The Incubator Incubator, the Administration of Leaky Bodies, and Other Labor Pains

The experience of labor is not what your mother made it out to be. Perhaps it was different for her, “back then.” Or maybe your idea of laboring was shaped by movies—a caricature of toiling. Eight hours of hard work or soft discrimination, depending on the occupation. Well, Dolly Parton made it seem like a good time.1

These were paid positions, if underpaid. They weren’t those taken up in a hospital bed or the elsewheres of birthing, if that was the scene you conjured. We are interested in that labor, too, as a frame through which we might also see the waged work that women perform in offices and other interiors of employment.2 “On the clock,” they might express other fluids: sweat, tears, urine, probably menstrual blood, vomit, or maybe milk or cum in other circumstances. These wet things invade the dry zones of professional spaces where women still struggle to find their place, where occupations remain gendered due to the decades-long diversion of women into secretarial and nursing programs and the misogyny that still structures majority-male professions (all which are unconcerned with the administration of care).3 But even as the office becomes amenable to the needs of women at work—in practice and through its architecture—the culture of professional labor has yet to make adequate space for the messes of personal life, which are often collapsed onto the bodies of women.

Valuing Care

As “labor” takes on qualifiers like “emotional” and “interpretive”—beyond sociology and into the post-Tumblr parlance of our day-to-day discourses on life and work—its core definition remains a function of cis-het-patriarchy. “Her labor” still connotes reproduction, wherever it might take place (it can happen anywhere: water broken cartoonishly outside the oikos). Men in labor produce, within a schema of capital that rewards their work as they become increasingly alienated from it. Bullshit jobs abound in late capitalism, the anthropologist David Graeber reminds us, and this alienation of the worker from his labor, hard or otherwise, corresponds to his separateness from the efforts of care, from the human consequence of his work.4 As Graeber writes, “‘Caring labor’ is generally seen as work directed at other people, and it always involves a certain labor of interpretation, empathy, and understanding. To some degree, one might argue that this is not really work at all, it’s just life, or life lived properly . . . but it very much becomes work when all the empathy and imaginative identification is on one side. The key to caring labor as a commodity is not that some people care but that others don’t; that those paying for ‘services’ . . . feel no need to engage in interpretive labor themselves.”5

Men aren’t usually employed to care. It feels bad and pointless to recapitulate this binary, as it does to begrudge the fact of the wage gap. As partners at large firms are congratulated for updating their payrolls, a pregnant Walmart employee is dispensed from the best job she’s had after requesting her maternity leave.6 Our jobs aren’t structured to care about us. And there is no real arc of progress that transports women from the 1950s home to the contemporary boardroom (a narrow aspiration to equity anyway, a Randian triumph over having to care). But workplaces have assumed new forms and protocols to both admit and resist bodies coded feminine, as well as the messes that escape them.

Long after Silvia Federici’s demands for wages for housework in the 1970s, we’ve still not fully grappled with the particular distributions of paid and unpaid labor along gender lines, especially as spatial divisions between work and home have waned.7 Perhaps the impulse should not be to isolate these personal and impersonal forms—reproductive and productive, care and provision—as they are performed by bodied subjects. Rather, we’d like to see reproductive work in the same frame as

paid work: a move that understands the gestation of and care for human bodies as work—work that does not occur outside of the schema of economic production. To the extent that architecture maintains these divisions, we can look to the spatial and logistical measures that place work as a site of potential admission for women, new parents, or nonbinary people: How can offices be remade to support the workforce participation of the underrepresented and underpaid? What other social and productive practices or working subjectivities might be accommodated in new sites of work?

Merely trying to live as women in late capitalism forced us to confront our responsibility to care, and as architects, our directive to produce. In New York City, we found ourselves pursuing an office that could sustain us despite the conditions mentioned above. At this point, and still, we are trying to define our possible situation of work as it delicately and strategically coincides with our friendships, our synced periods, our lives entangled outside of the intellectual and economic contingencies we’ve established through feminist architecture collaborative. We wondered where we could build an office that could accept our messy emotional dependencies, that might one day allow us to support intellectual projects and our personal ambitions, including motherhood. What other professional comforts could we design beyond our economic stability? And what framework would sustain such a “business,” if we must call it that? What we found was a carnival of amenities that were positioned to entertain our immediate comfort but less willing to house our conceptual applications of and to the incubator.

The Incubator Incubator

The Incubator Incubator was one such idea: it would be an office for working mothers, if not an agency for our own surrogacy.8 As we worked toward the underpaid endeavors of feminist creative practice, we thought of ourselves as subjects of incubation and speculated about how our bodies could be at work in other ways to support ourselves—even and especially laid out in some appropriately cushioned room. The nested incubator, a retrofit of available coworking space, could include the infrastructure of a medical suite or spa, a heightened amalgam of the services already available to soft bodies in metropolitan centers (hyperbaric chambers, cat cafés, your basic curtain-partitioned massage joint). Beyond the small and immediate fantasy of maximizing our comfort, we lingered on a concept that might someday manifest the greatest ambitions of flexible work: the premium accommodation of a shambles (our soft bods or a business-in-formation).

In New York City, the incubator is one among many outposts where business resources are pooled to provide temporary support.9 There, work space is just one amenity among others that aids in productivity toward solvency. Wet labs, fabrication shops, shared kitchens, and chill-out zones append the expected array of offices and meeting rooms. This infrastructure for starting up—some configuration of hot desks around a router—is still discussed as an emerging workplace, but it is rapidly defining the status quo for contemporary variations on the office. A sibling of the coworking space, the incubator is a more or less established zone for companies-in-becoming, companies without real estate, and those too young for Human Resources. It hosts visiting hours for potential investors in open-plan offices with plush furniture, tropical plants, MakerBots, Aesop soaps10 and other accoutrements that aid in the procreation of new business and new money.

As menstruators, migraineurs, and architects not given over to the sadomasochism of overwork that the architecture profession encourages, and on which it depends, we felt that our perversion of incubation could drive us from the ills that have been propagated by the conventional workplace and renewed through start-up culture.

Workplace Feminization

The struggle toward the greater employment of women corresponds to accommodations made for them in the workplace, those authorized by men, who deigned to provide us with desks and a ladies’ room. Triggered by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, the “feminization” of labor had to grapple with the logistical problems posed by an office that was set up for men.11 Women who joined the ranks of associates were made to take their desks in the pen of secretaries, to force their proper place in support and not in power. In the woke working world of 2018, that integration is no less conspicuous. In some offices, the infrastructure that admits and obliges women has expanded to include curious artifacts like the lactation pod, which visibly houses our leakiness. It is a container for maternity in the company of others.

We might be asked to see the pod—a defamiliarizing architectural expression of breastfeeding—as a nicety of the feminized workplace. With all the futurity implied in the incubator and the “new office,” this furniture situates the promise of equity and flexibility as a negation of a specific body at work. Her biological material, the evidence of her other attachments, must be contained within a conspicuous island in the office of yore or in a hot new specification in the offices to come.12 Until then, she might rather just stay home, pump topless, and answer e-mails while the babe sleeps.

The admittance of breastfeeding into the space of work via the pod reinforces the regime of neutrality—a requisite “best,” “many thanks,” or “kind regards”—that delimits production against human improprieties. Her “inappropriate” act is served primarily by a concealing wall: it’s an outside produced inside, hidden by a surface with no depth. Seen and read by men as “nothing happening over there,” the pod houses the act of pumping and feeding within the workplace, but it is

nonetheless rendered illegible.

The expression of milk is one of many possible flows that must be stemmed or hidden away in order to prioritize paid tasks. The new mom is one figure whose needs we’ve agreed to tolerate, and, as a consequence, she is less desirable as an employee.13 But for the rest of the leaky workforce, shall we institute pods for crying? For sweating? Free bleeding? These activities are relegated to bathrooms that may or may not be outfitted to accommodate such expulsions. Places to dispose of your spent tampons, to dump out your menstrual cup (not in a stall situation!), to inject your hormones, to apply concealer over the cyst you nervously picked at, to rub Tiger Balm on your shoulder knot, to mop your brow, to attend to all the unsightly measures of caring for your own body that might make you appear less capable of doing the job you were hired for. We spend time suppressing these habits in a culture of work where errant bodily conditions can be disqualifying. And so we put a partition between them and our computer screens.

In her essay on the gendered shame of our unruly fluids for the New Inquiry, Emma Pask suggests the productive power of leaking to be gained through a shift in culture—one that can be traced from the humoral tradition of the 17th century to the contemporary assignments of the trans body: “While we push to make medical and legal systems recognize the biological reality of our leaky bodies, can we, in the meantime, have a more intimate relationship to our menstrual blood, our orgasms, our sweat, and our tears? These leaks can represent the multiple ways we stay in flux: Periods show time passing, orgasms demonstrate sexual growth, sweat and tears exhibit hard work.”14

The messes that betray growth or hard work aren’t yet permitted by the architecture made to accommodate our productivity. The enumeration of the office’s needs and protocols are imagined by men—who are still overrepresented among the ranks of architects, COOs, accountants, and building managers. They decide if a receptacle for “feminine hygiene products” should be installed. The culture that rewards men and disadvantages women continues to play out in the architecture of work, which enforces gender inequality. It makes sense to pursue retrofit as an avenue toward cultural shift, but we must also examine the ways in which these designs defer progress through the provision of glossy surfaces.

Lactation pods assert themselves in the hallways of metropolitan institutions. The all-gender bathroom appears as a sign on doors to single-stalls. We have asked for these things; they have been insisted upon by diversity commissions, by architects pushing new CAD blocks, or by some enterprising ally in a position to implement change. In serving the needs of non-cis-male workers, new pods, partitions, and signage visibly seal away all that we must suppress as private and bodily. But privacy is still a necessary provision, especially for employees whose biological materials are subject to much closer scrutiny than cisgendered white women. Pask reminds us that the indignity of leaking bears more urgent consequences for people of color, indigenous people, and trans people: “Medical and legal systems exploit their bodily tissues and liquids to make claims on their autonomy: People of color are wrongfully accused of crime through dodgy biological evidence, indigenous people are required to prove their heritage through blood samples, and trans people are unable to find legal representation with a new name and sex identity, to name a few examples. The hurdles set in place to demonstrate innocence, prove identity, and authenticate sex can be degrading and violent. Leakiness is not just undignified; it can also be unsafe.”15

No equity has yet been achieved, least of all for women of color, and global capitalism carves out shittier niches in which women can find work. But in economic centers like New York, educated people in the “creative class” are being presented with workplace products in new shades of hospitality—spaceships for breastmilk included.16 Among the suite of products that enable self-care against the exhaustion of overwork, it seems more probable to consume our own better treatment. But if such treatment is only accessible through membership, as amenities, it only compounds the exploitation of those who can’t afford a better situation, which can only be elective and never deserved. It’s hard to ask for equal pay for equal work. It feels much easier to ask: “Where’s my fucking spa?” Is there any political power to be found in demanding our needs as a service, as opposed to a right?

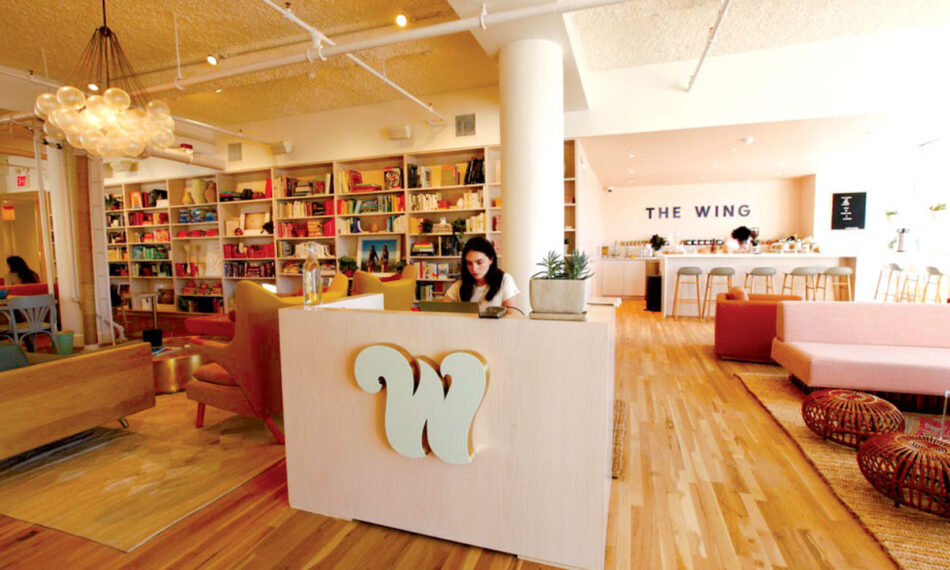

Like the venture capital portfolios segmented for investment in lady-biz, we actually do have a cowork of our own—and it is nice. The Wing is less concertedly a place for work; rather, it’s a “home base and social club” arranged exclusively for women—a No Man’s Land, as the title of its in-house publication asserts. This exclusivity is not simply mandated but is, instead, thoughtfully built.17 Its New York flagship location was designed by women—the architect Alda Ly and the interior designers Chiara de Rege and Hilary Koyfman—with women’s needs in mind. As one writer puts it, “the whole place is a kind of ladies’ room.”18

The designs of the Wings in New York, San Francisco, and Washington, DC, attend to its mission: the “professional, civic, social, and economic advancement of women through community.”19 Washes of pink, velvet couches, and soft lighting lend to an atmosphere of femme pleasure, which enables a particular kind of coming together. The aesthetics of womanly company in the Wing is entertained as a political question, reinforced equally by its decorative products and by the discrimination investigations into the club in New York. According to the New York City Commission on Human Rights, the exclusion of men from pink offices is more egregious than all those hostilities that would drive women from “feminized workplaces” in the first place.20 So far have we come that we’ve had to resuscitate the 19th-century women’s social club.

But, in paying for the safe articulation of our own ambitions, women who can afford membership dues are alleviated from the latent misogyny of mixed companies; presumably, at the Wing, they join to care for each other. But we wonder how all those women employed to maintain the sparkle of such an environment—to mop up spilled lattes and such—locate themselves in relation to the coven, to the inside that permits women to do “whatever the fuck they want.”21 Certainly, this is a reality of capitalism in which our liberal lady guilt is suspended, the knife’s edge on which we seek safe space and are made to pay for it. As if the women cleaning the bathroom aren’t paying for it in some other way. The same shitty dynamics of feminization and late capitalism are reproduced in the cowork of our dreams, not sealed off from it. There’s no safe space, but that doesn’t make it any less necessary.

Human Capital, Matrixial Relations

It’s no wonder that women and all those underserved by the infrastructure of the office (queer and trans people, those with disabilities and invisible chronic conditions) would rather work from home and for themselves than take part in negotiations of their own security, comfort, or humanity.22 If what we’re really seeking is the antidote to the activities that diminish the body, shape it into more profitable molds, and orchestrate its physical and cognitive efforts around scheduled tasks, then the most legitimate disruption of work is medical.23 Rehab, inpatient care, specialist appointments, and doctor-mandated bed rest are permissible sites of exemption from work, where we might retreat out of expectation or necessity. In the interim of work, personal forms of labor (getting well, giving birth, caring for loved ones) can proceed. We take the leave that is owed to us and that ensures we can return to productive positions.

To the extent that one’s job determines if, when, and how we are able to take time off to pursue “real” care, it’s worth examining the cultural currencies that flow between caring as profession, as gendered responsibility, and as technology. We might then look to the hospital as an architecture charged with the administration of care, both technological and social. Katie Lloyd Thomas writes about these extended relations, particularly in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), where ectogenesis is designed to replicate the delicate supports of maternity through a socially, materially, and spatially diverse set of matrixial relations.24 Literal incubators, made to support the underdeveloped bodies of premature babies take the place of the work of the body, warming, nourishing, and protecting them from an inhospitable outside. Meanwhile, mothers stand attendant to this care, part of its mechanism, but helped by so many other supports: human resources like nurses, doctors, specialists, orderlies, and doulas, and the technical implements that keep little bodies breathing. Here, professionalization reconfigures care that has long been essentialized as biological or innately female. Women alone are not responsible for reproductive work, and the NICU is an object lesson in how other entities can be orchestrated to help.

In the same way, care might be, in part, deferred to the organizations that employ us, if for no other reason than to ensure the perpetuity of production. HR, corporate and otherwise, must be transformed from a pool for extraction into an ecosystem that propagates the health and happiness of its employees. The vulnerability that characterizes leaking may be the most definite flag to its attentions. Caring for the body at work is a way of identifying its incompatibility with all the pressures of late capitalism that act on it, as with the administrative mechanisms that dispatch children of migrants into detention centers run by Health and Human Services. Humans are the alien entities that make up flows, primarily of capital. There is an urgent need to be tender to these pains felt by the body that are made precarious by financial and juridical systems. Otherwise, a nanny state incurs into our personal lives with no support—maternal or otherwise—for personal matters.

The hospital is the remand of the temporarily unemployable, where, like the new office, its spaces have been redesigned for contemporary comforts, privacy, and classed levels of care. It is professionalized to make its patients’ un/paid, legally protected time off as efficient as it can be, either for the doctors juggling patients or for the women who are able to design their birth experiences. In this context, birth can be made both expedient (think of the number of C-sections that happen in a given ward on the day before some obstetrician goes on vacation) and equipped for one’s leisure (with features such as en-suite bathrooms, dimmable lighting, and room service). Labor can be hastened by a Pitocin drip and alleviated by an epidural. The executive birthing suite at New York’s Lenox Hill Hospital was closed off for the delivery of Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s first-born child, Blue Ivy.25 Women empowered to do so take leave, of work and the hospital, in alternate configurations for their labors, including doula-attended blow-up pools in Palm Springs clinics. At the same time, in the United States, black maternal mortality rates are surging.26 Birth is subject to the same have-it-all capitalism the office propagates, only with different deliverables. How, then, is the pregnant body still abject in those spaces, a hovering dunk tank of amniotic fluid ready to douse some middle manager?

WeWork toward Emancipation?

We must find ways to attend to these needs in a manner that might reposition the culture of work that elides, erases, and reduces the body. Where can we incubate a political future that we are told is female?

In the flashy marketplace of ideas that values the disruptive, the new, or the unforeseen, we situate the matter of our bodies—full of blood and life and bile—as the transgressive occupants of enterprise. You must accommodate us. You must pay for it. There’s no amount of “leaning in” that can adjust the culture of work to not be a domain suited to men. The architectural substrate that secures this domain must shift to reformulate the classing of caretaking. In alliance with strippers’ unions, Russian surrogates, border clinicians, migrant moms, and all the part-time biddies and “casual employees,” we have to refuse the niceties that only briefly attenuate our exploitation. No longer involved in production but service in the expanded view, we must implicate all people, entities, and regulatory mechanisms in the production of care. The space of work is the sociotechnical medium by which change can be made

and enforced as design guidelines, as the coded provisions of the Family and Medical Leave Act, in the break room, and in the menstrual suite. We’re taking our break now. This is our notice.

moment they marry and have children, caring for others, especially over the long term, requires maintaining a world that’s relatively predictable as the grounds on which caring can take place. . . . And that, in turn, means that love for others—people, animals, landscapes—regularly requires the maintenance of institutional structures one might otherwise despise.” Ibid., 236–39. 6 In the United States, the Family and Medical Leave Act requires private companies with more the 50 employees to provide unpaid, job-protected leave to employees of more than

12 months. The Department of Labor describes other eligibility requirements here: Need Time?: The Employee’s Guide to the Family and Medical Leave Act (June 2015), https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla. The case of Walmart employee Otisha Woolbright is discussed alongside those brought by women at other private companies who have faced pregnancy discrimination in the United States in Natalie Kitroeff and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, “Pregnancy Discrimination Is Rampant Inside America’s Biggest Companies,” New York Times, June 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/06/15/business/pregnancy-discrimination.html. 7 See Silvia Federici, Wages against Housework (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1975). 8 What broke grad student with unoccupied ovaries hasn’t considered selling their eggs to pay down their student loans? It surely isn’t us alone. 9 New York City’s Economic Development Corporation publishes a list of city-supported incubators and coworking spaces as a public resource for startups. See “Incubators & Workspace Resources,” New York City Economic Development Corporation, https://www.nycedc.com/service/incubators-workspace-resources. 10 This is one branded feature promised by NeueHouse, a New York- and Los Angeles-based coworking space designed to be hotel-like in its amenities. 11 “Feminization of labor is a term that describes emerging gendered labor relations born out of the rise of global capitalism. It is feminization of the workplace, which is a trend towards greater employment of women, and of men willing and able

to operate with these more feminized workplace [sic]. Feminization of labor is a result of expansion of trade, capital flows, and technological advances. Gender discrimination, violence, sweatshops, and sexual harassment are some of the adverse results of feminization of labor. Multinationals prefer women in the labor force as women have . . . long since worked for lower wages and are less likely to organize.” “Feminization of Labor Law and Legal Definition,” US Legal, https://definitions.uslegal.com/f/feminization-of-labor/; italics ours. The Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 follows other landmark antidiscrimination legislation in the United States beginning with the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1965. This model policy propagated similar legal efforts around the world to prevent discrimination in the workplace and elsewhere. But the global reality remains that women still face gender-based restrictions in pursuing formal employment. See Gayle Tzemach Lemmon, “Lack of Law Breeds Workplace Discrimination,” Council on Foreign Relations, September 18, 2017, https://www.cfr.org/blog/lack-law-breeds-workplace-discrimination. 12 See Murrye Bernard, “Priming the Pump: Lactation Room Design Guidelines,” Architect, August 2, 2018, https://www.architectmagazine.com/practice/priming-the-pump-lactation-room-design-guidelines_o. 13 This type of workplace discrimination can also be found in our beloved cultural institutions. See Melena Ryzik, “Curator Says MoMA PS1 Wanted Her, Until She Had a Baby,” New York Times, July 6, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/06/arts/design/moma-ps1-discrimination-suit-baby.html. 14 Emma Pask, “Becoming a Leak,” New Inquiry, May 30, 2017, https://thenewinquiry.com/becoming-a-leak/. 15 Ibid. 16 Women hold a slight majority of jobs within the “creative class,” which includes everything from architecture to nursing, but they still make significantly less than their male counterparts. The 2011 study “The Rise of Women in the Creative Class” controlled for education and hours worked to find that the pay disparity was lower in male-dominated fields like architecture and engineering (about $9,000 annually) than in professions with majority women, like nursing. See Richard Florida, “The Income Disparity of Women in the Creative Class,“ CityLab, November 2, 2011, https://www.citylab.com/life/2011/11/income-disparity-women-creative-class/359/. 17 “True gender equality requires a good deal of new construction. Materials were selected to optimize female comfort, furniture would be suitably proportioned; there would be spaces to socialize and others in which to retreat. A separate ‘Beauty’ room was to be walled off from the toilets, for relaxed primping.” Betsy Morais, “What Does a Workspace Built for Women Look Like?,” Atlantic, April 12, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/04/an-architect-for-the-feminist-moment/557516/. 18 The Wing’s special attention to the temperatures and restrooms demonstrates its emphasis on the bodily comfort of its anticipated occupants. “[T]he clubs have been kept between 73 and 74 degrees, appreciably higher than New York’s mandated temperature of at least 68, and flouting typical guy-bod preference. (The Wing’s contractor, a man, still has a habit of lowering it to 70 when he comes by.)” Ibid. 19 “About Us,” The Wing, https://www.the-wing.com/about/. 20 Amanda Arnold, “The Wing Is Under Investigation by the New York Human Rights Commission,” Cut, March 27, 2018, https://www.thecut.com/2018/03/the-wing-discrimination-investigation-human-rights-commission.html. 21 The Wing solely employs women among its ranks of designers, community coordinators, facilities managers, and kitchen staff. Their swag, sold online and by shopgirls at various locations encourages the women of the Wing—members or otherwise—with a choice mantra: “Girls Doing Whatever the Fuck They Want in 2018,” https://shop.the-wing.com/products/girls-doing-whatever-in-2018-tee. 22 See Emma Jacobs, “Gig Economy Offers Risks and Rewards for Transgender Workers,” Financial Times, October 24, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/2cf4b078-91f5-11e6-a72e-b428cb934b78. 23 For example, the positioning of maternity as a medical condition was decisive in how workplace pregnancy discrimination lawsuits are adjudicated. 24 Katie Lloyd Thomas, “Incubators, Pumps, and Other Hard-Breasted Bodies,” in Undutiful Daughters: New Directions in Feminist Thought and Practice, eds. Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni, and Fanny Söderbäck (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 113–25. 25 Nina Bernstein, “After Beyoncé Gives Birth, Patients Protest Celebrity Security at Lenox Hill Hospital,” New York Times, January 9, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/10/nyregion/after-birth-by-beyonce-patients-protest-celebrity-security-at-lenox-hill-hospital.html. 26 Linda Villarosa, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis,” New York Times Magazine, April 11, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html.

feminist architecture collaborative (aka f-architecture) is a three-woman* architectural research enterprise aimed at disentangling the contemporary spatial politics of bodies, intimately and globally. Their projects traverse theoretical and activist registers to locate new forms of architectural work through critical relationships with collaborators across continents and an expanding definition of Designer.

*Gabrielle Printz, Virginia Black, and Rosana Elkhatib maintain their wily practice and their deep friendship in Brooklyn, New York.