use, instead of resisting them, you could actually do a lot of great work.”

CLARKSDALE AT A CROSSROADS

Using the strategies and tactics formulated in New Orleans, OJT has begun to develop similar projects in various typologies, different formats, and at a variety of scales. The firm embarked on a hotel project in Clarksdale, Mississippi, for example. The town has seen significant population decline and suffers from myriad racial and economic issues. Located at the crossroads of US-49 and US-61, however, it is also the epicenter of blues music, where blues legend Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his supernatural music ability.

Inspired by a collective artists’ housing model they’d read about in The New York Times, OJT renovated a 1920s building into the Travelers Hotel, a boutique property that employs artists in exchange for housing. Owned and operated by OJT, with partners including local arts advocacy nonprofit Coahoma Collective, this live/work artist residency program attracts talent from around the country to Clarksdale’s downtown. The site was defined by OJT and their collaborators, using a matrix of program, costs, time of construction, and land. The adaptive reuse has a light touch, leaving much of the roughness of the original structure while making strategic insertions to bring it up to standard and using the hotel model to maintain affordability.

St. Thomas and Ninth, aerial. Photo Will Crocker.

The project was the beginning of a citywide project to revitalize Clarksdale and leverage its unique history and culture as a catalyst for positive change. “We asked ourselves, ‘What does it take to insert ourselves in the place?’” Tate says. “And what is the built environment’s role in bringing somewhere back?”

The project spun off into several other projects—some client-based and some self initiated— including trails, art installations, a nascent housing trust, and a riverfront redevelopment. OJT also developed Clarksdale Collegiate Public Charter School in an old church that had a shrinking congregation. The church sold its building to the school and the congregation merged with another aging church across town.

In areas with lower land prices, developing a site can be easier on the front end, but making it economically sustainable is harder since there isn’t the same base of customers and buyers. “We’re always thinking about what land means for these places where real estate isn’t as overheated,” Tate says. “The fun part is asking, ‘How can we provide value?’” Tate said. “[In New Orleans], post-Katrina, if you proposed something, people were happy and would help you and not get in the way. Clarksdale is still like that.”

Working in rural areas of the South has garnered the attention of others working to create a lasting impact in these regions. “OJT inventively takes an urban site and translates it into an architectural form that is very much of the place, but is still unique and part of the current discourse,” architect and fellow Auburn alum Marlon Blackwell says. “They elevate form, materials, details, and vernacular to both honor and transcend the place. Their work all has a really authentic vibe to it.”

NEW POLICY MODELS

More recently, OJT worked with Memphis Medical District Collaborative (MMDC), a group striving to densify and create infill housing in neighborhoods around the hospital. In 2023, OJT created Form Book (like a Sears catalog), which includes five home designs: a single family, an accessory dwelling unit (ADU), a duplex, a quad, and a multifamily. Like OJT’s Starter Home*, Form Book is designed to expedite the process and give developers a turnkey solution for building homes.

“We wanted to do the same thing OJT did in New Orleans—to unlock land and create a vernacular that would be responsive to the communities, but also create a new contemporary typology,” says Ben Schulman, who worked with OJT at MMDC. “What is fascinating about Tate’s work is that it is sensitive and rooted in the design dynamics of the place, but also he understands that form follows finance, including reading the code and the social and historical dynamics of the site.” Four of the five types of houses shown in Form Book are now in some degree of development.

4514 S. Saratoga, New Orleans, 2015. Photo Will Crocker.

OJT has also undertaken a similar housing experiment to develop “Missing Middle Infill Housing” for the city of Chicago. Here, a “kit of parts” strategy can provide adaptive responses and create single-family homes that “jumpstart generational wealth through homeownership and rental income opportunities.” Rather than a concern with a particular aesthetic, it is a system designed to be leveraged to fit a variety of sites throughout Chicago.

Increasingly sophisticated, OJT’s pragmatic projects all ask similar questions about how to better intervene in the development process that is particular to each site, its protocols, and its systems of funding and regulation. Constant reinvention and investigation is what keeps the practitioners engaged with their work, even when they are in unfamiliar territory. “Every day we ask ourselves, ‘What exactly are we doing?’” Tate joked.

OJT’s practice and what they produce—their instruments of service—might be the antithesis of a typical architect. Traditional firms produce drawings, models, and written specifications that lead to buildings by describing the construction process. Inversely, OJT produces buildings that describe the rethinking of the development process. The results—buildings—are not prototypes of products, but rather act as repeatable models for how to achieve agency in the murky waters of contemporary urban development, politics, and finance.