Ship Shape

The title of Maggie Nelson’s 2015 memoir The Argonauts comes from a Roland Barthes essay about a crew that rebuilds the body of its ship over the course of a voyage at sea: “A frequent image: that of the ship Argo (luminous and white), each piece of which the Argonauts gradually replaced, so that they ended with an entirely new ship, without having to alter either its name or its form.” At the beginning of the story Nelson tells her lover that she associates the ship with the phrase “I love you”—the phrase’s meaning changes with each utterance, not to mention the “I” and the “you” and the “love”—and the book goes on to recount many related instances of transformation. Indeed, embodiment, subjectivity, and love here are all characterized by a sense of renewal, voyage, and journey that might be likened to the mythological ship’s passage.

Bodies, in particular, are constantly in flux: Nelson experiences pregnancy and birth for the first time, and her partner, the artist Harry Dodge, begins injecting testosterone and eventually opts for top surgery. If “consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” as Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, for Nelson it is the hobgoblin of little-minded bodies. Here, inconsistency, and the responsibility that comes with it, becomes a virtue.

For Nelson such an idea is tied not only to the desire to rethink questions of gender, sex, and the body in the 21st century, but also to reconsider the very notion of family. She wants to imagine a definition of the term that would accommodate queer and procreation and care altogether. She is remarkably sensitive to the implications of her project, both its pleasures and pains, as evidenced by her evocative ruminations on stepparenting. “No matter how much love you have to give, no matter how mature or wise or successful or smart or responsible you are, you are structurally vulnerable to being hated,” she writes. Clearly, such a retrofitting will not be easy and yet the new ways of coming together that she maps out are crucial, suggesting the emergence of an ethics of radical openness.

What would it look like to extend Nelson’s claims to the realm of spatial production? For Nelson, family still finds its place in the single-family home. Set in Los Angeles, The Argonauts plays itself out in a horizontal field where bodies achieve equal parts distance, intimacy, and solitude in rapidly gentrifying foothill neighborhoods. Refuge is taken in the shadow of “our mountain,” but space as a concept receives less definition, suggesting, perhaps, that “construction” today is more focused on bodies and communities than sites. Though there are moments when such questions body forth— the book’s opening scene, for example, recounts “the first time you fuck me in the ass, my face smashed against the cement floor of your dank and charming bachelor pad,” drawing a strong connection between spatial dynamics and the intensity of sexual experience—correlations between space and subjectivity are generally left open to the architectural imagination.

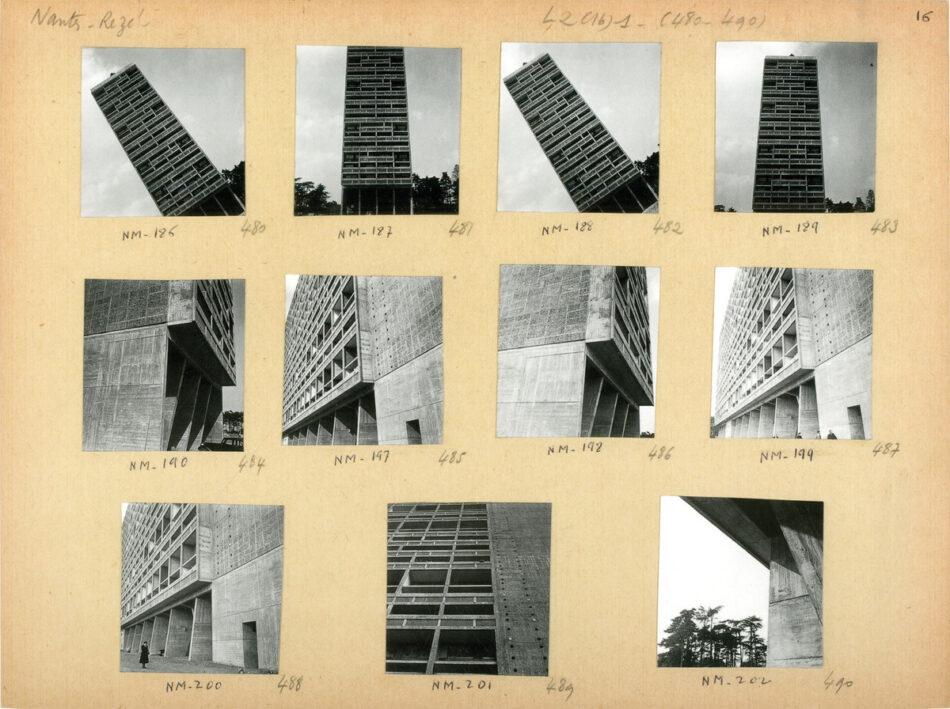

It is difficult for me to think about the Argo and its metaphors without remembering the illustrations of the great transatlantic liners—the Flandre, the Aquitania, the Lamoriciére—that Le Corbusier used to illustrate Vers une architecture. For Le Corbusier, these great ships served as models for contemporary architecture: their massive scale and industrial quality challenged some of the discipline’s most cherished ideals, and signaled the advent of a new spirit. While the influence of such thinking can be seen on an aesthetic level in Corb’s contemporaneous projects—the white horizontal swath of the Villa Savoye, for instance—the idea of the ship as a space that houses a great number of people would more profoundly influence the design of his major postwar projects, especially the Unités built in Berlin, Briey, Firminy, Marseille, and Rezé, which consolidated new collective bodies in a world undergoing reconstruction.

Over the years the shortcomings of these projects have been duly pointed out—their remarkable lack of storage space is only one example—but their intense focus on community remains a defining feature. What would it look like, then, to think the Argo alongside, say, the Flandre? Might this not be a way to think infrastructure and intimacy, repetition and difference, together? Might the nuclear family give way to something more like a network? Indeed, in this scenario the ship would be bigger than any one body—it would necessarily be a body politic, as Nelson herself suggests.

If we are to reconstruct ourselves, it seems, we must remake our spaces as well. And over time we might join our ships together in a fleet.

Alex Kitnick is the Brant Foundation Fellow in Contemporary Arts at Bard College. His writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Artforum and October.