The House of One: Facing Fear

The natural response to terrorism is to bunker down—to increase the thickness of concrete, and expand the distance between public spaces and the fragile institutions within them.1 When our buildings, especially religious structures, become targets, it is tempting to wall them off and reinforce them to ensure that they can withstand explosions.

We bring in police to patrol synagogues and churches, fence off mosques, and incorporate surveillance technology into our sacred spaces. What if we respond- ed differently to terrorism? What if we acknowledge vulnerability, encourage dialogue, and move ahead with the faith that openness and generosity will, in the long run, prevail? Architecture serves as an expression of collective culture, so one would hope that it could facilitate the transcendence of conflict.

This aspiration is central to the proposal for the House of One in Berlin, a project that is all the more remarkable in the wake of the recent attacks in Paris and Brussels. Conceived in 2012 by a rabbi, an imam, and a priest, it aims to build a single house of worship for the three major religions. The three leaders stand firm in their conviction that followers of these religions have more in common than that which differentiates them. They made an overall charter for the center and announced a competition for a new building on Petriplatz, a site with a rich history in the heart of Berlin. It currently shows the excavation of numerous archaeological layers of St. Peter’s Church, first constructed in the early 13th century. Here, the charter envisions a new building as a space for “Jews, Muslims, and Christians to celebrate their faiths and get to know one another together with a mostly secular urban society.”2

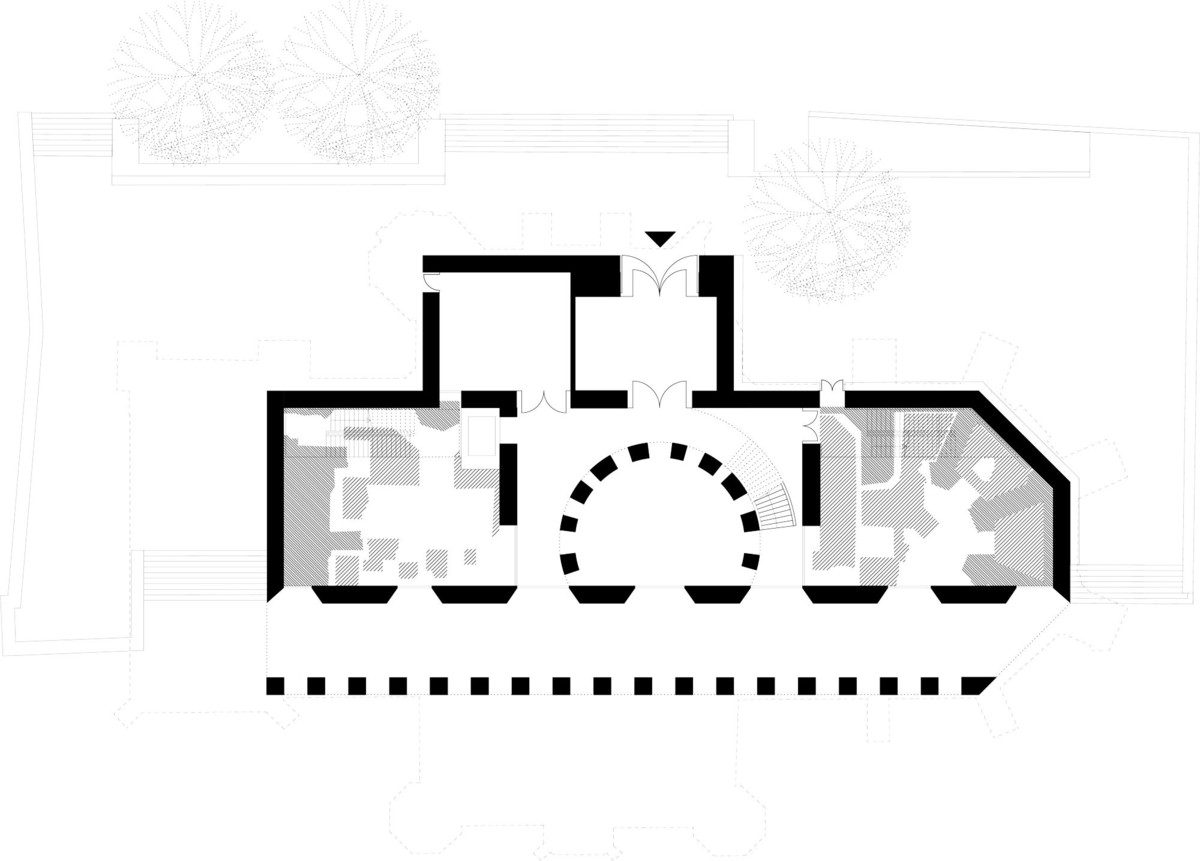

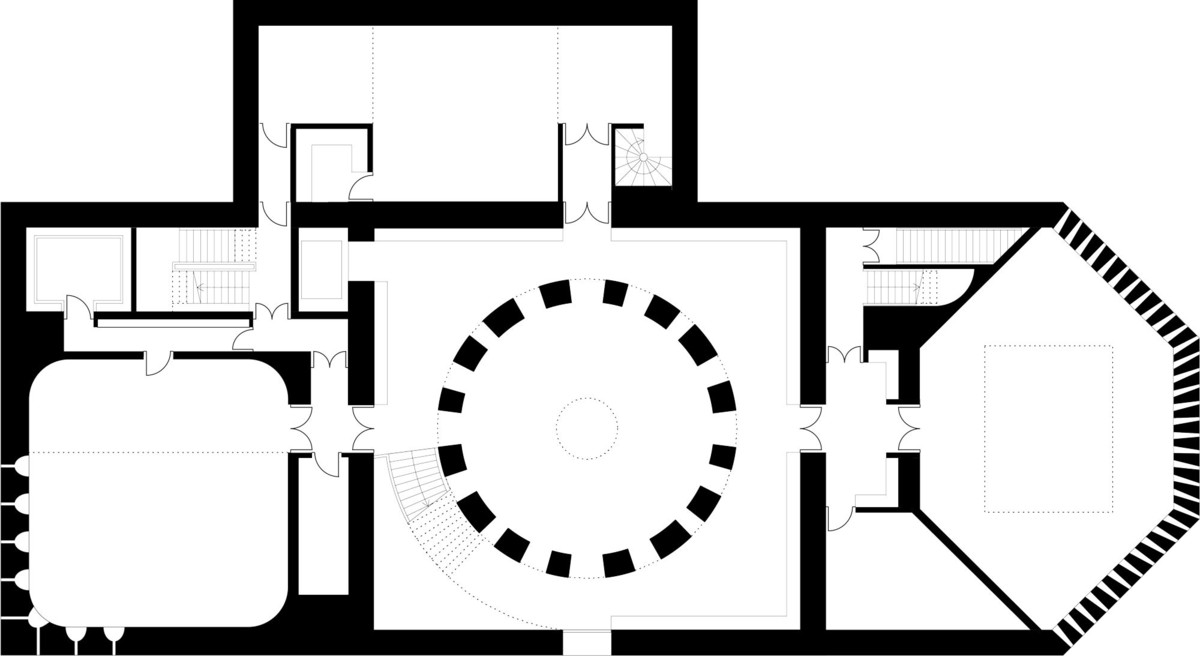

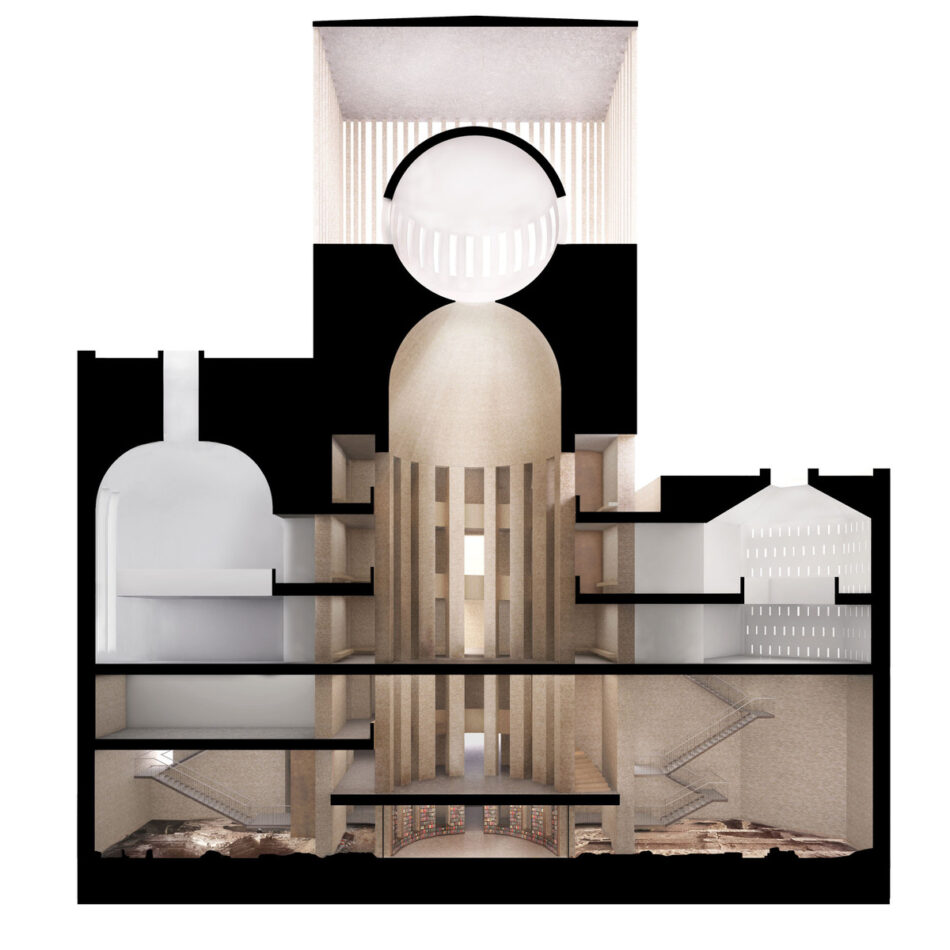

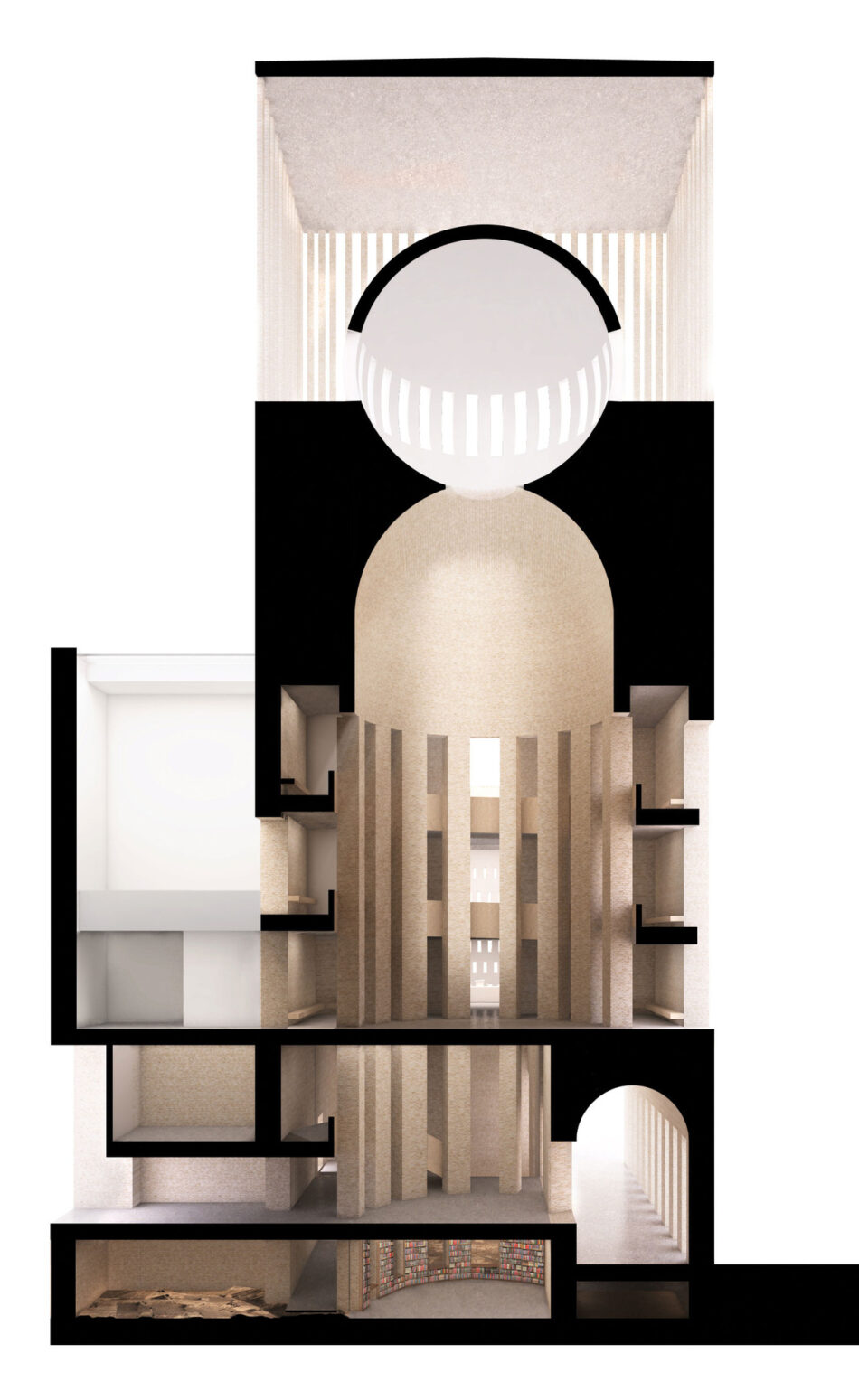

The winning design by Kuehn Malvezzi, a Berlin architecture firm with substantial experience in exhibition design and public spaces, proposes an assemblage of three prayer spaces, each branching off from a central hall. The design maintains the autonomy of each element while requiring some form of interaction: all visitors pass through a communal space in order to access the individual spaces of worship.

The building’s prayer spaces follow their own logic in plan and section, but are incorporated into the conglomerate by a central tower with attenuated natural light filtered through openings in the brick façade and a dome over the circular hall. The height and illumination of the space, reminiscent of the clerestory of classical cathedrals, reinforces the sacral qualities of the building, as do the abstract ornamentation borrowed from traditional mosques and systematic proportions found in older synagogues.

Each of these spaces of worship is designed with an archetypal simplicity and distinct geometry: the square mosque, the rectangular church, and the hexagonal synagogue. The specific characteristics of each space are still being developed in dialogue with the respective religious communities. These differences are not visible from the exterior; they consist of internal excavations from a seemingly monolithic structure. The distinct archetypes have an affinity with the architectural heritage of Aldo Rossi, Giorgio Grassi, and Oswald Mathias Ungers, among others. The writings of Wilfried Kuehn, a founding principal of the firm, attest to this resonance, even referring to Ungers’s 1977 notion of the “City within the City,” which celebrates the diversity of the metropolis and life in general. The logic of colliding distinct realities, founded in part on the coincidentia oppositorum of medieval thinker Cusanus, is “enclosed in one building; a building like a city, inwardly heterogeneous while identifiable from the outside.”3

Facing the Fear

We may be beyond the era in which Herbert Gans could accuse architects (and some of their critics) of suffering from the fallacy of “physical determinism.”4 In other words, the modernist conviction that architecture can encourage or even cause specific behavior by now seems outmoded. Yet the value-free rhetoric of postmodernism has sown its own discontents. In the 21st century, architecture discourse needs a more considered form of connecting societal value and design decisions. This competition entry suggests just that. It seeks an architectural language that espouses societal values such as openness and equality without denying individual difference.

Bricks may not offer moral guidelines, but buildings can reinforce undercurrents of fear and isolation. Concrete barricades, even when subtly disguised as planters, ostensibly give a sense of protection while in reality they wall off and shut out the Other. Architecture has an obligation to express fortitude rather than fear. To refuse to bow down, to seek out beauty and dialogue, and to cherish the fragile connections that build empathy all require true resilience. Bricks offer not only protection but also warmth and a space to gather. The House of One provides typologically distinctive prayer spaces, and courageously binds them.

After the March 22, 2016, attacks in Brussels, the media relentlessly broadcast voices of fear—which is precisely the aim of such attacks. But many interviewees spoke of their refusal to be cowed. Belgians wrote messages of hope and consolation in chalk on the streets of their city. These temporary markings showed the power of our public spaces as connective tissue and platform for expression. The unrest after the attacks was voiced together with the collective choice to resist fear, to acknowledge differences, and to remain in dialogue.

Architecture may not be able to change the world, but it can contribute in small though significant ways. One communal temple, church, and mosque will not prevent future attacks. But it relays an important message of inclusive solidarity to discontented, marginalized souls, and encourages dialogue among those who may not otherwise encounter one another. As a discipline in the public eye, architecture is not merely the provision of shelter but also has the potential to provoke or suggest alternatives. This project is a hopeful gesture, one that seeks a vocabulary of generosity and tolerance over security and intransigence.

1 Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer, “The Architectural Aesthetics of Counter-Terrorism” (conference presentation, Ethics and Aesthetics of Architecture and the Environment, International Society for the Philosophy of Architecture, Newcastle University, July 11–13, 2012).

2 “Charta für ein Miteinander von Christentum, Judentum und Islam” [Charter for a gathering of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam], http://house-of-one.org/en/news-media/downloads.

3 Wilfried Kuehn, “Kuehn Malvezzi Architects, Berlin,” in Religion and Art in the Heart of Modern Manhattan, ed. Aaron Rosen (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2016), 235.

4 Herbert Gans, “Urban Vitality and the Fallacy of Physical Determinism,” in People and Plans: Essays on Urban Problems and Solutions (New York: Basic Books, 1968), 25.

Lara Schrijver is Professor in Architecture at the University of Antwerp, Faculty of Design Sciences, and was DAAD guest professor at the Dessau Institute of Architecture (2013–2014). She holds degrees in architecture from Princeton University and Delft University of Technology, and received her PhD from Eindhoven University of Technology. She is an editorial board member of Footprint and formerly of OASE. Her book Radical Games (2009) was shortlisted for the 2011 CICA Bruno Zevi Book Award.