Tales of an Absent Monument

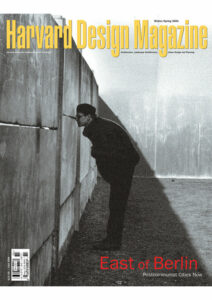

What is most remarkable about the Zizkov Monument (c. 1925–33) is its inconspicuousness. It’s not that the building can’t be seen. Rising from one of the tallest hills in the city, the quarter-mile-long mass of gray granite marks the horizon from almost every vantage point in Prague, and the 16.5-ton bronze figure of warrior Jan Zizka astride his battle horse—reputedly the largest equestrian statue in Europe—juts out from the skyline at all sorts of unexpected places as well. Nor is it that the monument “repels attention,” in keeping with Robert Musil’s thesis about the inherent invisibility of public memorial structures1; its importance as a setting for political ritual during the communist era guarantees its indelibility in the Czech collective memory for at least another generation. It seems rather that, despite its massive physical and symbolic prominence, the Zizkov Monument suffers from a condition of all-absorbing emptiness, as if it were a black hole within contemporary Czech society.

Views of the Monument to National Liberation in Prague

For much of the last decade—since the 1989 “Velvet Revolution” that ended four decades of communist rule—the monument has been practically voided from Prague’s cultural map. The building has been closed to the public except during special events since 1993, and until recently prospective visitors had to apply to the Ministry of Culture for access. Now the site has been transferred into the care of the National Museum, which hopes to reopen the doors permanently in 2002; even among those planning its revival, however, supporters of the monument are few. And yet the Zizkov Monument offers a grand opportunity to showcase key aspects of modern Czech culture that have decidedly international resonances. To grasp this building in its entirety—its architecture and design, its complicated cultural and political history—is to begin to understand the indissociability of modernism from the state, of progressive democracy from authoritarian rule, and ultimately of presence from absence. The Zizkov Monument is built on a strong foundation of paradoxes, and the exceptional clarity with which it manifests these paradoxes, in both its form and its history, merits attention.

Even in a country long accustomed to the ideologically motivated appropriation of buildings and statues, the Monument to National Liberation and Memorial to Jan Zizka of Trocnov on Vítkov Hill (to give its full name) presents a case of exceptional mutability. The building and the ideas that inspired its construction have variously served the needs of nationalists, liberals, fascists, communists, and even a venture capitalist. The original concept dates to the 1870s, when Bohemian patriots called for a statue on Vítkov Hill to commemorate the Hussite warrrior Jan Zizka, who won a strategic victory there in 1420 against a largely non-Czech crusading force. Stories of Zizka’s patriotic fervor and military prowess galvanized separatist sentiment during the last decades of Habsburg imperial rule—witness the 1869 decision to rename the entire neighborhood “Zizkov”—and a public competition for his statue in 1913 elicited over five dozen submissions. Nothing came of this initial effort, but the inspiration Czech soldiers and citizens derived from Hussitism during the First World War helped turn Zizka into a mascot for an expanded monument project in the 1920s. Veterans and leaders of the newly autonomous Czechoslovak nation (one of several countries created by the postwar breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) now supervised the project, announcing competitions in 1923 and 1925 for a structure to house state meetings and anniversary ceremonies, and above all the remains of legionnaires who had died fighting for an independent Czechoslovakia. From a beacon of nationalist promise, the Zizkov Monument was to become a symbol of promise achieved.

In 1925, the architect Jan Zázvorka won the competition to design the monument, only to spend the next thirteen years watching his proposal take shape. Plans for the site, by far the largest public works project undertaken in the Czech lands, called for a three-story edifice with a commemoration hall and presidential meeting room on the main floor, a mausoleum complex and memorial to fallen legionnaires at ground level, and a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to be located under the statue of Zizka in front. As the country neared the twentieth anniversary of independence in October 1938, the building seemed ready at last for a grand opening, although it still lacked the crowning symbols of an Unknown Soldier and the statue of Zizka himself. But that same month, the Western European powers fatefully agreed in Munich to cede part of Czechoslovakia to Hitler’s Germany. With the country’s statehood effectively at an end, dedicating a monument to national liberation seemed tragically pointless.

The Wehrmacht occupied the site immediately upon entering Prague in 1939, and one year later a general decree calling for the destruction of all objects symbolizing Czechoslovak autonomy placed the building’s many decorative works in danger. Thanks to a daring campaign by ex-legionnaires and other patriots, most portable items were spirited into hiding, while several mosaics and massive marble reliefs were ingeniously plastered over to blend into the surrounding walls. For the historian attuned to irony, these undeniably courageous acts had an inadvertent symbolism; they foretold the building’s progressive erasure in the postwar decades. Its current invisibility seems unwittingly foreshadowed in this campaign to protect the identity of the place by emptying it of its contents or blanking it out.

If the war years were a singularly unpropitious time for Czech nationalists and national monuments, the postwar era would prove nearly as challenging. But for a brief period in the 1950s, the Zizkov Monument came into its own. Following the Communist Party coup of February 1948, Klement Gottwald, known as the “first workers’ president,” chose the building as a showcase for the new socialist state. To the casual observer, the place continues to look the part. It has the impersonal massiveness and forbidding loftiness Czechs associate with that era of show trials and labor camps, and the idealizing verism and gargantuan scale of the Zizka statue fit perfectly with the glorification of Hussitism propagandized in communist-era history texts. The statue is in fact one of several important parts of the monument (another is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier) designed in the 1920s but put in place only after 1948. Further additions, most notably the Red Army Hall, were planned and built entirely during the first years of communist rule. Although these later additions are often inferior to the designs of the interwar period, they do extend its grandiose premises, and conceptual continuity was assured by the participation of the original architect.

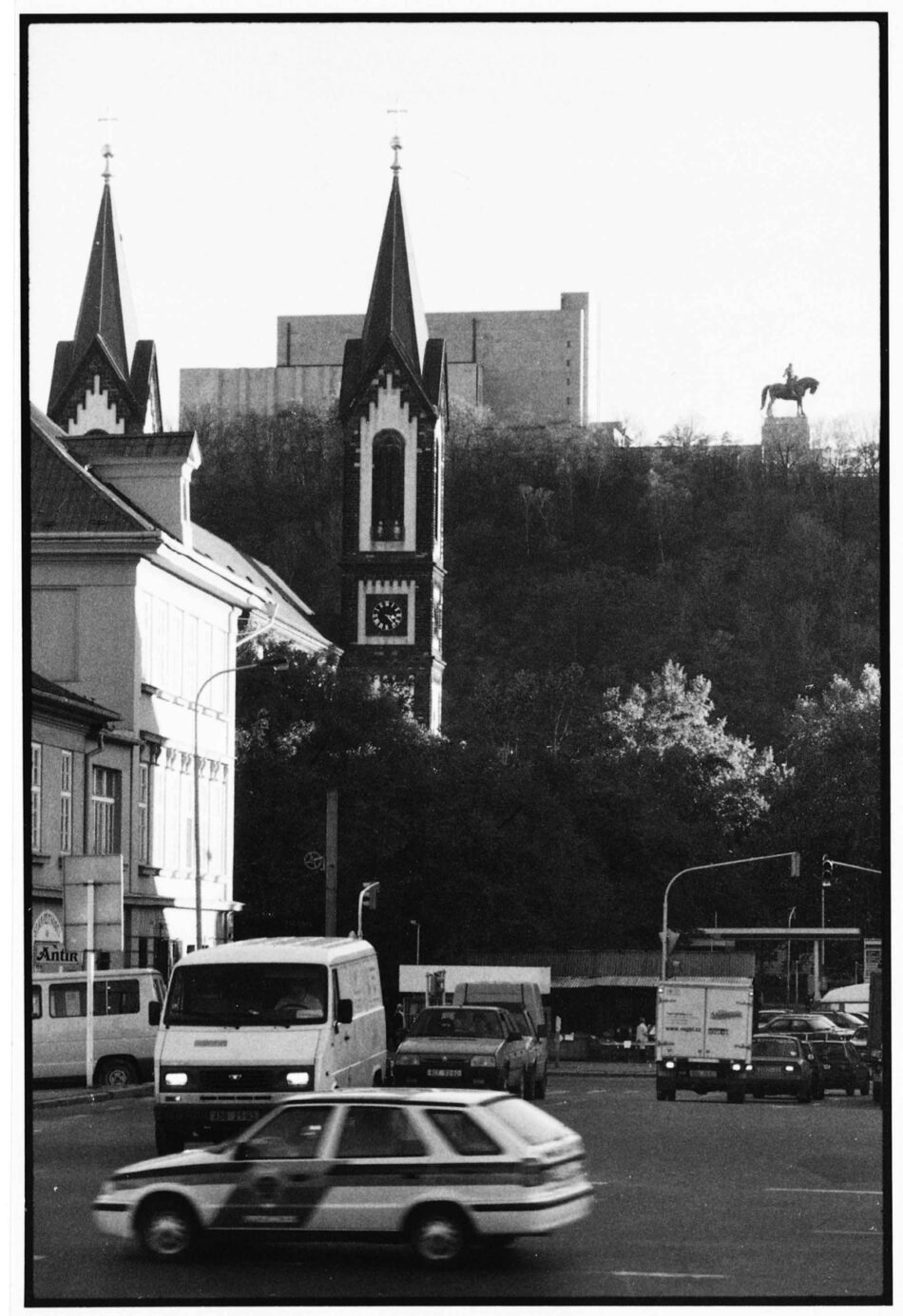

The 1950s became the monument’s heyday due to one critical event above all. This was the decision to install Gottwald’s mummified body in a room within the mausoleum originally reserved for the Czechs’ democratic hero, Tomás G. Masaryk. As leader of the Czech resistance to Austria-Hungary in the First World War and founding president of the Czechoslovak Republic, Masaryk had been provided his own burial chamber at one end of the vast mausoleum on the ground floor. Masaryk, who died in 1937, apparently considered this honor immodest and refused it. No such compunctions troubled Gottwald, however, or his Soviet-influenced entourage. In the logic of Stalinist communism, Gottwald’s interment in the Zizkov Monument confirmed that the struggle for national liberation had culminated not in 1918, but in 1948.

After many months of frantic preparations, Gottwald’s embalmed remains were set on view in December 1953. The space for a subterranean laboratory and control station was excavated in great secrecy, and the entire surrounding neighborhood was rewired to allow for the installation of powerful climate control equipment, in what historian Jan Galandauer has called the creation of “a factory of sorts for the preservation of a dead body.”2 Along with the monument to Stalin on Prague’s Letná plain—another Guinness-record feat of construction—the Klement Gottwald Mausoleum has become fossilized in Czech history as a relic of the 1950s; also like the Stalin monument, its removal in the 1960s has not diminished its presence in the collective memory. Gottwald’s slowly decaying body, which had to be re-embalmed every eighteen months,3 was seen by thousands during its eight years of progressive putrefaction, and childhood memories of yellow-green skin and morbid solemnity persist among many middle-aged people today.

Public awareness that the monument had become a kind of void can be said to date from Gottwald’s cremation in 1962, when the special room that had housed his mummy was emptied and sealed to all visitors. The monument remained an obligatory destination for school outings through the 1980s, and busloads of Soviet visitors were directed there daily during tourist season, but its connection to daily experience was minimal. Meanwhile, in its most exalted function as a welcoming place for foreign heads of state, the Zizkov Monument became a wholly exterior space. Visiting delegations would pause dutifully to lay a wreath at the foot of the state emblem fronting the Zizka statue, then step around the statue’s base to peer through the gates at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, but few people entered the building itself.

The change of regime in 1989, which ended communist rule and paved the way for the creation of the Czech Republic four years later, has rendered the purpose and fate of the building especially uncertain. Clearly at a loss for what to do with the vast complex, the Ministry of Culture and the Zizkov municipality went so far as to lease the monument in 1994 to the robber-baron entrepreneur Vratislav Cekan, who had already scooped up a good portion of the surrounding real estate at fire-sale prices. Spinning out fantastic plans for a hotel and entertainment complex on Vitkov hill, which the press dubbed “the Czech Disneyland,” Cekan meanwhile rented the monument to friends and associates for gala private parties. Fashionably dressed socialites tossing back cocktails and cheese squares in the proximity of sarcophagi that once housed leaders of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic—it would be hard to find a more fitting vignette of the post-communist trivialization of history in the name of consumer capitalism.

Beyond its aesthetic merits and historical interest, the enduring relevance of the Zizkov Monument lies in its ability to assimilate compromise. Like many religious and ruling-class monuments of past eras, this building has accommodated extraordinary changes in its building program that preclude any one-sided explanation of the political philosophies that informed it or the cultural significance it has attained. Moreover, the reversals on Vítkov Hill have taken place rapidly and within living memory, and these shifts give the lie to the building’s very premise: the existence of a unitary “Czech nation.” The traces in the monument of so many contradictory philosophies and ideologies—post-imperial statism, German fascism, Stalinist communism, bureaucratic totalitarianism, and crass commercialism—might be said to highlight, first, the lack of any pristine concept of Czech nationhood in this century, and second, the remarkable ability of the Czech people to emerge from such a series of political transformations with a viable cultural identity.

Unfortunately, compromise is rarely viewed as an asset, and in the case of the Zizkov Monument today, this compromised status seems to many people a distinct liability. Architectural historian Rostislav Svácha has expressed qualified admiration for the building, which he featured on the inside cover of the Czech edition of his ground-breaking survey The Architecture of New Prague.4 In that book, Svácha described Zázvorka reservedly as someone who operated “on the tricky divide between quasi-classical and quasi-Purist idioms,” yet he singled out the pre-1945 decorative scheme at Zizkov as “outstanding.”5 In conversation with me, Svácha reaffirmed his feeling that the building “has something to it,” but said that its architectural impact has been permanently crippled by the many delays and amendments in design before the Second World War and by the host of politically motivated revisions made after the war. Meanwhile, curator and cultural critic Josef Kroutvor, author of an important polemic on the failings of Czech society and many essays on the bygone glories of Prague, shared with me his opinion that the building is fundamentally a precocious experiment in totalitarian architecture. “That whole hill needs to be demythologized,” he added, when I asked how the place might best be presented to the public in the future.

In November 1999, I gained insight into a more expedient answer to this question of presentation when I attended a Veterans Day ceremony at the monument (the first such celebration held in the Czech Republic). Following instructions given by Army Chief of Staff Jirí Sedivy, the hammer-and-sickle held aloft by a statue to the rear of the building had been draped in black cloth, and two socialist-realist haut-reliefs inside the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier were likewise screened from view during the event. As in the fascist and the communist eras alike, for some officials the answer to a historical challenge still seems to be to cover over the symbols of history.

For the past ten years, the physical care of this seemingly endless expanse of granite, lead, and bronze has been the principal responsibility of a single person. This is Josef Dlabac, a sturdily built man in his early fifties, whose generally neutral tone and phlegmatic expression mask a forthrightness rare among those who came of age in the post-1968 period known as “normalization,” the years following the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia, in August 1968. Dlabac has made the monument’s upkeep and promotion his personal concern, evincing a surprisingly even-handed respect for the building’s pre- and postwar contents and a refreshing lack of preachiness on the subject of its historical significance. A trained electrician, Dlabac says he was called to the monument one day in 1975 to fix some faulty wiring, and simply stayed on ever since. For most of the past decade, he has made his office in a dingy basement corner near the front of the main building, now the only continuously heated room in the place. This 200-square-foot subterranean “headquarters” of old carpeting, garage-sale furniture, and piles of cigarette packs could not provide a more extreme contrast with the 34,000 square feet of pristine marble and grandiose decorations under his care.

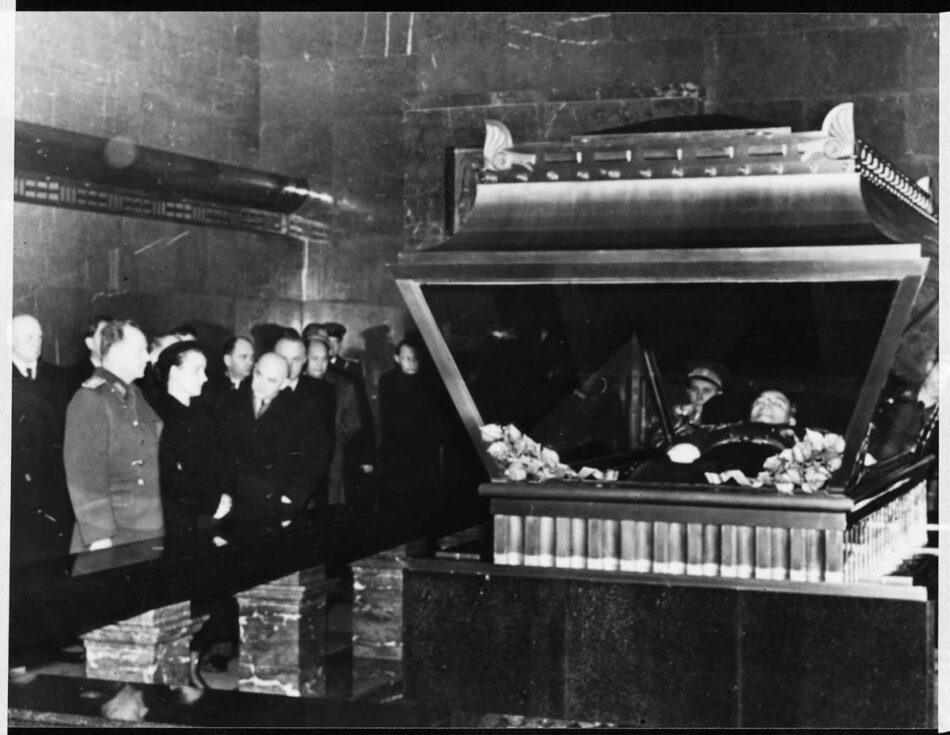

The entrance to the denlike corridor leading to Dlabac’s office is where most visits to the monument begin these days. Such an unprepossessing introduction makes entering the over forty-foot-high main commemoration hall that much more spectacular. Even in a building type known for excess, the Zizkov Monument is overwhelmingly extravagant, with floors, walls, and ceilings laid end-to-end with polished gray and brown marble slabs. Those areas not covered in stone are variously painted in gilt and red, worked with ornate brass fittings, or highlighted by art: most impressive is a wall-length processional mosaic installed above the principal entrance at the east end of the hall. Beyond these arresting surfaces, most viewers are struck by the cavernous scale of the place, and by the dramatic contrast between the quasi-hermetic appearance of the building’s matte granite exterior and the expanse of colors and hues inside, illuminated by a vast skylight.

The front of the main hall serves as an intermediary level between areas of commemoration and celebration. A bronze and glass portal leads downstairs to the mausoleum, while steps to the left and right of this central portal rise toward the main celebration space. The space is impressive in its splendor, and it bespeaks a faith in monumental solidarity characteristic of the interwar period. Rows of short, pewlike wooden chairs upholstered in red leather accentuate the minuscule stature of human beings here, while a gigantic bronze laurel wreath on a massive base of marble heavy-handedly emphasizes the Valhalla-like proportions of the room itself.6 Beyond this main space is the President’s Salon. Like a priest’s inner sanctuary, it is a veritable refuge in its intimacy, with brocade-covered walls, a carpeted wood floor, an oval table ringed by comfortable upholstered chairs, and a magnificent, six-foot-tall chrome heater.

Such Art Deco furnishings and their prewar evocations should make the President’s Salon a popular draw when the monument is reopened. But the most powerful attractions of the site will undoubtedly remain its best-known parts: the mausoleum complex and Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and the Red Army Hall. This last space, planned by Zázvorka in the mid-1950s, may require the greatest political sensitivity in its post-communist presentation. Built to commemorate the Soviet struggle against fascism, it contains the bust of a Russian general, a sarcophagus decorated with the hammer and sickle, and a display case with a Cyrillic inscription commemorating the 1942 battle of Volgograd (Stalingrad). The decision to memorialize the Red Army at the monument deliberately reversed a decision made prior to the coup of 1948 to commemorate Czech fighter pilots, who were now faulted for having flown their missions in the skies over capitalist England rather than communist Russia. Its political history aside, however, the space is successfully proportioned and unified in atmosphere. The larger-than-life mosaics of soldiers and pilots, portrayed with that wonderful socialist-realist blend of idealized youthfulness and utter asexuality, could prove to be as much of a period attraction as the fixtures in the President’s Salon.

The mausoleum is in many respects the most unusual set of spaces in the entire monument, and not just for its association with the body of Klement Gottwald. The principal entrance to this ground-floor complex of rooms leads down a grand marble staircase from the entrance hall, to an area lined with sarcophagi and tomb slabs, all in marble. By locating this room directly under the main commemoration space, Zázvorka aimed for a maximum of piety; his disposition clearly echoes the relation of crypt to nave in a medieval cathedral. The separate burial chamber for Gottwald (originally Masaryk) lies beyond this opulent yet somber space, in between the main building and the Red Army Hall. Meanwhile, a small chamber to the left contains a charming celebration of the legionnaires in the First World War: a mosaic depicting legionnaire activities in the Allied countries, and verses and sculpture of an appropriately reverential tone.

The singularity of the monument’s mausoleum complex, however, is due mainly to the importance accorded here to cremation, a feature that may make this monument unique among Western war memorials. In the 1920s and 1930s, when the Zizkov Monument was being planned and built, Czechoslovakia embraced cremation as part of an enormous drive to throw off old customs and be as modern as possible. By the mid-1930s, cremation was so widely accepted that Czechoslovakia practically topped the list of Western countries using this form of burial, creating a “modern tradition” that continues to this day.7 Thus it is not surprising that the mausoleum complex at Zizkov contains two columbaria, or spaces for the commemoration of cremated remains: one behind the main mausoleum room, and another surrounding the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. In fact, for reasons of hygiene, all the bodies intended for burial at the monument were cremated—even Mr. Gottwald’s, once it had rotted beyond repair.

The emphasis on modernity in the interwar years also influenced the style of public architecture, and its impact at Zizkov is striking. Despite significant modifications, the exterior of Zázvorka’s building retains much of the severity that made it one of the most cleanly modernist proposals of the 1925 competition. Zázvorka’s design distinguished itself in that competition as a spare, minimally inflected container with a flat lead roof, to be constructed around an armature entirely of reinforced concrete—progressive materials for a progressive look. The architect displayed here his appreciation for functionalism, the most radical approach to architecture in Czechoslovakia at the time, even though proponents of functionalism necessarily dismissed the project of a state monument as antithetical to the goals of modern architecture.8 Like the cremation movement, the call for a monumental commemoration of the birth of the Czechoslovak state amounted to an official search for a “modern memorial,” and, for all the compromises that usually hobble state-sponsored endeavors, it is remarkable to see how truly modern the results could be.

Of all the interior spaces, the two columbaria most closely match the bold minimalism of Zázvorka’s functionalist-inspired exterior. Row upon row of white marble squares present a thoroughly blank surface, whose severity of effect Zázvorka underscored by limiting both decoration and color; as such, these spaces intensify a latent chill present in the rest of the mausoleum and the celebration hall above. The blank whiteness of the columbaria absorbs human presence and eliminates it, generating a thrilling but frightful sense of nothingness that ultimately pervades the entire monument. This emptiness predates the hollow rhetoric of 1950s totalitarianism. It emanates instead from the climate of interwar Europe, from that incongruous mix of modernism and commemoration cultivated during the 1920s and ’30s. In their great need both to remember the recent war and to overcome its horrors, “modern” Europeans ironically furthered the abstraction of humanity that made the First World War so chillingly modern in the first place. Utopian visions of a harmoniously mechanized future proceeded from the need to come to terms with the recent, ghastly past—but in their reduction of people to names and numbers, these utopian ideals unwittingly furthered the “statisticization” of human life first practiced on a wide scale with the body counts and mass graveyards introduced during the war.9 The enthusiasm for cremation in Czechoslovakia as a form of “modern commemoration” seems a particularly compelling expression of this paradoxical attitude toward the presence of the individual in society. With a rare concentration of effect, then, the columbaria at the Zizkov Monument—indeed, the entire building—conveys both the possibilities and the pitfalls of historical modernism, and the achievement seems all the more convincing for making the shortcomings so manifest.

During the last three years, as the Ministry of Culture has renewed its efforts to fit the monument into contemporary Czech life, caretaker Dlabac has seen his job expand into the equivalent of all-purpose coordinator. In the first six months of 2000, ten cultural events were held at the site, and the Ministry also reopened the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier for public viewing during state holidays. In addition, the place is increasingly in demand, by everyone from Prague Castle archivists looking to match a textile pattern, to a television crew searching for a space to film a piano concert, to the author of this article, in need of documents for academic research. And yet, despite the energy generated (and demanded) by these requests, the monument as a whole remains a nonsite on the urban map. It doesn’t even have a postal address.

For a native Praguer of the younger generation like Tomás Psenicka, the Zizkov Monument is simply a blank spot on the city landscape. Tomás cannot remember if he was taken to the monument on a class trip or not, and he has only a mild interest in seeing the place today if it should reopen. Like many Prague residents both young and old, Tomás prefers the sumptuousness of the church of St. Nicholas or the endless greenery of the Petrín orchards to an isolated modern building on a hill.

I first met Tomás four years ago, in Philadelphia, where he had come to work at an institute for the developmentally disabled; through photographs and stories he had soon greatly improved my knowledge of entertainment patterns in contemporary Prague. To younger residents especially, the city’s topography is a vast network of bars, cafés, and dance spots, and neighborhoods are distinguished above all by their eating and drinking establishments. With his year and a half in the States, Tomás is fully a part of today’s well-traveled generation of Czech youth, and as a rule he prefers trendy places with a cosmopolitan flavor to the strictly pork-and-dumplings atmosphere of the traditional pubs. This leads us to go drinking in Nové mesto (New Town, but the newness is relative: it was founded in 1348) or Malá strana (the Little Quarter), whose arcaded courtyards and pitched cobblestone streets are home to many lively bars with international offerings.

True to his working-class roots, however, Tomás also has a fondness for the industrial-era grit of Zizkov, and he enjoys beer in the pubs there as well. A crowning symbol of Prague’s late 19th-century economic boom, the Zizkov neighborhood is still associated with labor strikes, large-scale urban expansion, and popular entertainment. During the past several years, the area has become trendy as a place to hear good music and hang out. The neighborhood’s namesake, Zizka, has played a part in this revival—the name of the pioneer postrevolution bar, “The Shot-Out Eye,” alludes to his legendary blindness—and the monument itself has been used increasingly as a venue for concerts and performances sponsored by the Zizkov municipality. Still, the building remains an occasional destination rather than a defining feature of the neighborhood around it.

Nevertheless, plans are afoot once more to “revive Vítkov Hill.” As the new steward of the site, the National Museum is saddled with the task of finding sponsorship for what will doubtless be a multimillion-dollar renovation. Given that the National Museum itself, with its shelves of fossils and historical artifacts, is an institution visited mostly on blue moons, the decision to entrust it with this colossal remake seems at once fitting and self-defeating. In a recent conversation, deputy director Eduard Simek, head of the museum’s history collections, shared a hesitant optimism about his latest responsibility Simek stressed the lovely views visitors will have of downtown Prague from the building’s rooftop, but he refrained from comment on plans for the half-century-old basement morgue. “The site is one Prague residents tend not to identify with,” he admitted with a sigh. The museum will oversee conservation of the entire site, but expects to add exhibition materials in just one room: the only truly empty room, which is, ironically, the former Gottwald mausoleum chamber.

In the meantime, refurbishment of the seven-mile-long park around the building is being undertaken by the Zizkov municipality, where opinions about the hilltop monument are less guarded. “It’s a funereal, cathedral-like building. Who could find a use for that today?” opines Jan Vavrík, an architect hired by the municipality to oversee a public competition to revitalize the area. Vavrík thinks the best solution would include an outdoor café, maybe a picture gallery, and some children’s attraction in the park behind the monument. In Vavrík’s ideal scheme, “eighty percent of the visitors wouldn’t even need to go in the building,” which he finds “architecturally unfortunate” in any case. At the other end of the spectrum is the daydreaming Vítkov Citizens’ Association, which plans to enter the competition with a project to turn both the monument and the surrounding park into a vast, ever-changing exposition devoted to the world’s totalitarian regimes. Armed with the necessary web sites and multimedia aids, this group of young professionals and university students recently held a press conference at the monument to promote their ideas. In attendance were crews from two TV stations, veterans of the Czech resistance, assorted young artists and society types, and two large, shaggy dogs. For many, including the dogs, this was their first visit to the place.

The Zizkov Monument has thus become a projection of a kind of collective schizophrenia. Some people want to focus on its association with communism, while others work at recovering the precommunist dignity of republican patriotism and battlefield valor. Advocates of whatever stripe speak incessantly of “bringing Vítkov to life,” even as they trade on the hill’s centuries-old association with killing and death (a King’s gallows stood on the site well after Zizka did). One institution is now working just on the building, while another focuses exclusively on the parklands around it. The whole place presents “either a terror or a challenge,” to quote a statement made by one official from the Ministry of Culture during the press conference.

In this era touted by some as “posthistorical,” the residue of survival and compromise has no obvious place. Especially in the Czech Republic, where a colossal societal transition is being worked through in fits and starts, tolerance for evidence of transition or accommodation in earlier times is very low. The result is a new kind of absence in Czech culture, a blank space generated by the overnight change of regime in 1989 and reinforced by the contemporary Western focus on the present at the expense of the past. In a world in which the cultural production of earlier eras is appreciated mainly as a museum artifact, and possessed of thousands of architectural structures with proven aesthetic appeal such as castles and churches, Czechs no doubt feel little need to open the Zizkov Monument for international tourist consumption. Still less does anyone wish to consider the importance for Czech society of a building that reflects the strengths and the compromises of the 1920s and ’30s, an era that remains widely revered, and yet manages to do the same for the 1950s, a period that is just as widely disparaged.

It is a singular architecture—and a singular culture—that can survive so many shifts and internal ruptures without vitiating itself. The key to revitalizing the monument will likely be to find a meaning for the place as a whole, and right now such new meaning is lacking. In its place are a number of partial ideas, all of which dance around the vacuum left by an abandoned engagement with history. Luckily, the colossus on Vítkov Hill handles emptiness particularly well. It will doubtless absorb traces of the current debates, too, and assimilate them—inconspicuously—into its marble-clad vastness.

The author would like to thank Janine Mileaf for her careful reading of this essay, and Josef Dlabac, caretaker of the Monument to National Liberation, for his unfailing assistance and personal generosity. Translations from the Czech are by the author.

Matthew S. Witkovsky is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Pennsylvania. From September 1999 through December 2000, he conducted research in Prague on a grant from the J. William Fulbright Commission.