Shahidul Alam on the Majority World

A Bangladeshi photographer and activist who was named a Time magazine Person of the Year in 2018, Shahidul Alam has spent decades critiquing power through images, words, and the many institutions he has helped build. From documenting the effects of floods and cyclones to interrogating extrajudicial killings, he treats his subjects with a respect too often absent in the Global North’s media. Alam’s refusal to stay silent has consequences, though—most notably when he was tortured and imprisoned by his government in 2018. Yet even as his trial looms, this self-proclaimed fighter for justice has not put down his camera or ceased speaking out against corruption.

While attending an exhibition of his photographs in Belfast in 1989, Shahidul Alam was staying with Irish friends. Their five-year-old daughter, Corrina, took to him, and the two often would share stories. One night, Alam encountered a confused Corrina, as she watched him remove coins from his pockets. He asked her what was wrong. Her response surprised him: she had never seen a Bangladeshi with money. The image was incomprehensible to her.

Corrina’s observation spurred Alam toward the institution building that has accompanied his award-winning, four-decade career as a photojournalist and activist. “If a five-year-old grows up in an environment where she’s incapable of seeing a Bangladeshi as anything other than an icon of poverty, that needed to change,” Alam says from Dhaka, where he has lived his entire life except for a few years in the United Kingdom where he earned a PhD in chemistry. “I felt the way to do that would be to have different storytellers than the ones who always portrayed us.”

In keeping with an African expression of which he is fond—“Until the lions find their storytellers, stories about hunting will always glorify the hunter”—Alam and his partner, the anthropologist and writer Rahnuma Ahmed, set up Drik Picture Library in Dhaka in September 1989. As he describes in his latest book, The Tide Will Turn, the Sanskrit word “drik” means “vision, inner vision, and philosophy of vision,” which is embodied in the agency’s primary goal of creating “a more egalitarian world, where materially poor nations have a say in how they are represented.” To that end, Alam and his peers continuously challenge both the limitations and prejudices of the global media ecosystem as well as domestic conditions and politics. Opening the nation’s first gallery that took photography seriously, they began showing work deemed too controversial by those who ran both the local and foreign-operated exhibition spaces. They also sought to improve the quality of photography production in Bangladesh, paying for their equipment with door-to-door sales of small products such as postcards and calendars.

“One of the ways in which one can keep a state in check is through robust institutions that have intrinsic value,” Alam explains. “In my country, all the institutions have been demolished: the police have been turned into a private army; the judiciary is toothless; the education system has been dismantled. By creating a culture through establishing value systems that people can relate to, these institutions will have an impact when you and I have gone.”

Pathshala South Asian Institute of Photography, which grew out of Drik and is also based in Dhaka, emblematizes Alam’s concern for future generations. Since 1998, it has educated thousands of Bangladeshi photographers and cemented their high standing at international competitions and their subsequent inclusion in prominent publications. Alam was its first local teacher. In its first years, he was joined by international friends in the industry including Chris Boot, Reza Deghati, and Kirsten Claire. Robert Pledge, Daniel Meadows, Martin Parr, and many others donated their time too. Today, 24 of the 26 faculty members are Pathshala graduates.

These advances were in turn bolstered by Chobi Mela, the first major photography festival in Asia and now its most prestigious. Founded by Alam in 2000, the biennial event distinguishes itself as the “most demographically inclusive photo festival in the world” and provides opportunities for cultural and artistic exchange. There, Bangladeshis speak with and see work by internationally acclaimed photographers who, in turn, learn from those they may not otherwise meet. “A lot of editors, photographers, and writers have come and really woken up to the fact that there is such high-quality work being produced in a country like Bangladesh,” Alam says. “They have become, in a sense, our ambassadors when they’ve gone back [to the Global North].”

Some of Alam’s peers reject any engagement with hegemonic powers, whether their institutions or their representatives. He considers such outright dismissals naive. “I will not throw out the baby with the bathwater. It’s not just the subaltern that I’m trying to get at. I need to have an impact in the gallery circuit,” he says. “I recognize those spaces that have power and want to be at that table, because I’m aware that I can shout my voice hoarse from down below and it won’t matter. But at that table, I can speak in an articulate manner and perhaps have a bigger impact. Because these are elitist spaces is not a reason for me not to occupy them. By withdrawing from those spaces of contestation, you’ve given up the battle before it has begun. I’m in a battle, and I will fight to win.”

Alam, while humble, gracious, and soft-spoken in conversation, does not restrict himself to small gestures. Many of the problems he addresses exceed the borders of his home country. And rejecting the exhibition of his work in a strategic fashion remains part of the battle. Last year, the Prix Pictet touring exhibition Hope featured Alam’s focusing on his friend Hazera Beagum, a former sex worker who runs an orphanage where she cares for and educates the children of sex workers, drug addicts, and others, without taking any salary. The series, entitled Still She Smiles (2014), continues his long-held determination to represent marginalized people with grace and dignity, such as those with HIV/AIDS, the rural poor, Indigenous communities, factory workers, and Rohingya refugees. When the exhibition was due to open at Tel Aviv’s Eretz Israel Museum, he boycotted it. “To show [in an exhibition] called ‘Hope’ in a museum built on land from which Palestinians have been evicted simply cannot happen to my work. So I took it away,” he says. The South African photographer Gideon Mendel also removed his pieces.

Bangladesh, he has always known, is not unique in being roped into the demeaning “Third World” category by those in the so-called First World. “I didn’t want to be third of anything,” he says. “Certainly we have not chosen you to be the ‘First World’ and us to be the ‘Third.’” A different phrase was necessary. The one on which he settled—majority world—directly critiques the hypocritical rhetoric used by superpowers in the Global North, which praises democracy and freedom while its leaders support “pliant dictators” and assert their dominance over any region they desire. “North America constitutes about 5 percent of the world’s population; Europe is about twice that. Yet you speak on behalf of all of us who never chose you to do so and who happen to be the majority of humankind,” Alam says. “Based on the rhetoric of democracy, we should have a significant say in the way this planet operates—which, of course, is not the case.”

In 2004, “majority world” lent its name to another photography agency which Alam co-founded with British organizational consultant Colin Hastings. Based on the belief that local photographers can best understand and capture their own people and locality, both for themselves and others, Majority World began to represent photographers in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and elsewhere in Asia. Now the group also includes Native American and First Nations peoples.

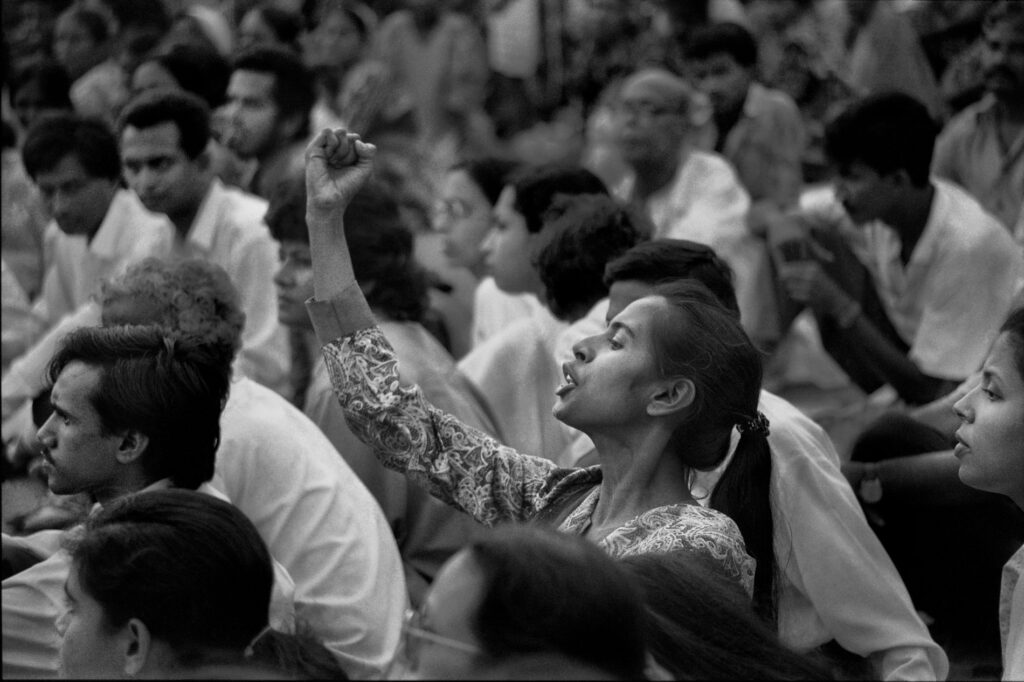

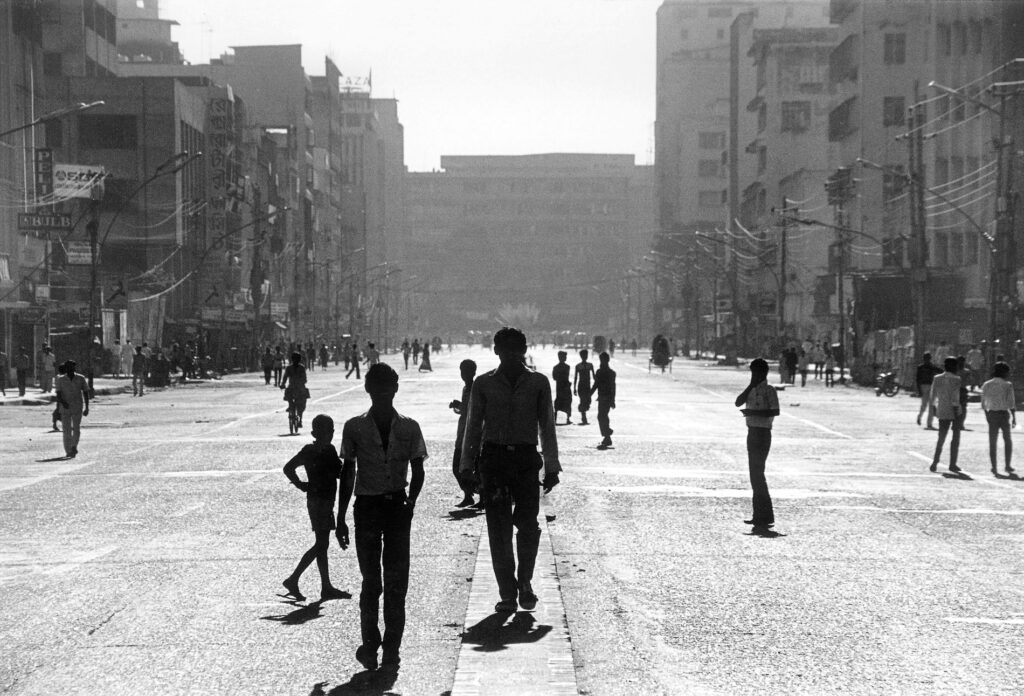

While Alam’s dedication to international initiatives remains paramount, he keeps his attention fixed on local corruption and injustice. As a result, exhibitions throughout his long career become major, and frequently contested, events. From December 12–15, 1990, at the Zainul Gallery, immediately after the fall of General Hussain Muhammad Ershad’s military dictatorship, Alam and his colleagues displayed photographs mounted on cardboard which documented the resistance movement. Approximately 400,000 people attended the impromptu show at a gallery that until then had refused to show work critical of the government.

In 2017, he sought permission to stage the exhibition Embracing the Other within Dhaka’s Bait Ur Rouf Mosque—a controversial choice because of the belief held by some Muslims that photography is haram. The show featured portraits of devotees as well as images of the mosque’s caretakers and its delicate architecture. When grouped together, they capture the essence of a cultural space built for and appreciated and used by an entire community. Alam argues this was the intent of the first mosque in Medina, where foreign dignitaries were welcomed by the Prophet, women were invited to sleep and non-Muslims to pray, medical care was administered, and even a theater troupe performed. In keeping with his goal to resuscitate an original understanding of these sacred spaces and to fight Islamophobia, he stipulated that all people, regardless of class, religion, or sex, be granted access to the exhibition. While members of the ruling political party at first pushed the show outside the mosque, women and children—unaware of the party’s objections—brought it just behind the qibla.

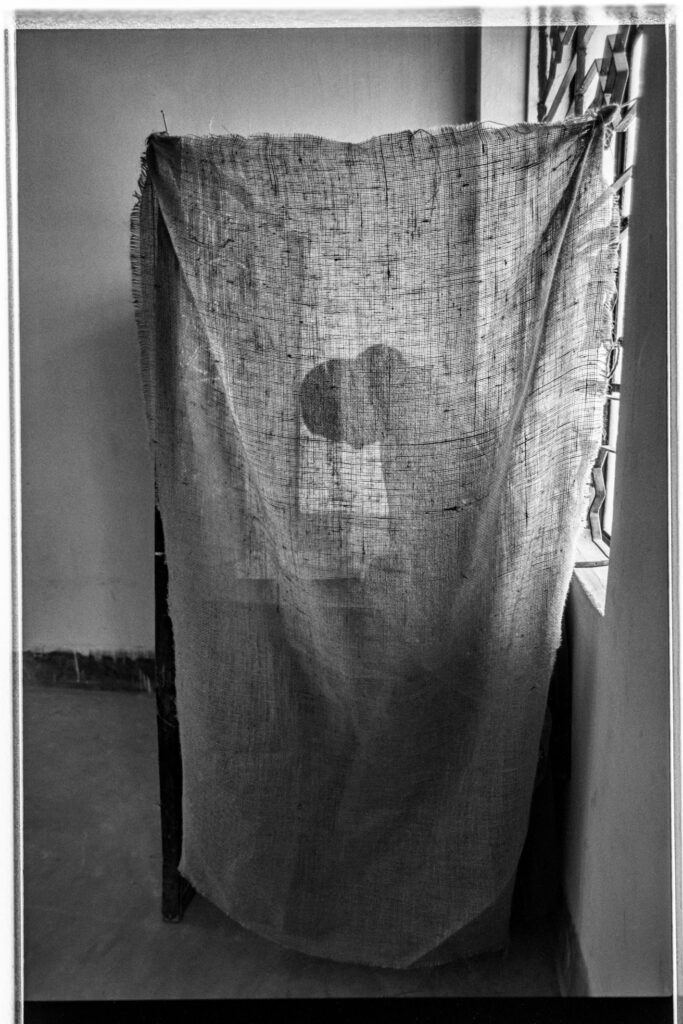

Even more controversial has been his work that addresses extrajudicial killings by Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion, which the government calls “crossfire.” Taking this euphemism as the name for the series, Alam explores how successfully photography can or cannot capture absences. To do so, he employs an innovative forensic approach to his subject: the photographs could be read as the final images witnessed by those killed. For example, the dominant photograph, “Paddy Field,” appears as a benign, even beatific, landscape. Its connection, however, to the word “crossfire” in the gallery subverts this reading. “To see the work, to appreciate it, you have to engage with the politics,” Alam says. Police closed the show before it opened.

After decades of challenging state power and subverting its rhetoric in public forums, Alam feared he might become one of his country’s disappeared. On August 5, 2018, he gave an interview to Al Jazeera about the anti-government corruption protests which followed the deaths of two students who were struck by a reckless bus driver. That evening, more than 20 officers stormed into Alam’s home and arrested him. He was subsequently tortured and imprisoned for 107 days.

A trial still awaits him, for charges related to Section 57 of the Information and Communications Technology Act—a statute which, in essence, allows the government to arrest anyone they claim has posted material online it deems “fake,” “obscene,” or “defamatory,” among other loose categories. If convicted, he could serve 14 years in jail.

Despite no longer being able to move freely in Dhaka due to safety concerns, Alam remains steadfast against leaving Bangladesh. “One wants one’s life to have meaning,” he explains. “My presence in the USA would make very little difference to the USA. My presence in my community matters to my community. I am able to shape a future around me. That’s an incredible feeling to have, that your life has meaning in some way and matters to the people around you. I go to sleep raring to wake up for what I want to do the next day.”

“I have a roof over my head. I don’t have to worry about whether there will be food on my table tomorrow. In a country like Bangladesh, that’s a very privileged life,” he continues. “This privilege has been given to me by the garment workers, the migrant workers, the farmers in the field who are the real heroes of my country. I owe it to these people. I’m just repaying a debt.”