/

Designing at Knee Level

Mariana Ibañez

You both write, produce, and teach about technology’s effects and opportunities in the context of design and space-making practices. The design studio you taught at Harvard last year, “Robots In and Out of Buildings,” and the work you’re doing in robotics at your company Piaggio Fast Forward (PFF) seem to converge on the topic of mobility. Why mobility? And, considering the context of our conversation in a magazine issue on labor, how will developments in mobility impact the workplace?

Greg Lynn

Consider the railroad, Morse code, and telephone lines as a precedent. Information technology and physical mobility have always been paired, and over the last 20 years, information technology has moved very quickly. The workplace has changed not only because of smart devices or laptops, but also because of new kinds of mobility. Nearly every piece of furniture in an office—desks, chairs—has wheels on it; and today, things are getting smart enough to move by themselves. At PFF we are developing an interior/exterior mobile device called gita, which requires us to rethink the corporate work space as a site.

Jeffrey Schnapp

Thanks to the ubiquity of networks and mobile devices, indoor/outdoor divisions have shifted, presenting an opportunity for rethinking the workplace and its boundaries. This is the context within which we’re reconsidering the interplay of vehicles, buildings, furnishings, and fixed and mobile devices, not to mention exploring hybrid modes of action and interaction that characterize the contemporary workplace.

MI

Your work implies a design domain that works across scales from furniture to larger urban infrastructures of transportation. At the scale of furniture, the reliance on tools like the Knoll catalog, for example, has played a key role in giving form to the workplace and constructing the apparatus that supports labor. How can designers start imagining a new apparatus of labor? Do we need a new vocabulary for workplace design?

JS

One of the challenges of reimagining workplaces has to do with the relationship between screens as connective devices and other sorts of physical supports for work. The desktop’s absorption into the laptop and other smart devices has truncated a conversation about the advantages of distributing some of those functions. Instead, it unifies them within a single device that then becomes the portable “desktop” or “workplace.” Thinking about a more multisensorial model of work, rather than assuming that all tools and connective tissues have to be funneled through a single smart device and screen, is the beginning of that design conversation.

GL

There’s a whole ecology of stuff that you don’t think of as furniture but that actually functions like furniture. In our studio and seminar at Harvard, we started to inventory these devices. Then, at the building infrastructure scale, we asked how these devices influence vertical circulation. How do they change entry to the building? Do these devices and people move through the same corridors, or do we need another kind of corridor? Do building systems move around? Can you move the lights around?

JS

Is infrastructure now a programmable, mutable feature of a building’s daily, weekly, monthly, yearly cycles?

MI

The idea that everything is constantly changing will definitely put some pressure on architecture as we know it—particularly in terms of how it’s made and how it’s occupied. I want to bring up the issue of robots in the workplace versus robots as workforce. Many offices are being retrofitted with technology that assists human labor, making it faster or more secure, or automation technology that is replacing human labor altogether. The spatial implications of both are vastly different. To what extent is the architecture of labor still a human-occupied space?

JS

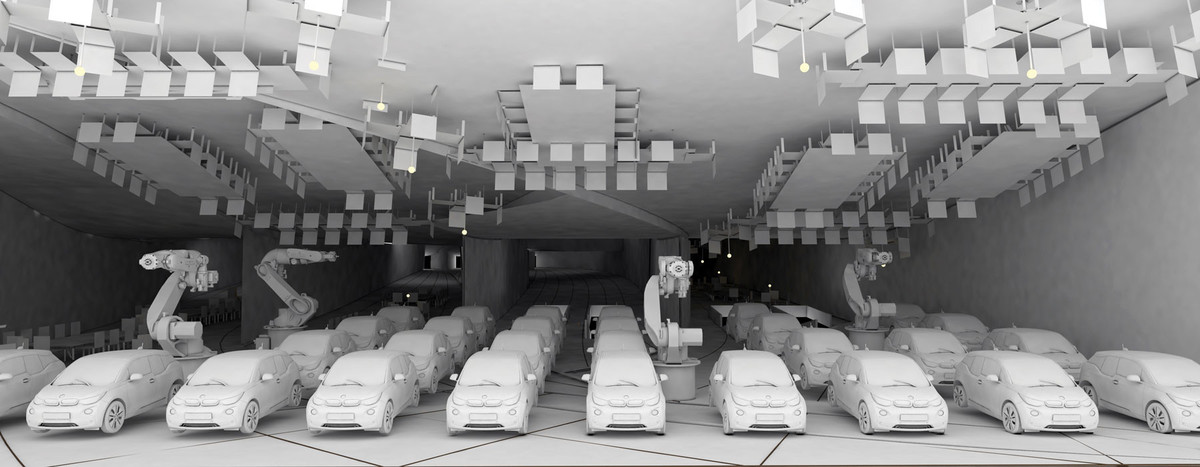

Of course, the answer to your question is different in different domains of labor. The kind of labor we were grappling with in the studio was essentially a white-collar, knowledge-economy model of production. Our case study was a variant on the Facebook headquarters, which is very different from the factory floor, where robotics has had a transformational impact on production flows, not to mention on the roles performed by humans. We’re exploring a workplace in which the labor is human-centric in ways that a factory is not.

GL

In an old-school way, we want to promote social interaction. We’ve thought about how much time people in offices spend looking at screens all day, and we want to offer an alternative. How do you get people to interact with each other directly?

MI

Should robots then disappear into the background?

JS

At PFF, our focus is on designing human-robot interactions that are so intuitive that you almost forget that you are interacting with a robot. The notion of the robotic agents as augmenting human capabilities is central to our design process, much as human augmentation was fundamental to the earlier history of electronic media and computation.

GL

These robots don’t have googly eyes. You’re not supposed to interact with them. They should be like your shoes. I don’t talk to my shoes and say, “Hey shoes, let’s go for a walk,” but I’m very conscious of my shoes every morning. I care what they will say about me and how they help me get done what needs to get done. We want robots to be part of your lifestyle, but not something you have to have a negotiation or a relationship with.

JS

Early on at PFF we committed ourselves to a nonhumanoid approach to designing robots. We strive to create smart robotic vehicles that move the way people do, and we try to make those interactions as direct as possible, eliminating the mediation of screens, limiting vocal cues, and using the sensing capabilities of the robot to track and perform advanced feats of navigation (even autonomous feats of navigation).

GL

If we personify products at all, it would be from a beast of burden perspective—almost as if the automobile was a mechanical horse. We want to learn how people move with stuff. But expressing that through a face or a style or a form? No. I have everybody in the design and software team reading Mark Rakatansky’s essay on Chuck Jones in Assemblage, because the personality should come from how the robot moves with people, not from anthropomorphization.

MI

Your students worked on designing the headquarters of a tech company. There are typically two types of design approaches to such buildings: new headquarters—think, Apple, Google, etc.—and the retrofitting of old buildings. Are new buildings for tech companies as revolutionary as the technologies the companies are producing? Are these projects transforming space making, or are they just symbols attached to technology?

GL

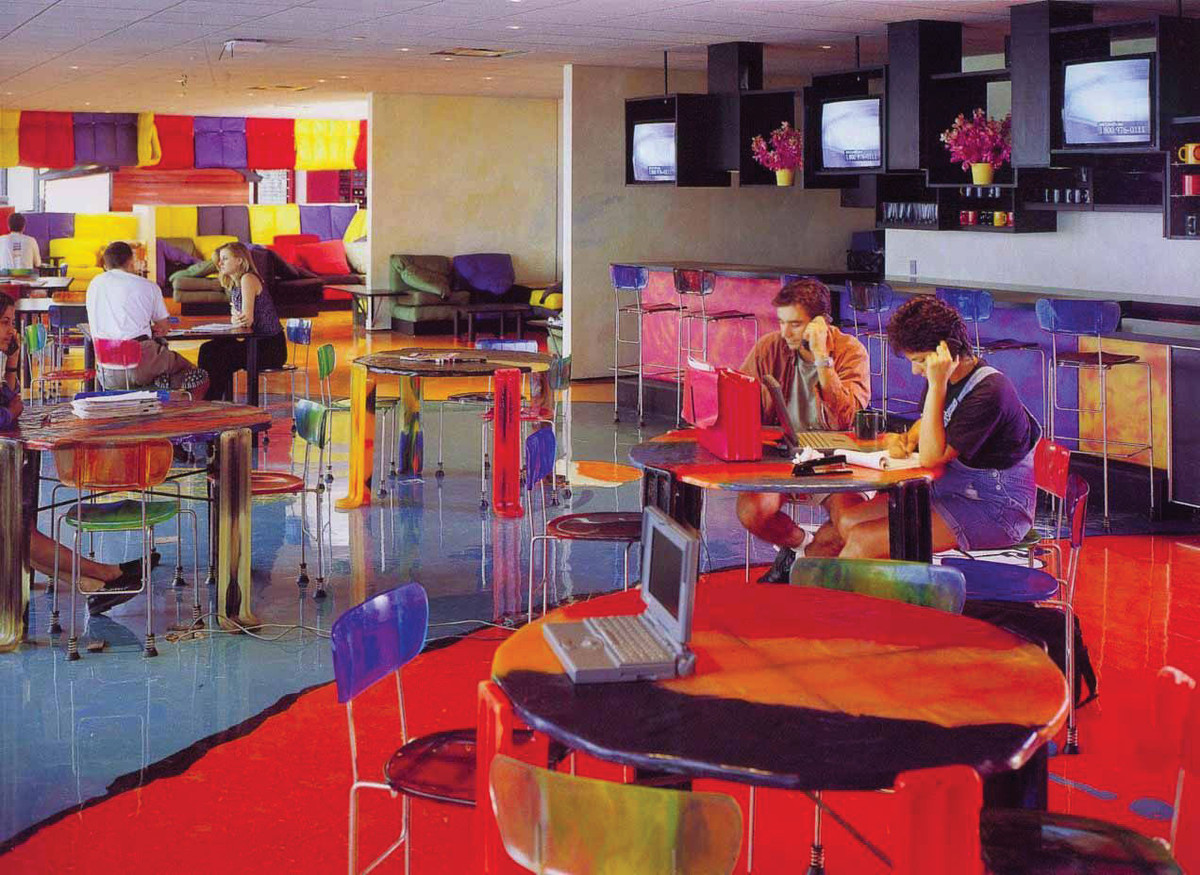

I don’t think you could ever separate those functions. Take, for instance, Gehry’s early Chiat/Day hot desk office spaces. It was probably Jay Chiat and Frank Gehry who came up with the idea of multiple workers using a single workstation in rotation, and the technology was just emerging to chase it. Laptops were emerging at the same time that the agency that ran Apple’s PR was in what we now call generically a “creative office” space—it was Chiat/Day that made the “Think Different” campaign for Apple. The market for a laptop computer coincided with the development of new architectural ideas and it’s a dynamic between the two and not a consequence of one from another. Architecture is background and atmosphere, but that doesn’t mean it is following technological innovations. Because it is background it rarely gets the credit it deserves. WeWork is a good example of the impact of architecture on culture and technology; it is revolutionary. Not just the spaces and program but also their use of an intelligent environment that is the platform for the use of machine learning as to how the spaces are used. Most architects aren’t paying any attention, but it is definitely working and a small group of architects are very involved.

MI

Is WeWork revolutionary as a form of practice, or as the spatial manifestation of that form of practice?

GL

Yes, both.

JS

Architecture has tended to support these practices rather than to drive them. It’s more at the level of furnishings that we’re starting to see the breakdown of conventional ideas about what a work space is. When it comes to location-aware furniture, or models of the workplace where the electrical sources are everywhere and not tucked in corners or tied to poles, we’ve barely begun.

When I think about architectural models for a future workplace that would leverage the power of these technologies, my mind gravitates toward theater design—in other words, toward mutable models of construction that are distant from what we typically think of as a “workplace.”

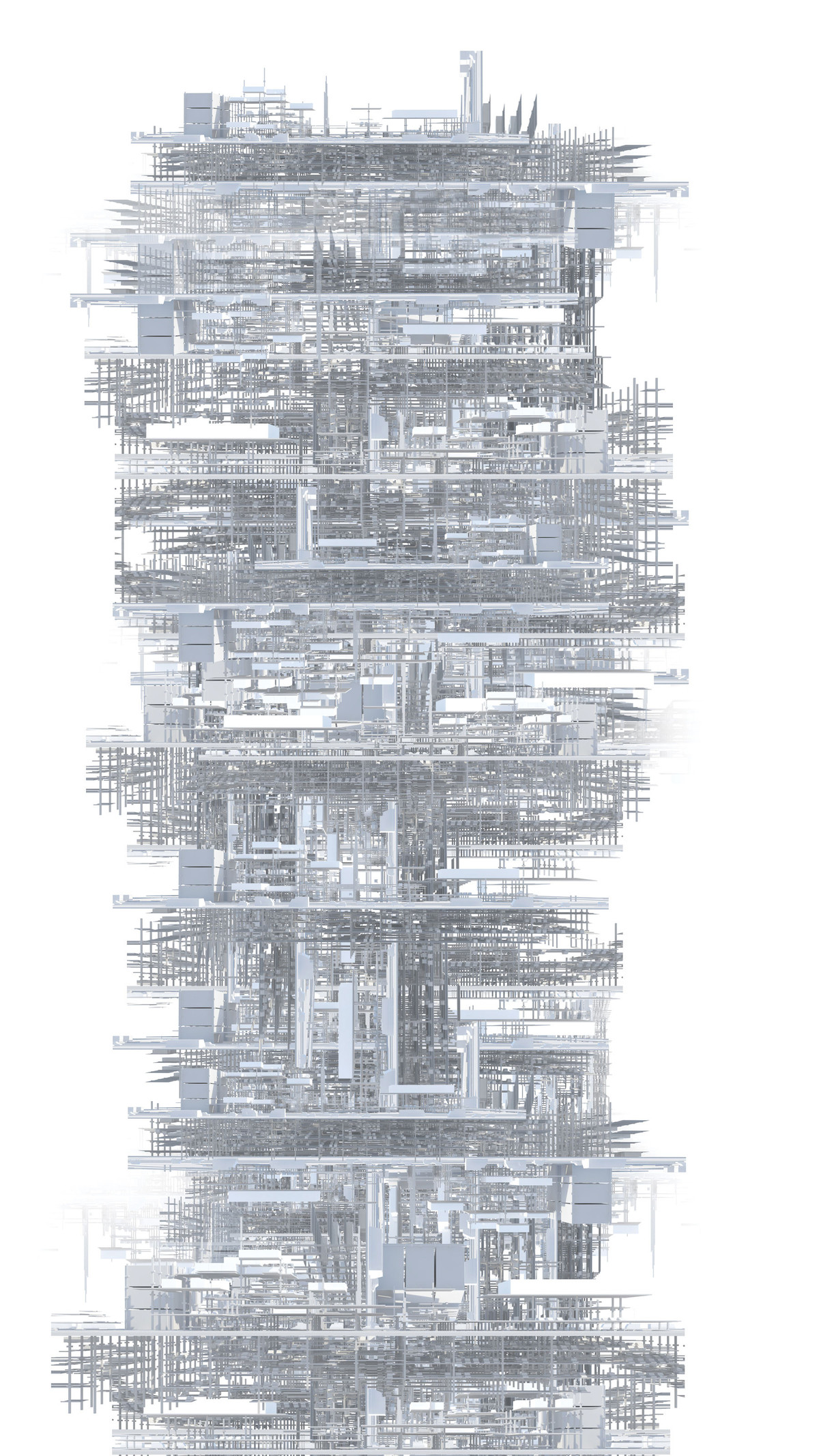

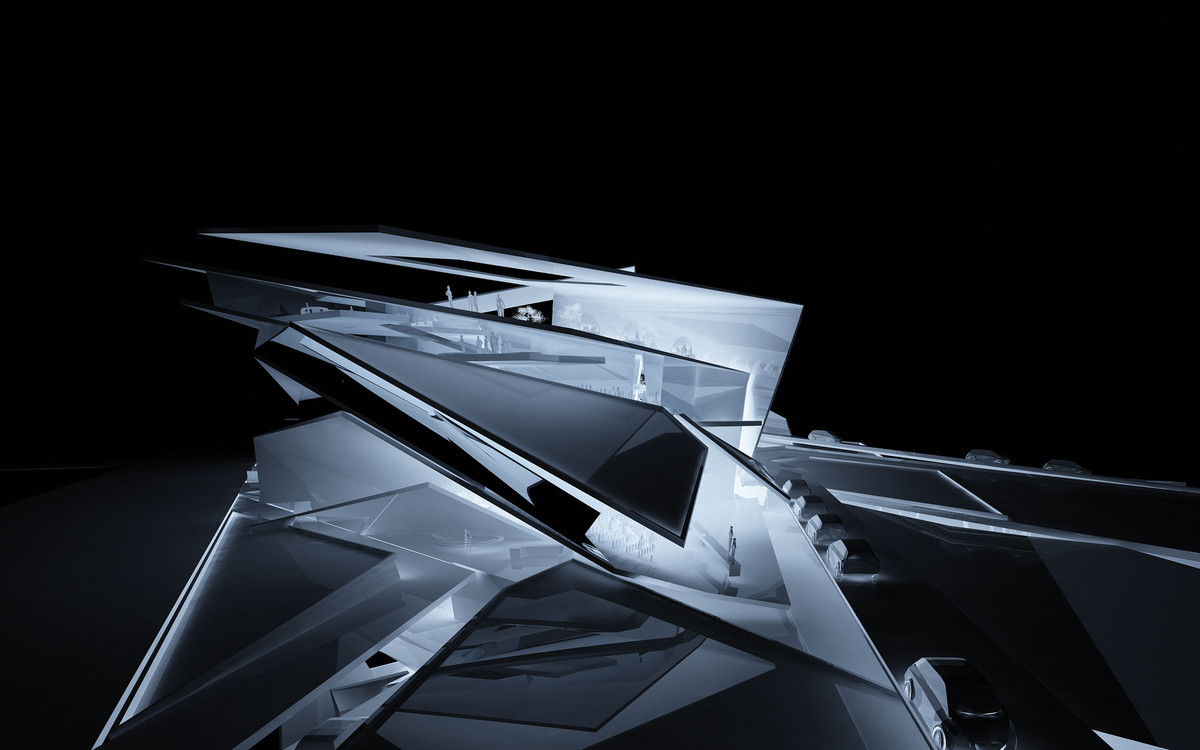

Some of the student projects were moving in that direction: for example, involving modular construction systems that allow entire units within a building to be shuffled in and out of the structure; automobiles that become extensions of office spaces; adaptive systems for facades, entries, and exits . . .

GL

The studio provoked a new kind of spatial and experiential response: people and robots need to be together, so we’re going to need something almost like a roadway of mobility in the building. Because we asked if robots need to be in their own space, the students came up with crazy ductworks, ceiling and floor plenums, and special entries and exits all for the robots.

MI

Architecture has historically been a slow profession: it takes a long time to design and build a building. What are the challenges that architects face when designing with the speed at which technological innovation occurs, and how are we negotiating those temporalities? Are we always reactive and problem solving? Or can we be generative, proactive, and visionary?

GL

The practice has gotten further and further downstream, because of risk aversion and specialization. Usually a site has been selected, a program has been defined, a budget has been established, a loan has been approved, and then the architect is brought in. Or, even worse, a competition is run to select the architect. That’s a really tough spot to be in, because, as an architect, your role is limited to delivering a service at the very end of a chain of practical and strategic decisions.

MI

So, you prefer to reimagine practice itself, not only what practice produces?

GL

There’s a pressure and an expected pace you have to keep when building for these companies—even considering the work of Norman Foster for Apple and Frank Gehry for Facebook. We need a different pace. Facebook demands a new building every 18 months.

MI

New technologies can render old technologies obsolete, but they also create new markets, new opportunities, and the need for new expertise. In that context, what are the technologies that architects should embrace?

GL

The ability to look at things over time and in motion, and their patterns of motion, is becoming more and more of a requirement.

JS

An extension of this need to track time and motion is understanding buildings as databases: that is, understanding a building as not just a series of volumes or masses, rooms and programs, but rather as a living, pulsing thing that produces information as it changes over time. The more that buildings become “smart,” the more they produce torrents of information. But that data is either relegated to a channel from which architects or designers are excluded or simply disappears into building and systems maintenance logs. That’s unfortunate because the data in question provides an opportunity for experimentation, reprogramming, and fine tuning. That’s where the WeWork spaces are interesting—they seek to leverage the power of that information and redesign the space continuously, treating the space less as a product than as a process.

GL

From an artistic and cultural point of view, it’s important that everyone thinks in machine vision and understands what it is, in the same way that Le Corbusier was looking at photography and cinema. When you see how a gita sees, at knee level, you start to imagine new opportunities. It’s important artistically to understand that the building and the machines in the building have a vision and a spatiality that’s not just about placing them, but also about how space is designed for machines.

MI

Computation has produced a vast number of tools and techniques for designing and making. In Log’s winter 2016 issue, ROBOLOG, which, Greg, you guest edited, and in the 2009 exhibition at the Canadian Centre for Architecture Speed Limits, you discuss some of the ideas that emerge from those practices and what they might lead to in the future. In the context of architecture, Greg, can you talk about big robots, and Jeff, about fast robots?

GL

I wanted to look at literal motion and how a building is a giant robot. I was amazed at how many architects were looking at the same problem without anybody acknowledging it—people like Liz Diller and Ric Scofidio and Rem Koolhaas were thinking of buildings as giant robots, but there was no discourse around it. I thought that was very interesting.

Today, there’s a lot of focus on things that are in buildings rather than the building itself as a robot. There was a great moment where we were picking carpet for our old space and were comparing two samples. They asked me, “Which one do you want, Greg?” I said, “I don’t know, show them to the robot. See if the robot can tell any difference.” The cameras localized 10 times better on one gray carpet over the other, although to me they looked exactly the same. So, I said, “Let’s just go with the carpet the robots like.”

JS

Robotically aided design selection! It’s always interesting to leverage the power of an augmented eye—whether that of a robot, a bee, or a fly: one that can go out and examine things that no human eye could ever see, either because of quantity, scale, or perceptual limitations. Estranging views tend to give rise to interesting outcomes. In my view, AI isn’t so much about replacing humans as it is a form of intelligence that can extend our capabilities or apply pressure

to our conventional perceptions.

MI

Some bright minds of the tech world continue to warn us about the dangers of AI. There seems to be a lot of cultural pessimism in the context of technologically affirmative environments. Are you pessimists

or optimists?

JS

We wouldn’t be here if we were pessimists. The markets will eventually decide whether we’re right or wrong, but we’re optimistic because we think these technologies, tools, and potential devices are transformative—certainly in as much as they allow people to do things that they can’t do today, but also they enable people who have mobility challenges to potentially move around the world with far greater ease.

GL

Within the field of architecture, we’re optimistic. There’s never been a better time to think about space and movement, and the possibilities of using technology in a different way. We don’t want to just adapt new technologies to buildings as we have been designing them, we want to design and build around these new technologies that will make their use and experience more human, more social, and more productive.

JS

Pertinent to this question is PFF’s motto, “Autonomy for Humans.” We’ve taken the word “autonomy,” ever-increasingly associated with the displacement of the human role in that defining form of modern mobility that is the driving of automobiles, and restored it to humans. Humans are already autonomous, you might (quite correctly) object; and the highest expression of that autonomy is walking. Walking is essential to health, the quality of life, and all aspects of our social well-being. Our aim at PFF is to build vehicles that support, sustain, and extend this fundamental aspect of biped identity. In the process, our goal is to support those who struggle with mobility, like the aging and the disabled.

We are optimists in that sense, but you have to make choices. Those choices are grounded in the larger vision of the kinds of cities we want to live in, the kinds of planning decisions we want people to make, and the kind of experimentation and creative work we want to happen in workplaces.

GL

And we’re megalomaniacal, like any architect would be. We want a normal person of modest means to be able to walk around with one of our robots and have it make their lifestyle better, like an architect would think they could make somebody’s life better by building their environment.

JS

The only robotic device that has achieved this level of success is the Roomba, a robotic vacuum cleaner. That’s hardly proof that robots have invaded everyday life! So you might say that we’re trying to devise vehicles that take a further step, a step out of the living room into the streets; vehicles that allow us to move more freely between interior and exterior places, between work and play.

MI

For people interested in technology and architecture, there are two questions that frequently get abused. One is quoting Cedric Price: “Technology is the answer, but what was the question?” And

the second is revisiting Charles and Ray Eames’s Design Q & A from 1972: “Can the computer substitute for the Designer?” Just to see where we stand, I want to ask you a few of those questions: “Can the computer substitute for the Designer?”

GL

No.

JS

No.

MI

“What are the boundaries of Design?”

GL

You wouldn’t situate the task of design in a building if you’re an industrial designer, and you wouldn’t situate it in gita if you’re an architect. But all of that stuff has to be designed. Less and less of the world is designed—there’s more mass design, for sure. When you look at everybody walking around with the same white things hanging out of their ears, the same gadgets in their hands, you realize that there’s a lower volume of design. Only a few things are being designed and mass produced.

MI

“What is the future of Design?”

JS

From where I sit, I tend to think about design as a translational practice. Translation is an apt and agile metaphor because it suggests that in order for design to take place there have to be other things at the table—depth of research, understanding the complexity of the problems that you are tackling, and the challenges and the opportunities presupposed.

MI

Actually, I think you just radically updated the Eameses’ answer to that question.

JS

Oh, I did? Good.

Greg Lynn is professor at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and the University of California, Los Angeles. He was a visiting professor at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design for the 2017–2018 academic year. He is the founder of Greg Lynn FORM, which, in addition to buildings, has designed consumer products for Vitra, Alessi, Nike, and Swarovski. He is CEO of the Boston-based company Piaggio Fast Forward, which he cofounded with Jeffrey Schnapp. Winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Architecture Award, he is the author of nine books.

Jeffrey Schnapp is the Carl A. Pescosolido Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and of Comparative Literature at Harvard University and is a Harvard University Graduate School of Design faculty affiliate. He is faculty director of metaLAB (at) Harvard, and faculty codirector of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. His work bridges the domains of cultural history, design, technology, and curatorial practice. In 2015, with Greg Lynn, he cofounded Piaggio Fast Forward, a Boston-based company devoted to building robotic vehicles that move the way that people move. He currently serves as Chief Visionary Officer of Piaggio Fast Forward.

Mariana Ibañez joined the faculty at the MIT School of Architecture and Planning after teaching at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design from 2006 to 2017. As an architect and academic, Ibañez’s research in architecture and its growing periphery has been focused on the relationship between technology, culture, and the environment. In 2007, she cofounded Ibañez Kim, a design practice that works with sensate materials, atmospheres, and new media to generate architecture, objects, and cities. She is the editor of three books and her work has been exhibited at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, MAXXI in Rome, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.