Core Sample

When asked to be the guest editor for this issue of Harvard Design Magazine, I was intrigued by the title “Landscape Architecture’s Core?” as it opened up a question—an invitation to enter an exploration into the “core” of the discipline as it continues to evolve, deepen, and diversify.

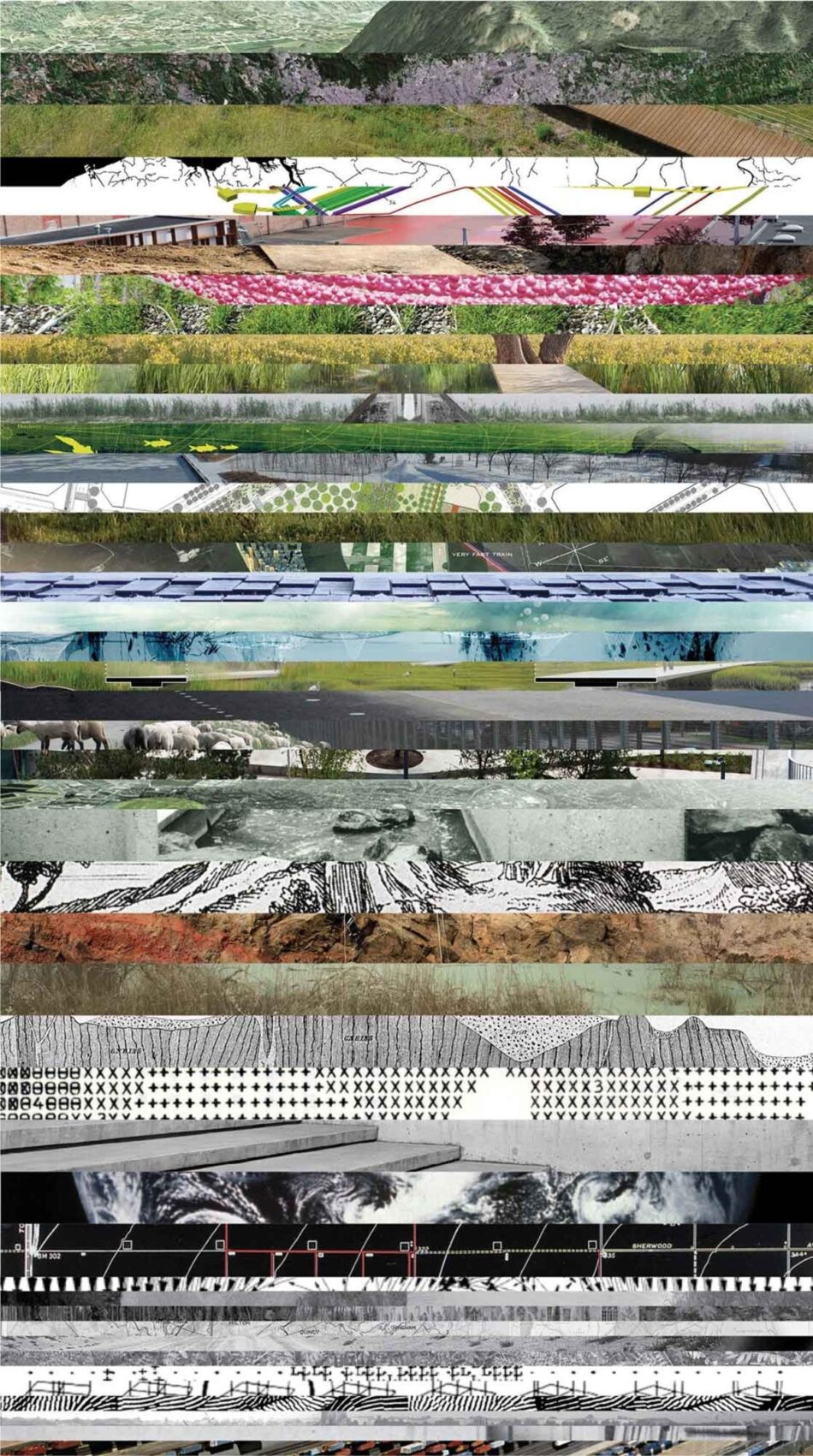

Here, the core sample offered a relevant framework: A process where a study area is identified, an auger is driven into the ground, and a sample of material is removed to be analyzed for its physical makeup, its essential elements.

After a series of discussions with Harvard GSD faculty, landscape critics, theorists, and practitioners, it quickly became clear that in identifying the study area, the target should not be to define the “core” of the discipline, but to define the discipline itself. What is landscape architecture and what is not? Where are the boundaries of the field? What scales and territories of engagement fall within “landscape architecture” and which do not? This survey of the breadth and depth of the discipline, allows us to identify an entry point—a representative sample of the field—through which we can extract and analyze the essential elements.

With this in mind, the introductory sequence of essays sets out to define the operating territory of the discipline today, collating an assemblage of practices, operations, and ideas that we might call “landscape architecture”—how that has changed over time, and how that will continue to change in the future.

In “Immanent Landscape,” Christophe Girot challenges our assumptions about nature in the city as he navigates the line where “landscape ends and landscape architecture begins.” In “Landscape as Architecture,” Charles Waldheim traces the etymology of the name “landscape architecture” itself, and its relationship to the evolution of the urban commitments of the discipline. In the first of two photo essays, “Scales of Engagement,” we examine the immense range of scales that landscape architects engage in their research and practice. Progressing in scope from the texture of a leaf up to the spatial realities of climate change, these images challenge readers to zoom in (or sometimes out) to gauge what it is they are really looking at.

In “Territories of Engagement,” we discuss questions of scale, approach, and tools of design through conversations with a selection of design practices around the world. This collection of ideas and images offers us a clearer picture of the broad operating territory of contemporary landscape architecture and the ongoing thickening of the field. Critic Ian Hamilton Thompson takes this exploration one step further in “Essence-less Landscape Architecture and its Extended Family” as he combs the boundaries of contemporary practice in search of “family resemblances”—loose clusters of approaches to landscape architecture that reveal not necessarily an “essence” but “a network of overlapping but discontinuous similarities.”

A survey of ideas and practices found within this defined territory begins to reveal patterns in the types of questions that landscape architects (practitioners, critics, and theorists) are engaging in their work and, if we look back, have been considering since before the discipline formally emerged as modern-day landscape architecture. Each of the subsequent features in this issue reflect on contemporary expressions of these fundamental (or could we even say core?) questions for the discipline: the cultural role of the designed landscape; the relationship of landscape to time, dynamic processes, and layers of history; the ongoing tension between culture and nature in the constructed landscape; creating spaces with a palette of living (and dying) materials; engaging ephemeral phenomena; and perception of space and place.

In “Why Not Cultural Systems?” Charles A. Birnbaum examines the cultural value of the designed landscape: What is its role in the city? How can we measure its value? In “Envisioning Hyperlandscapes,” Sébastien Marot—in search of a new operating metaphor for landscape—questions the fundamental relationship of landscape architecture to site, meaning, and layers of time. This conversation about the essential relationship between landscape and time continues with “Shifting Landscapes In-Between Times,” as Jacky Bowring and Simon Swaffield grapple with the inevitable certainties and uncertainties of working with and within dynamic systems. Our second photo essay, “The Altered Landscape,” from the Nevada Museum of Art’s Altered Landscape Photography Collection, further questions this exchange of cultural structures with (and sometimes against) natural environments. This selection of images evocatively documents the effects of the Anthropocene era, where the impact of human alterations on the landscape has begun to surpass that of natural disasters. In the first of our two-part discussion on “Substance and Structure,” Jane Hutton examines “The Material Culture of Landscape Architecture,” describing the essential tectonics of structuring sites out of the earth and the temporal nature of living materials. In “The Digital Culture of Landscape Architecture,” Antoine Picon furthers this discussion through a critical look at the implications of the ongoing digitalization of the making of landscape. Finally, Günther Vogt and Mitchell Schwarzer address the fundamental questions of perception of space, phenomena, and experience that are embedded in both the designed and the natural landscape. In “Shadows of Landscape,” Vogt examines the cultural and conceptual challenges of spatial perception, while in “Landscape Navigator,” Schwarzer analyzes how that perception changes with physical modes (and speeds) of engagement with the landscape.

In the final sections of the magazine, we feature a selection of specific viewpoints on contemporary landscape practice. In “Conjectures,” Julia Czerniak takes a critical look at criticism (or the perceived lack of it) in landscape architecture today, and Frederick Steiner challenges us to move beyond sustainability as a goal for design. In “Books,” John Dixon Hunt treats us to a comparative review of more than twenty recent publications in landscape architecture revealing trends both in design publishing and in the discipline itself. A new section, “Excerpts,” features ongoing research, publications, and events at the Harvard GSD highlighting our engagement with these core questions of landscape architecture.

The question “Landscape Architecture’s Core?” has led us to the rich and diverse collection of work featured in this issue of Harvard Design Magazine. We hope you will enjoy it, question it, and be inspired by it as much as we have.