Shifting Landscapes In-Between Times

“What Time is this Place?” asked Kevin Lynch, exploring how communities manage environmental change.1 His question was prescient. Globalization of technologies, societies, and economies is transforming the world along diverse and unforeseen pathways, and landscape architecture is challenged by the need to both respect the past and confront the certainty of an uncertain future.

1. Time and Landscape

Landscape architecture theorists and practitioners typically frame their understanding and response to landscape change as a dialogue with an evolving and emergent landscape2 that has accrued meaning and significance “like a patina.”3 Alexander Pope wrote of the environmental conversation which informs landscape design, consulting an enduring genius loci—the water, topography, and vegetation.4 More recently, Ian McHarg reframed the conversation as one of “design with nature,” arguing that landscape intervention be grounded in the contextual study of landscape processes.5 His mapping and layering approach is now widely used to systematically grasp the “the flowing face of nature in its motion”6 and to project future design relationships.7

However, in our conversations with landscape and in projecting design possibilities, landscape architecture must always anticipate the unknowable. The “stuff” of landscape—the materiality of soil, plants, water—is dynamic, transient, and to a significant degree, indeterminate. Much contemporary design has been reconfigured as a process that progressively transforms urban landscapes along multiple ecological dimensions.8 A related shift is a reorientation of design goals from program9 to performance.10 Design outcomes become expressed as a rich and diverse stream of services and values11 such as biodiversity, heritage or recreation, and their expression is inevitably less easy to define and predict than the form of particular object or surface installations. However, some assumptions about continuity in the material conditions of landscape are still needed. Examples of “open-ended” design are typically set in known landscape contexts—even if particular sites are in flux—and are based on predicted or assumed relationships within landscape. As McHarg expressed it, they still presume “the place (is) because,”12 and make assumptions about how it will “become.” Design “open-endedness” is thus conditional and bracketed within known landscape processes, institutional arrangements, design operations, and construction methods.

Landscape architecture also typically presupposes a relatively predictable temporal frame, which provides opportunity for careful analysis and leisurely conversations with the genius loci. Engagement with biophysical and cultural contexts grounds us in place, whether reading the landscape of Pope’s hills, vales, and waters, or interpreting the contemporary voids of urban decay. But how can design be imagined when the conversation with landscape is radically disrupted? What happens when design context, design object, and landscape relationships all become indeterminate?13

In this essay, we reflect upon experiences of a series of major earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand to explore conceptual, emotional, and material dimensions of uncertainty in landscape architectural theory and practice. The earthquakes and their aftermath provide vivid insight into the enigma of design in a truly dynamic landscape. Rather than a benign character progressively revealed and shaped as a pleasant setting for a postcolonial city, the genius loci of Christchurch has been dramatically unmasked as a force possessed, prone to violent and unpredictable outbursts.

Perhaps the problem is that, as designers, we misunderstand the significance of indeterminacy. The contemporary world is in thrall to the paradigm of choice and open-ended possibilities—What would you like to buy? Which scene do you prefer? Which design should we select and how many different ways might it turn out? Sudden, unpredictable, and traumatic landscape transformations challenge the presumption of ever-expanding choice and the excitement of uncertainty, and instead focus attention upon how to make decisions over those things that are vital to life and which we can have some hope of influencing.

The earthquakes began in September 2010 with a 7.1 magnitude event on a known fault some distance from the city. Hopes of return to normality were shattered on February 22, 2011, when two shallow and locally intense quakes on a previously unknown fault close to the Central Business District (CBD) caused widespread devastation, resulting in 185 fatalities. Over 10,000 aftershocks have since shaken the region, and continued as we wrote some 18 months later. Such seismic events radically recast temporal frames and demand profound rethinking of our place within landscape. They highlight the vastness of geological time, the instantaneous nature of change, and amplify its recurring unpredictability. Other contemporary landscape dynamics are also unpredictable—economic crises, civil unrest, and climate change and its effects—and such conditions are arguably becoming more “normal” than the relative stability experienced in much of the developed world since 1945. Our reflections in the face of intense tectonic change are therefore offered here as insights into understanding and designing the “new normal” of shifting landscapes “in-between times,” of working in those temporal conditions where everything is suspended in an indeterminate state. These ‘in-between times’ heighten the very nature of landscape as process, while landscape as product—‘finished’ plazas, streetscapes, parks, and gardens—is revealed as an illusory aspiration, a hoped for future in the face of constant, relentless change.

2. Ruin Time and Landscapes Past

While geological time provides a conceptual measure for physical landscape, the vastness of time becomes palpable through the presence of relics and ruins. Often compared to natural landscapes, particularly when weathered and invaded by vegetation, ruins are central to landscape architecture’s engagement with the past.14 However, while established ruins confer continuity and are familiar cues for place identity in conventional design responses, new ruins are distressing and unsettling, a raw wound in our consciousness. Whether from earthquakes or human-induced disasters, new ruins are confrontational, and the experience—especially where lives were lost—is intensely emotional.

Aesthetic appreciation of recent ruins is also ethically fraught, from John Ruskin’s critique of the “heartless picturesque”15 to Damien Hirst’s controversial statement that the ruins of the World Trade Center were a “visually stunning artwork.”16 Recent ruins are emphatically sublime, terrific, and incomprehensible, but only time can provide the lens to appreciate their beauty. As literary critic Jean Starobinski observed, for a ruin to be beautiful, “the act of destruction must be remote enough for its precise circumstances to have been forgotten” and then “it can then be imputed to an anonymous power, to a featureless transcendent force–History, Destiny.”17 Florence Hetzler calls this “ruin time,” a temporal interlude in which a damaged structure loses its raw and painful appearance.18 Rose Macaulay describes this shift when she writes how bombed cities, like ancient ruins, needed “the long patience and endurance of time” before they “mellowed into ruin.”19

Design involving recent ruins is thus conceptually, emotionally, and politically unsettling. In Christchurch, the controlled deconstruction of the central icon of the city, Christchurch Cathedral, has generated intense debate and confrontation. Can or should the damaged structure be stabilized and restored, or is the process too dangerous? How could this be afforded, when there are pressing social needs for housing? What is the design response to calls for a memorial garden in the footprint of the contested building? These decisions require a consideration of different physical, emotional, economic, and political risks—a dimension of practice as yet underdeveloped in our discipline.

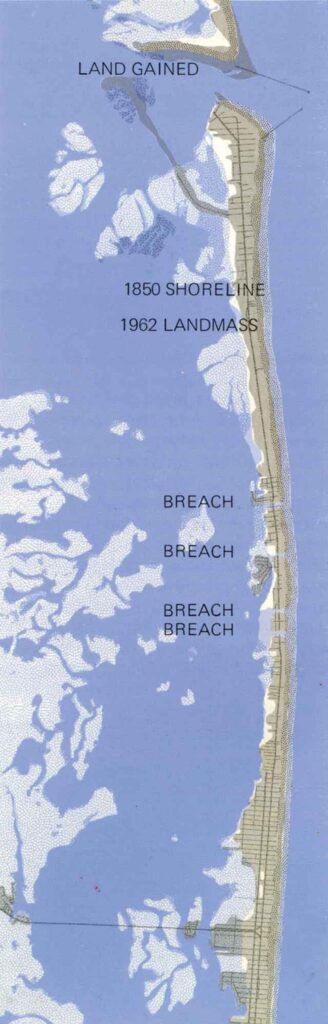

The new and raw landscape ruins of the wider city are equally challenging. Significant parts of the eastern suburbs of Christchurch are uninhabitable. Many were built on former wetlands now revealed to be unsuitable due to lateral spread and soil liquefaction, and are “red zoned” (in the new local language of planning)—meaning their residents must resettle elsewhere. It is not that the genius loci was mute on such natural hazards when the suburbs were created—rather, those responsible were selectively deaf in their conversations, and did not “read the signs.”20 The ruptured landscape now lies partly abandoned while government deliberates on its future. The designated red zone is a truly landscape-scale ruin, as opposed to the object-like ruins of buildings. And herein lies one of the critical problems of large-scale sudden and unforeseen change—the landscape and its communities need time to respond and evolve, to adapt to a new state and set of conditions.

While interventions at the scale of an object or even a site can be relatively quickly made, at the landscape scale the complexity of the biophysical landscape, as well as the entwined and complex nature of the cultural landscape, including such challenges as property boundaries, means that change must be incremental. Landscape planners and communities can quickly generate exciting possible futures, such as proposals for the naturalization of damaged areas as future flood protection parks,21 but the agencies responsible have to reconcile many conflicting imperatives, intensified through crisis. Faced with the socio-economic aftermath of violent change, there is an overriding desire to clean up, repair basic infrastructure, and restore both public and private cash flows. At the same time, this is precisely when imagination and vision are most needed to initiate strategic changes in the way we live,22 and enable society to better adapt to the revealed dynamics of landscape. How can these conflicting imperatives be reconciled? One option is to seek out pressure points where modest actions can have community-wide significance, for example by foregrounding evidence of the events as a prompt for collective action.

3. The Unexpected and the Surreal

Strange juxtapositions in the landscape heighten our appreciation of time. Through drawing attention to the extraordinary within the ordinary, surreal landscape moments intensify our apprehension of places. Sometimes the landscape’s strangeness can emerge from incremental changes over time, where erosion creates ghoulish forms, or vegetation grows in seemingly impossible places. At other times, the landscape becomes surreal with shocking suddenness. Abrupt and unexpected changes in the landscape can result in strange new configurations as earthquakes or tsunamis transform seemingly immutable landscape elements. This creates opportunities to strategically curate change,23 to mark and re-present the process and experience of landscape transformation—recording the past while shaping a new future.

Preservation of tangible evidence of change—ruins, landscape fragments—is difficult in immediate post-disaster regimes, but can be profound in its effect. After the 1995 earthquake in Kobe, Japan, severely damaged land in the port area was left unrepaired, and is now “exhibited” in contrast to the landscape context. In 2011 in Ishinomaki, Japan, a memorial offered itself from the wreckage. A giant can, previously used as an advertisement, was washed onto the street by the tsunami. Recognizing its potency as an objet trouvé—a ready-made—the can was left in the middle of the road and traffic diverted around it. Its emergence from the devastation, a product of the dramatic force of the event, resonates with the Ground Zero cross, which materialized from the ruins of the World Trade Center after 9/11. Kobe’s damaged land, Ishinomaki’s big can, and Ground Zero’s steel cross all endured the post-disaster period to become curated landscape fragments that bear witness to past events.

Unexpected objects and sites thus present potent possibilities in the curation of the landscape. Akin to curating exhibits in a gallery, these elements can be revealed and amplified, while the landscape around them proceeds to a new condition. These small features of the landscape offer a kind of datum against which landscape change can be referenced, representative evidence— a cross, a giant can—that becomes a microcosm of wider events, a landscape synecdoche. The products of an instantaneous shift that produced unexpected results, these landscape elements embody notions of attachment and meaning in the wake of disaster. In Christchurch, such fragments are yet to be curated in any systematic way, but the possibilities lie ready—boulders still strewn along side roads, collapsed cliffs abutting abandoned houses, heritage buildings lying shattered behind security fences—and there is also opportunity to curate change more explicitly in the way future parks are reconfigured out of land abandoned as a “red zone.”

4. The Recurrent: Transient Landscapes and In-Between Times

Recurrent but unpredictable natural events create distinctive and profoundly unsettling temporal regimes. Landscape theorists and practitioners are familiar and accomplished at designing around and through predictable cyclic phenomena such as diurnal changes in light, temperature and activity, seasonal changes, lifecycles, ecological successions and so on. Even irregular events like rainstorms are framed statistically, with predicted return periods providing a conceptual design platform for storm water systems. Prediction of earthquakes, however, remains a dark art. Furthermore, earthquakes bring aftershocks, some as devastating— or in Christchurch, more devastating—than the original event, but impossible to predict. The continuing shaking has created a Sisyphean sense of recurrence, as attempts to restart life are set back or undone—and the sustained unpredictability of in-between times makes landscape reconstruction problematic.

At the time of writing, the Christchurch earthquakes are the world’s third most financially expensive natural disaster. Topped only by the 2011 floods in Thailand and the 2011 Japanese tsunami, costs were disproportional to the physical magnitude of the event because of extensive insurance. However, insurers now argue over liability for each new event and are reluctant to provide further coverage while aftershocks continue.24 Significant parts of the CBD remain closed as high rise buildings are deconstructed,25 and many suburban areas still await insurance decisions on future occupancy.

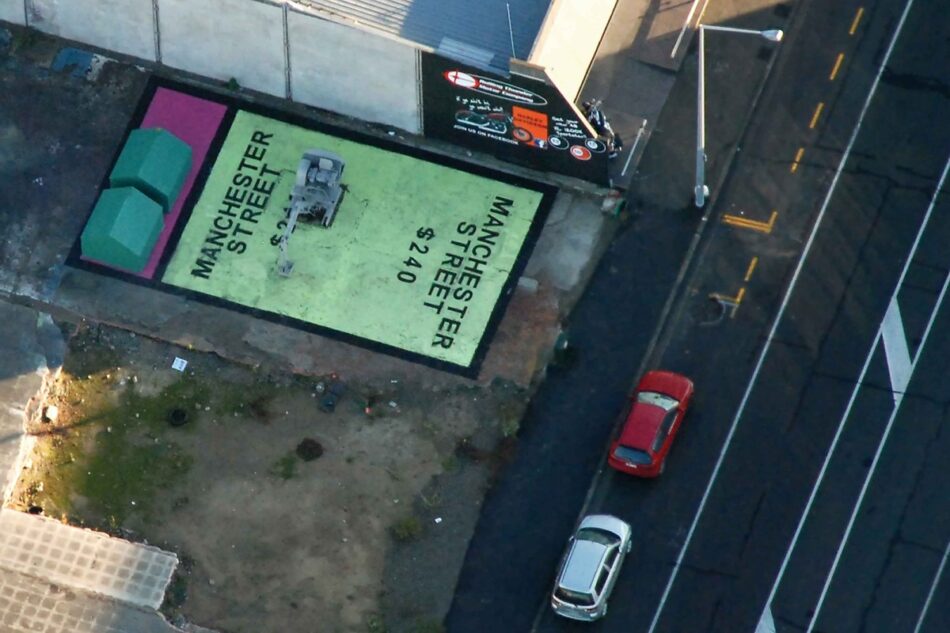

In such in-between times, innovative approaches to landscape intervention provide alternative means of reactivating the city. These are intentionally transient, moving from site to site to accommodate the constantly morphing nature of the city. Community organizations such as Gap Filler and Greening the Rubble claim vacant sites for temporary landscapes. A Dance-O-Mat (a moving platform powered by an old Laundromat washing machine with an iPhone dock to provide music) a giant chess set, and outdoor bowling alley have been created. The city as a landscape at the mercy of some exterior force is suggestive of a board game, where the roll of a dice determines which buildings stay, or are demolished, and which color different parts of the city are zoned. Playing on this, one intervention takes the form of a colored square, complete with two houses, and a digger as the game token, all suggestive of a well-known property acquisition game. Projects like these are reminders of the importance of humor as a coping strategy, where small and simple designs can bring delight and relief amidst the bleakness of a wrecked city. Close by, a shopping precinct of shipping containers is a hub of activity amidst soon-to-be demolished buildings and razed sites in the CBD. When relocated to other areas as rebuilding commences, the temporary shops become catalytic, colonizing and reactivating the expired city, and fostering the slow change that characterizes landscape-scaled responses.

Memorials also take temporary form. Working against the grain of embedded associations of memorials with permanence—with the vastness of time—there is an escalation in temporary memorials worldwide in response to tragedy.26 Memento-strewn fences marked sites like the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and in Christchurch, the security fences excluding the community from the CBD also became sites for the expression of the loss of both people and buildings. On the first anniversary of the February quake, artist Henry Sunderland’s symbolic and poignant landscape vision of encouraged residents to put flowers in thousands of road cones became a city-wide memorial. Temporary memorials imbue even the most humble landscape objects—fences and road cones—with heightened significance, reminders that the power of landscape comes not from big budgets and expensive materials but through creativity and thoughtfulness.

5. The Challenge of Strategic Action in Uncertainty

One theoretical response to uncertainty has been to reshape landscape intervention as contingent, drawing upon the concepts of emergence, open-endedness, and indeterminacy which were first foregrounded in the Parc de la Villette competition, and have continued to characterize theoretically informed landscape design. The core idea of contingency was articulated by Rem Koolhaas in relation to OMA’s Villette entry: “The program will undergo constant change and adjustment. … The underlying principle of programmatic indeterminacy as a basis of the formal concept allows any shift, modification, replacement, or substitutions to occur without damaging the initial hypothesis.”27 However whilst intellectually appealing and aesthetically rewarding when framed within a familiar context, a programmatic strategy of non-decisions creates major challenges at both personal and collective levels when it becomes a dominant condition. As Robert Somol argued about the Downsview competition, “[t]oo often in its dominant form of process-obsession, contingency indicates an abdication of a professional role rather than a desired end-state condition that one must proactively work to install.”28

However, identity, meanings of home, work and leisure, and even professional roles are all undermined by continuing uncertainty. In central Christchurch, over 1,000 buildings—some 50% of the CBD—will be demolished, including many of the city’s most significant heritage structures: a painful index of the shifting character of the urban landscape. In the suburbs, over 7,000 houses so far have been condemned, and many thousands more await repair. Newspapers report daily on families, businesses, and communities struggling to rebuild their lives. Often taken-for-granted, the loss of both everyday landscapes and special heritage features dislocates the basic functions of life and undermines sense of place, creating a kind of vacuum, as the very fabric of the city’s identity is cordoned off or gone completely. Like a phantom limb, there is a continuing sensation—the feelings are still there—yet the physicality and function is absent. Throughout the city topophilia has morphed into topophobia, where much-loved landscape features of rivers, hills, rocky cliffs, rivers, and heritage buildings all became sites of fear due to risk of soil liquefaction, rock fall, and collapse, and the remains of familiar workplaces, cafes, and meeting places are bulldozed away.

What landscape architectural strategies are possible in such extreme conditions of indeterminacy? Michael Hough’s sage advice to minimize interference in communities and do “as little as possible”29 is inadequate when whole landscapes are transformed, and there is pressing human need for homes and a healing of community, but contemporary design strategies based upon extensive mappings and speculative reconfiguration of urban infrastructure are equally tangential. The most constructive landscape actions to date have been localized bottom-up initiatives, as different communities take control of their futures, despite rather than enabled by government. This is most evident in neighborhoods with legacy social capital. Peterborough Village Pita Kaik, a neighborhood on the margins of the CBD, is developing its own reconstruction plans,30 inspired by resident landscape planner Di Lucas. A network of designers in the coastal suburb of Sumner has developed plans for revitalization.31 The port town of Lyttelton is establishing a food cooperative, and a bar constructed from containers and a petanque court on a cleared site now provide community focus.32 A larger scale initiative is focused upon the city’s Avon River, where ground damage due to liquefaction was most evident and where the majority of the suburban “red zone” is concentrated, and the Avon-Otakaro Network (AvON) is lobbying government to create a city to sea park system across abandoned land.33

Inevitably, many community based initiatives tend to be framed in conventional terms—a “wished-for world”34 based on familiar ideals from the past. What is most challenging under such dislocated conditions is to envisage new strategic possibilities that can deliver long term “necessities of landscape performance.”35 Brett Milligan’s concept of “corporate ecologies”36 envisages strategic action being implemented through organisational networks, rather than by top-down policy or single site intervention. In Christchurch, it is not corporations, but non-governmental organizations and not-for-profits such as Gap Filler, Greening the Rubble, and the Student Volunteer Army that have emerged as key agents in bottom-up recovery actions.37 They prefigure a significant extension of landscape architectural activity from specific sites, to multiple spaces and places of engagement with landscapes—where human relationships with landscape are “designed” through manipulating the tools and practices of everyday life.38

6. Design Strategies for Shifting Landscapes In-Between Times

Is it possible to design for unpredictable change? Some types of episodic change are already recognized as factors which will transform landscapes in ways that can be foreseen, but at unpredictable times. Sea-level rise and storm surges, drought and flood, and yes, even earthquakes can be anticipated to occur at some future time. Human-created events such as financial booms and crashes are also to some extent anticipated as inevitable, albeit unpredictable. Perhaps the earthquake sequence in Christchurch can therefore offer some insights upon design in shifting landscapes in-between times that are more relevant to our discipline.

The first is that in conditions of uncertainty it is vital to pay careful attention to what is known. If Christchurch had collectively and politically acted upon the knowledge of landscape dynamics already embedded in its institutions, then many lives would not have been lost, and communities and families would not have been living and working in vulnerable places. We have also learnt that the time of crisis is too late to connect landscape knowledge with the wider community. One consequence of the Christchurch earthquakes has been a review of earthquake preparedness across New Zealand, and this is extending to a re-evaluation of the way all natural hazards are handled in planning. As Anne Whiston Spirn has argued,39 the language of landscape needs to be continually relearnt.

Second, one of the most profound experiences in Christchurch has been recognition of the continuing power of the local. Neighborhoods with inherited social capital or that had invested in community building were better able to respond and have led in planning for reconstruction. In a globalized and uncertain world, community based action becomes ever more important as a way to strengthen local relationships and capacity to adapt to the challenge of in-between times.

Third, at a city-wide level, the dependence of public services upon a single CBD and unitary infrastructure systems has been shown to be vulnerable, and the earthquakes have accelerated a transformation of the city region towards a more distributed urban form. It has been striking how quickly the economic activity of the wider city region rebounded, despite a vacuum in the center, and there are lessons for the shape and nature of resilient urban form. The privately owned suburban shopping malls and commercial centers have quickly become the new urban centers by default. However they lack public facilities and there is a clear imperative for public authorities to engage more closely with the privately owned supermarkets, malls, and business parks to ensure they have the range and quality of public services they need for the new roles they fill as civic centers in a redistributed city.

The Christchurch experience also suggests that during in-between times, when the landscape is undergoing profound and constant change, there is need to focus on targeted design action that will have tangible and beneficial outcomes—on what can be achieved, rather than what might be desirable in better and more certain times. Such actions may be small in scale, but if replicated through city wide networks, can grow to have strategic consequences. Viewed from our shifting landscape, the potential of contemporary theories of urbanism lie not so much in the creation of open-ended, city-wide design projections, but rather in the power and possibility of locally based but strategically conceived landscape and community regeneration. When faced with pressing material and community needs, landscape indeterminacy cannot become a design rationale for indecision. Instead it must provoke a search for practical actions of modest individual scales but cumulative strategic significance.

Finally, it is clear that aspirational visions retain their potency, despite uncertainty. As this article goes to press, the reconstruction authority has released a ‘blueprint’ for a rebuilt city center. Based upon an earlier community visioning process (Share-an-Idea), the plan is focused upon restarting economic activity within a more compact, ‘green’ CBD. Landscape as product re-emerges to attract investment in the midst of ruin, reminding us of the ever-changing complexity of landscape dynamics in-between times.

Emily Waugh has provided most helpful commentary and editorial advice. However, the main acknowledgement must go to the many Christchurch people who are contributing hope, time, and energy to heal their shattered city landscapes.