Fortress London: The New US Embassy and the Rise of Counter-Terror Urbanism

A squat glass cube rises above the banks of the River Thames in Nine Elms, southwest London, colored with the same dark greenish-gray pallor as the murky waters of the river itself. It has a similar medicinal hue to the cheap glazing of the speculative apartment blocks nearby, but this is one of the most expensive façades in town—and there’s a reason for its sludgy tinge. This building’s glass walls are six inches thick, formed from an elaborate sandwich of laminated sheets that make it capable of withstanding the most fearsome bomb a terrorist could throw at it.

The building might sound like the latest paranoid fantasy of London’s growing class of oligarchs and sheikhs. A class for whom high-security silos of luxury apartments are rapidly sprouting along this stretch of the river, in what is becoming a place of $45 million penthouses equipped with personal panic rooms. But this 11-story cube, which currently stands in the middle of a postapocalyptic scene of mud and cranes, is in fact the makings of the new $1-billion embassy of the United States of America. Its thick glass shell is merely one layer of defense in a sprawling five-acre complex that takes the architecture and urbanism of fear to new heights.

Housed in Eero Saarinen’s elegant Grosvenor Square embassy building since 1960, the US Mission to the United Kingdom decided to relocate when its ever-growing perimeter of bulky security paraphernalia could no longer be contained within the Georgian streets of Mayfair—and the terror threat could no longer be tolerated by its curtain-twitching neighbors. One local resident, a Russian countess named Anca Vidaeff, staged a hunger strike, while the neighborhood association took out two-page advertisements in the Washington Post and the Times of London to protest against the embassy’s presence. Regardless, a $15 million security upgrade in 2007 saw the building surrounded with a plethora of raised concrete flower beds, six-foot-high blast walls, guard shacks, and traffic-blocking structures, transforming genteel Grosvenor Square into a militarized scene worthy of Baghdad. But these additions were still not deemed enough to protect this outpost of Fortress America.

Following a series of high-profile attacks on US embassies elsewhere in the world—including lethal bombings in 1983 outside the Beirut mission, and then in 1998 at embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, during which 220 embassy workers were killed and thousands more injured—US Congress ruled that all embassies must be set back from the street behind a 100-foot “seclusion zone,” and be built within a self-contained site of at least four and a half acres. With the sale of Saarinen’s building to the property development arm of the Qatari royal family (which has hired David Chipperfield Architects to convert it into a luxury hotel), funds were used to acquire a former rail-yard site south of the river, close to Battersea Power Station. It was the equivalent of moving from Park Avenue to New Jersey, but it gave US authorities carte blanche to create a new piece of city planned entirely around their security needs, of a scale and level of control that London has never seen.

Walking past the hoarding that rings the construction site today, little would you imagine the world of defensive measures that are being conjured behind the innocuous plywood fence. When the Philadelphia-based firm KieranTimberlake unveiled its competition-winning design for the new embassy in 2010, the architects proudly declared that there would be “no fences and no walls.” It was an attempt to signal a departure from the introverted compounds being built elsewhere. The US embassy in Baghdad had just been completed in the form of a city-sized complex of concrete bunkers set behind layers of imposing walls, while the Bush administration’s Standard Embassy Design program seemed intent on populating the world with a grim family of prefab sheds.

In contrast, “openness and transparency” were KieranTimberlake’s watchwords. The design, the firm explained, was inspired by European castles—not in having 20-foot-thick stone walls and chutes for showering boiling oil down on the enemy, but in that the building’s defensive strategy would be hidden in the landscape. In principle, the scheme isn’t too far from a medieval motte and bailey. The 200-foot glass cube is raised up on a hill, set back from the nearest street by over 100 feet, and surrounded by a moat—or a “pond,” as the architects would prefer you to call it.

Within this defensive buffer zone, the planning application drawings reveal a fascinating world of military-bucolic strategies, a tactical topography of “hostile vehicle mitigation” techniques woven into an undulating idyll of prairie grasses and weeping willows.

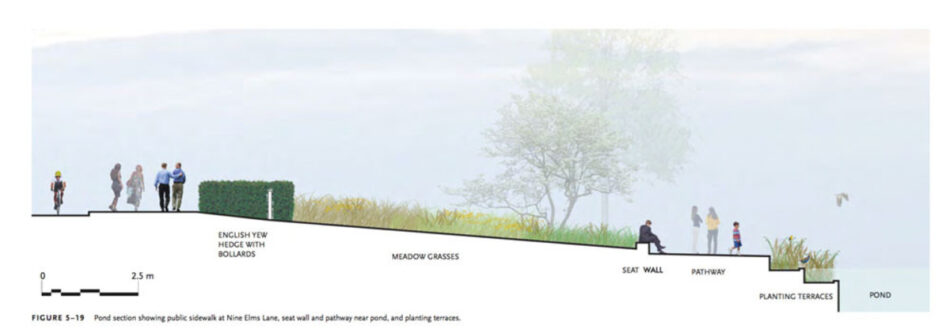

To the north, the site is bordered with an English yew hedge, which leads to meadowland planted with species native to North America (“analogous to the special relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom,” the architects reason). But this isn’t any old yew hedge. Secreted inside the foliage will be a line of steel and concrete bollards capable of stopping an eight-ton truck driving head-on at 40 miles per hour. If, by some miracle, a hostile vehicle does break through the hedge of steel, it will be confronted by a wall of seating at the other end of the meadow, along with two sharp changes of level, and then the great pond—a 100-foot expanse of water, behind which the embassy stands on a raised plinth, its defensive wall disguised by a gushing waterfall.

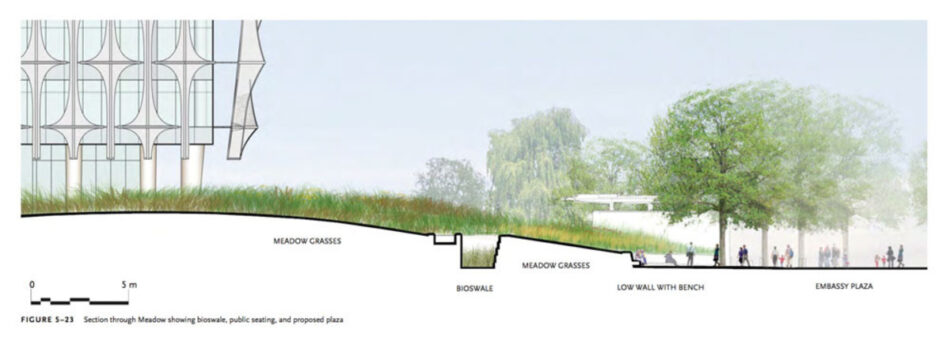

To the south, the site is edged with another seating wall—benches affixed to a thick slab of truck-impeding concrete—behind which the landscape rises in a defensive berm, a.k.a. a “meadow” with the “sense of expansion characteristic of the rolling American plains.”1 As the cross section in the planning application shows, a third of the way along this mound the ground plummets into a steep ditch. It is labeled as a “bioswale” for environmental purposes, but it just so happens to be conveniently scaled so as to trap any kind of moving vehicle that might try to make a break across the meadow. It is a traditional British ha-ha, originally used to keep animals off the lawns of country houses, updated for 21st-century security needs.

With the embassy soon to be surrounded by a complex of 2,000 luxury apartments in the form of the Embassy Gardens development—where every building will be set back at least 150 feet from the embassy’s building line—this new high-security enclave is just the latest example of how terrorism has become one of the key forces shaping the nature of London’s urban fabric as the city moves toward becoming a network of gated islands.

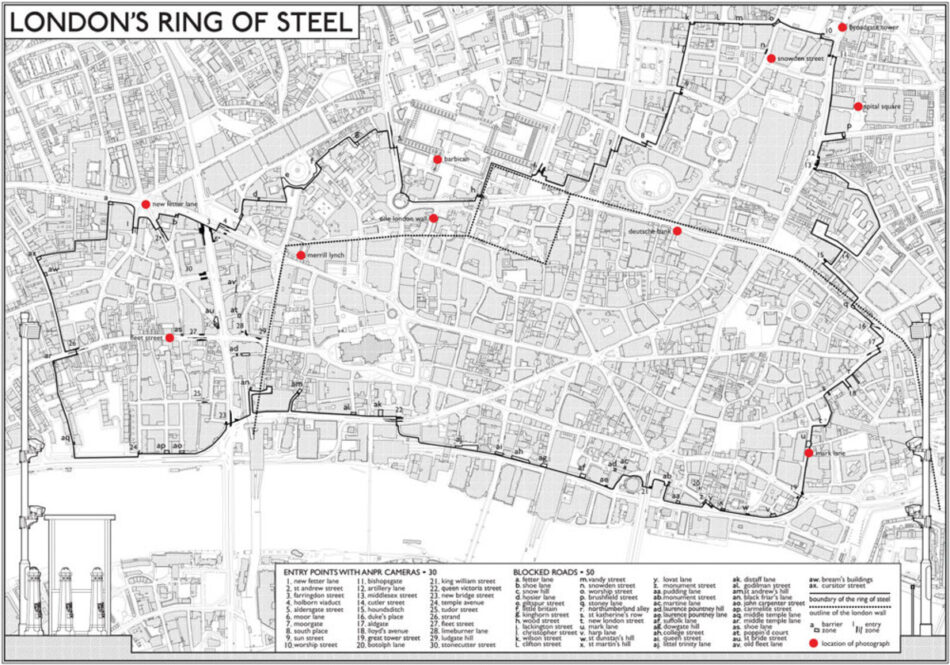

The City of London first introduced a necklace of perimeter security measures—known as the Ring of Steel—in the early 1990s, in response to the terror threat posed by the IRA after a 1993 bomb attack wreaked havoc on Bishopsgate. Beginning as a very visible line of plastic bollards and police checkpoints, it has gradually dissolved into a barely perceptible border of CCTV cameras and license plate recognition software, rising bollards and strategic planting, chicanes and road closures, with the effect of progressively reducing the number of access points in and out of the Square Mile, making it easier to shut the city down at a moment’s notice. In many ways it has returned the financial capital to the medieval walled city of yore, the hefty wall of stone and mortar simply replaced with barriers of a more surreptitious kind.

It is a subtlety that the Palace of Westminster, home to the House of Commons and Lords, has yet to catch on to. While the government departments of neighboring Whitehall recently lined their streets with ornate Portland stone balustrades, which are cleverly reinforced inside with steel crash-proof bollards, Parliament itself is still surrounded by a blockade of gargantuan black steel barriers, as if civil war had recently broken out.

Parliament’s MPs might do well to visit London’s annual Security & Counter Terror Expo, a sprawling trade fair of paranoia, which proudly claims to showcase “the key terror threat areas under one roof,” and how they can be tackled with ever more sophisticated products.2 Among the stands peddling surveillance drones, bomb-disposal robots, and portable forensics labs are endless varieties of bollards and fencing, available with any number of different “toppings”—from electrified wires and sensor detection systems, to good old lacerating razor wire. One of the biggest sections of the show is made up of hostile vehicle mitigation devices disguised as street furniture, showing how several tons of concrete and steel can be variously hidden inside benches, planters, and other hefty lumps to further clutter the sidewalk. Visit any of the capital’s major sights today—from the pseudo-public spaces beneath the Shard and Walkie-Talkie skyscrapers, to Kings Cross Station and the Olympic site—and you’ll see clusters of these seats-on-steroids, the contemporary city’s equivalent of moats and ramparts, only cloaked in a costume of granite and foliage.

The perimeter security industry has boomed in the United Kingdom since 2007, when terrorists succeeded in driving a truck loaded with propane canisters straight through the glass doors of Glasgow Airport, setting the terminal ablaze. Two unexploded car bombs were discovered in London the same week. A few months later, the government issued extraordinary guidance to architects, planners, and developers, specifying that new buildings should be set back from the road by 164 feet, windows should be no larger than 32 square feet, and masonry cladding should be avoided on any building taller than two stories. At the same time, the National Counter Terrorism Security Office began running seminars in schools of architecture, advising students on designing with terror in mind, from retaining open sight lines in public spaces to what kind of cladding materials perform best in the event of a bomb blast.

“We know that right now our public places are under surveillance from individuals who are trained to look for vulnerability,” intoned the narrator on the accompanying training video. “The truth is some structures and spaces can actually assist in their appalling ambition. Maybe you can’t see the responsibility you have got. Until you do we are back to where we started, back to anxiety, back to fear.”3

But such a position fails to recognize that any sense of fear is in fact spawned by these very doctrines of defensive design, of counterterror regulations dreamed up in the immediate wake of an attack, which have created a new kind of anxious urbanism. It is a world of public spaces hemmed in by bollards spaced so close they feel walled off, of streets where you can’t move because of oversized planters, of a city planned with a sense of imminent catastrophe. If fortress urbanism now trumps our ability to make spaces conducive to civic life, then the terrorists have already won.

http://www.architectural-review.com/archive/london-uk-an-interview-with-kieran-timberlake/8600486.fu…. 2 “Counter Terror Expo 2015 to Cover Key Terror Threat Areas under One Roof,” Government and Public Sector Journal, February 2, 2015, http://www.gpsj.co.uk/?p=3126. 3 Quoted in Robert Booth, “Home Office Urges Architects to Design Terror-Proof Buildings,” Guardian, March 21, 2008, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2008/mar/22/terrorism.uksecurity.

Oliver Wainwright is the architecture and design critic for the Guardian. Trained as an architect at the University of Cambridge and the Royal College of Art, London, he has worked for a number of practices, including OMA and muf, as well as in strategic urban planning for the mayor of London’s Architecture and Urbanism Unit. He has written extensively on architecture and design, and is a visiting critic and lecturer at architecture schools internationally.