Mammoth and Other Frozen Meats

Meat rots. This simple biological fact has dictated how, when, and where humans procure fresh protein for as long as we have been hunting. But the advent of cold storage changed our meat consumption—and trade—profoundly. Once localized to a radius dictated by perishability, by the late 19th century meat traveled from New Zealand to London, feeding the upwardly mobile whose diets adapted accordingly. Because of its organic properties, meat’s nascent global economy came with some uncertainties—the most disconcerting of which was food poisoning suffered most often by those who could afford the novelty of imported steaks. Eating meat from cold storage soon attached itself to an era of culinary one-upmanship by gentlemen who anchored experiments in meat eating to their masculinity by tempting safety, challenging technology, and pushing the boundaries of shelf life.

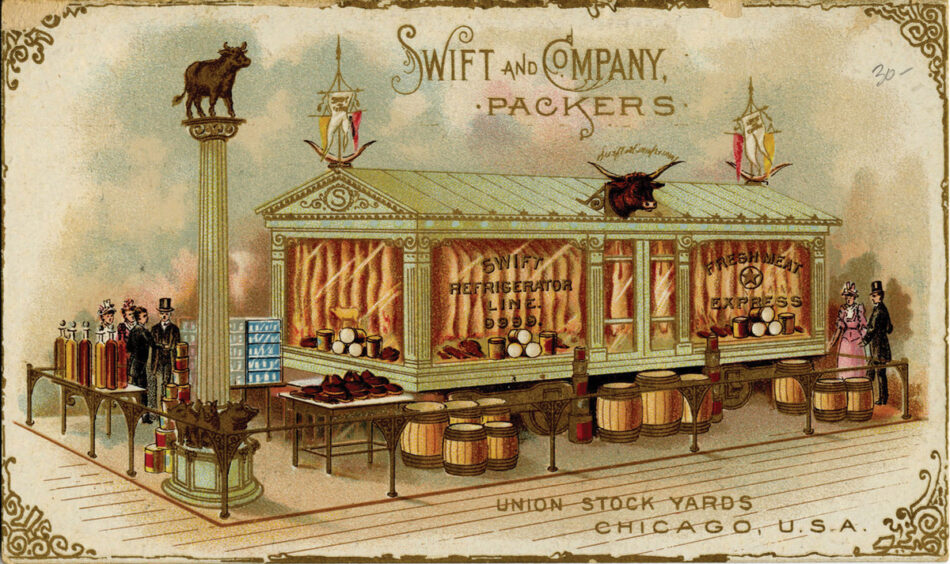

Much of the American public did not understand the finer, more molecular points of germ theory, but they certainly had enough sense to know that improperly preserved meat posed a serious threat to their health. By the turn of the century, meat packers in Chicago—the heart of the industry—were sending slaughtered goods across the country to consumers in refrigerated rail cars, and the public contemplated the fact that they could, and increasingly did, eat animals that had died some time ago. Safety concerns permeated national consciousness from events like the “embalmed beef scandal” of 1898 that rocked American troops with dysentery during the Spanish-American War. Rather than source fresh beef from local herds, as per military tradition, low-quality rations came—frozen and canned—by train, and then ship, from the midwestern hub. In particular, the frozen beef “had an odor similar to that of a dead human body after being injected with preservatives,” reported Chief Surgeon of US Volunteers William H. Daly. Events like this showed that (aesthetically speaking) frozen meat could look just fine, even if it had already gone putrid.

It is in this environment of frozen meat and masculinity that one finds a particular history of dining spectacles aimed at testing the limit of how long meat could be stored on ice and still remain edible. Enterprising groups took knife and fork to actively aging meat, curious to know what it might taste like.

A Freeze

In the 1860s, just as engineers began to grasp the mechanics of refrigeration, Texas cattle ranchers saw business opportunities open up in not-too-distant New Orleans, a spectacularly wealthy

port city separated from them and their livestock by the yawning Gulf of Mexico. Scrambling to capture the market, two steamships out tted with huge cold storage rooms—Thaddeus Lowe’s William Tabor and Henry Peyton Howard’s Agnes—raced their frozen cargos across the Gulf. History doesn’t remember Lowe, whose vessel took on too much water when docking in New Orleans, but it does remember Howard, in no small part because of the fanfare devoted to Agnes’s arrival. Inspectors meeting the ship reported that the beef butchered the previous week arrived “in perfectly good order, and looks today as though it were freshly slaughtered.” A banquet held in celebration at the St. Charles Hotel, a noted bastion of excess, provided the perfect place for the public to sample Howard’s triumph.

A Longer Freeze

By the 1880s, cities across the United States had refrigerated distribution hubs for food products—like beef—that might have been raised in Texas, dressed in Illinois, and served in New York City. Emboldened by the newfound harmlessness of three-week-old steak, upper-class diners were left to wonder what the temporal and gustatory boundaries might be for frozen meats. Prominent New York stockbroker Edward Bell tested these limits in 1891 when he served dinner party guests a Vermont turkey that had been hanging in the Knapp & Van Nostrand cold locker for a full 10 years before being thawed, drawn, and prepared. Guests reported that the bird looked remarkably good for its age, but tasted terrible. “[They] ate the turkey with emotions of lively surprise and interest,” one article reported, “but were not long in discovering that it had entirely lost its avor. The flesh was . . . dry as a bone. All the essential juices had disappeared.” After chewing for some time—on what we can imagine as, basically, shoe leather—the diners agreed that if one hoped to enjoy the taste of previously frozen meat, it would be prudent to store it for a maximum of one year—even if aesthetics and safety could be preserved for “a practically indefinite period.”

The Longest Freeze

An infamous Explorers Club dinner held at New York City’s Roosevelt Hotel in 1951 put the conclusion made at Bell’s feast to a fantastic test, when, according to the Christian Science Monitor, attendees dined on “250,000-year-old mammoth meat.”* The gathering of the world’s most traveled and adventuresome men (no women allowed) sampled morsels for which they thanked Father Bernard Hubbard, who claimed to have acquired the mammoth after its emergence from the permafrost of Akutan Island in the Bering Sea. The decor mirrored the dish: grasses and shrubs were flown in from Kodiak to simulate the tundra. While the Monitor did not report on the mammoth’s taste, it did note that it pleased the diners more than the main course of bison, which was “a bit tough.” If one could dream up a dinner of gross hypermasculinity, they would be challenged to do better than this night, with a Paleolithic beast served as the hors d’oeuvre.

Not two years would pass before Swanson’s TV dinners appeared in the freezers of American homes. By then frozen meat no longer held novelty for the average American diner—and holds little still. Storing food in cold temperatures has, in fact, become the de facto technological development upon which the global food system operates today. Recalling these past experiments with taste and time are useful signposts, however, to remind us how quickly frozen foods became wrested from the world of uncertainty to be domesticated by marketing and mothers—now bastions of comfort, safety, and modern convenience.

*Or was it the Megatherium, an extinct ground sloth? There were competing recollections of the legendary dinner up until 2016, when researchers at Yale University performed DNA testing on a sample of the dish, which had been preserved by a curator of Connecticut’s Bruce Museum, Paul Griswold Howes, a member of the club who couldn’t make it to the event. The jig is now up. The meat actually came from a green sea turtle and was served (probably in jest) by the event’s organizer, Wendell Phillips Dodge.

Hiʻilei Julia Hobart is a postdoctoral fellow in Native American and indigenous studies at Northwestern University. She researches the intersection of food, technology, and taste, and is currently preparing a book manuscript on the history of ice and the taste of coldness in Hawaii.