Willi Smith, WilliWear Map Print Skirt, Summer 1986 Collection

I had been researching American designer Willi Smith for a year before finding this skirt late one night during a deep-dive on Instagram. It appeared on the feed of a San Francisco–based vintage dealer, a major discovery buried amidst crop tops and mom jeans. When Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum began organizing the Willi Smith: Street Couture exhibition in 2018, we were faced with a fundamental problem: we couldn’t find examples of Smith’s designs. The curatorial team desperately sought WilliWear made between 1976 and 1987–the period during which Smith led his company before succumbing to HIV/AIDS at age 39–calling friends, family, collaborators and museums.

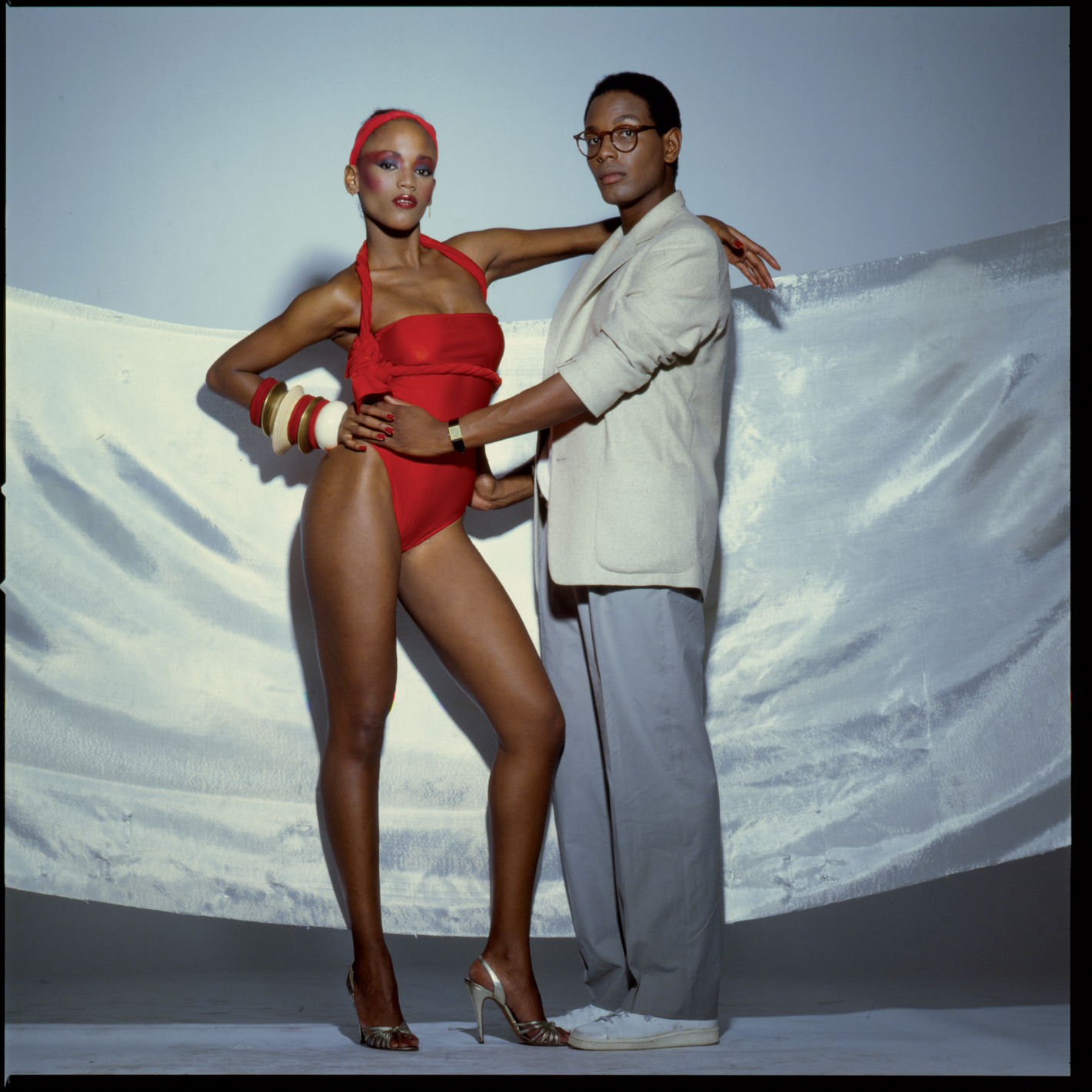

Again and again we heard, “I wish I still had my WilliWear, but I wore it out,” conjuring images of beloved garments put to work on sidewalks and dance floors. Smith, no doubt, would have relished the idea that his designs ended up decommissioned in tatters. After all, WilliWear was not really about fashion, per se; it was a brand aiming to connect with American culture. Smith saw that fashion codes of the time restricted people’s identities: working women, the Black middle class, queer communities, artists, socialites. He and his partner Laurie Mallet created affordable clothing that was both utilitarian and carefree—“canvases for the body that you can dress up or down.”1 As peers such as Giorgio Armani, Pierre Cardin, and Ralph Lauren (who famously uttered “I don’t design clothes, I design dreams”) produced fantasies, WilliWear made clothing to fit diverse lifestyles.

Versatility, even anonymity, defined most of Smith’s “basic” designs, but he punctuated collections with evocative patterns. The patterns, found on garments, graphic materials, and publications, carried messages that alluded to Smith’s research, values, and identity. He drew coy smiles into Malian bògòlanfini prints rendered on skirts,2 wrapped heads in colonial-export gingham, and cascaded his trademark round glasses down jumpsuits and dresses.

For his 1985 and 1986 collections, Smith tried something new—focusing on black and white. Jeff Tweedy, former head of womenswear for WilliWear and current CEO of Sean Jean, remembers that the aesthetic was inspired by Smith’s trip to Senegal to shoot Expedition, a pioneering fashion film.3 Expedition embodied Smith’s growing interest in connecting with his own heritage while encouraging his audience to explore African cultures. According to Tweedy, Smith returned elated from the shoot in Dakar: “It was just this moment of happiness of discovering what Africa was all about. It changed his creative perspective on the 1985 collections and those after. At the time, designers weren’t going to Africa for inspiration, but he did.”4

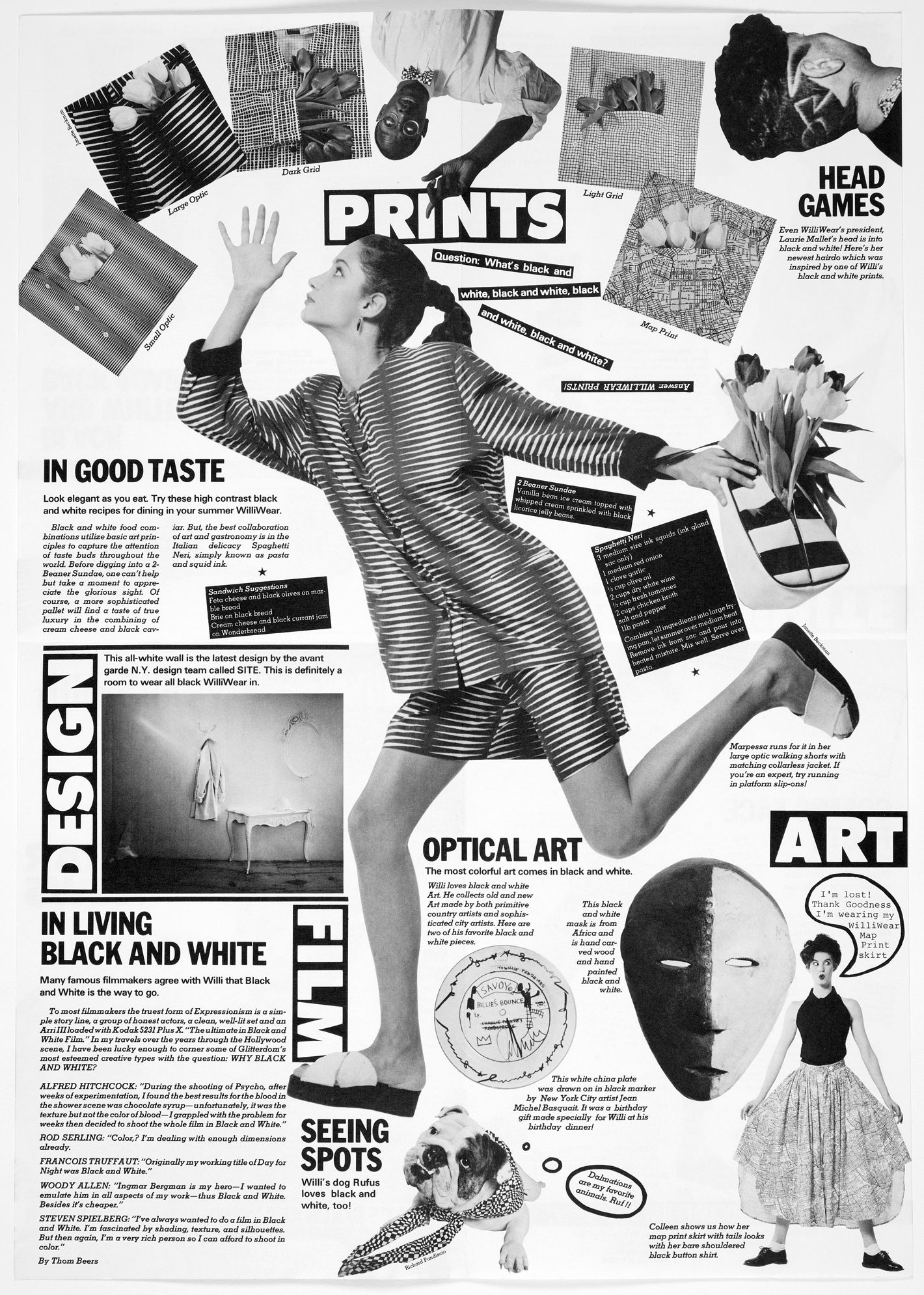

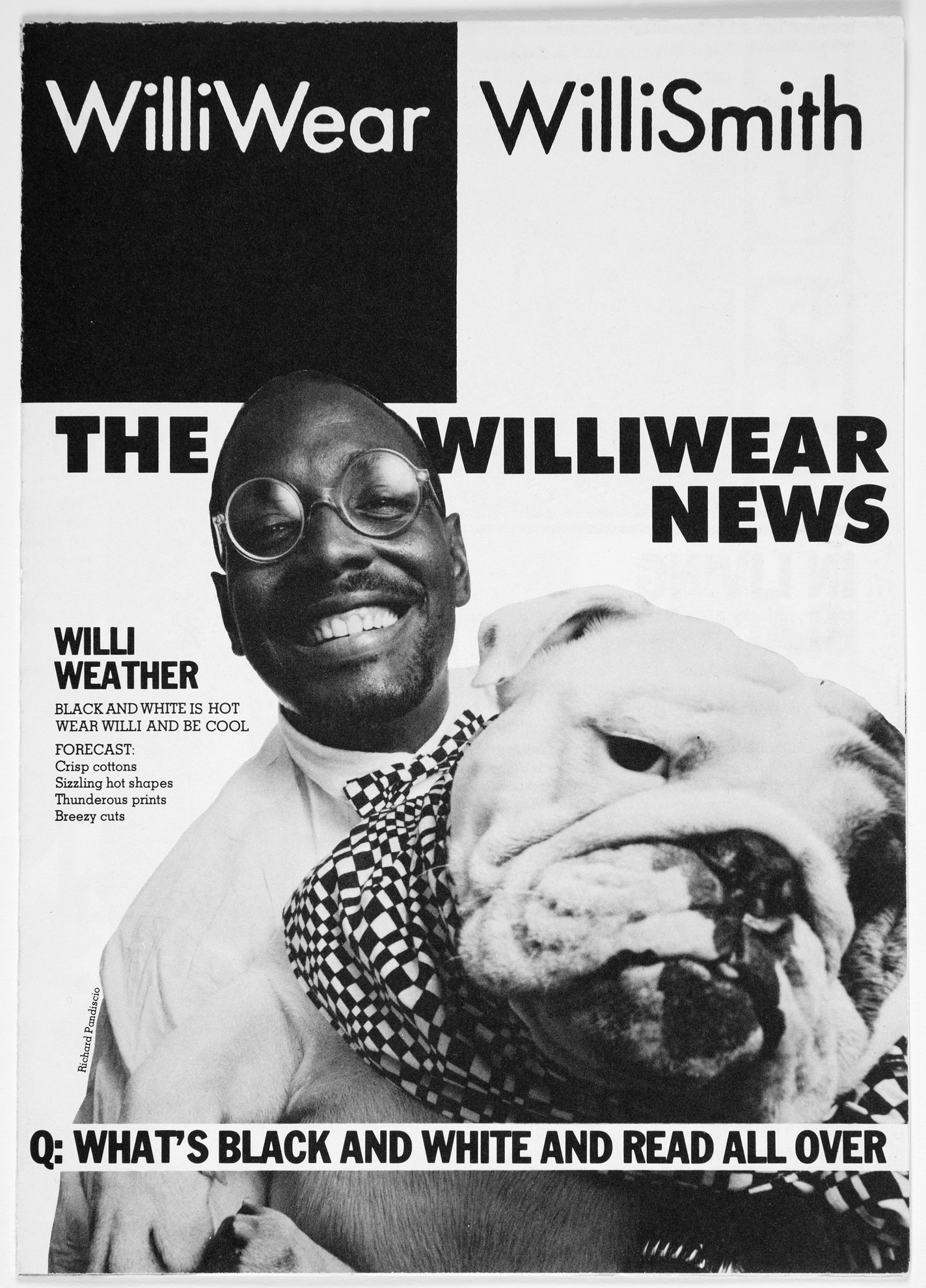

Tweedy noticed that Smith began embedding more complex and abstract symbols in his designs. He incorporated shapes and compositions familiar to artists in his cohort including Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Dan Friedman. He referenced a hand-carved Dan mask acquired in Côte d’Ivoire, as well as the portraits of photographers Seydou Keïta, Mama Casset, and Martine Barrat. In a 1986 issue of WilliWear News published by Paper Magazine, black-and-white expressions in film, food, art, and design endorse a playful cultural context for the Summer ’86 Black and White OPTIC collection: “Black and white is hot. Wear Willi and be cool.”5

In an interview with New York Times fashion critic Bernadine Morris, Smith called the diffractive and repeating patterns employed throughout the collection “Urban Optics”—a phrase evoking geometric camouflage for a concrete jungle. The patterns were conceived with Martha Nutt, a young Rhode Island School of Design graduate, whom Smith hired as an in-house textile designer after falling for the moiré optical patterns and fabric grid motifs populating her portfolio. Nutt’s sketches were translated into black and white for the collection; then, together, they conceived of the WilliWear Map print, a grid on repeat to be executed in black pigment on white cotton poplin. The print was used for various garments, including a voluminous skirt with extended back and front panels reminiscent of an early modern-era tailcoat. The silhouette of this Map print skirt with tails exemplified Smith’s characteristic deconstruction of Western fashion binaries: men’s and women’s apparel, uniform and civilian dress, formalwear and streetwear.

At the time, Smith’s company was about to gross $25 million in annual sales, making him the most commercially successful Black designer in history. This mainstream achievement relied on Smith’s resistance to outwardly transgressing social norms. He had learned to code-switch between a nonchalant public persona and the freedom of his tight inner circle after Parsons expelled him in 1967 for being openly gay—an act of censorship that matched repressive tactics within the wider industry. Even Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé’s epic partnership was a secret at the time, if an open one. But as Smith’s market share grew, so did his revolutionary consciousness. He increasingly wove anti-racist and inclusive messaging into his work: dressing the dancers in Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company’s Secret Pastures;6 staging a runway show at the Rikers Island women’s prison; designing a “nannies and chauffeurs” Fall 1986 collection quoting colonial dress; appearing in Expedition in drag.

The WilliWear Map print underscored how Smith playfully packaged meaning in his product. The chosen map adapted a section of South Flushing, Queens, in repeating grids, including the sites of the 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs, and a series of parks, botanical gardens, and cemeteries that were mined, landfilled, and landscaped by Robert Moses and private developers for most of the 20th century. In the central grid, Smith renamed Kissena Park, the former home of a 19th-century exotic tree nursery that was once intended to become the Central Park of Queens, as WilliWear Park. With this gesture, Smith appropriated a historic tool of control and segregation. He colonized Queens with eraser and pen in the manner of monarchs and politicians, branding the territory where nations once showcased their prejudicial triumphs.

Smith’s subversions often had the feeling of an inside joke—most of his consumers would not recognize the meaning layered on their bodies—but their significance for those actively disenfranchised by social norms cannot be ignored. In Expedition, Smith satirized the imperialistic exclusion of an airport customs search: Dakar locals dressed in vibrant WilliWear escape—clown-car style—from a steamer trunk, take a bathroom break, then climb back in, undetected by an oblivious border official (played by Smith). The artist Brendan Fernandes proposes that this scene, and Smith’s projects in general, model scenarios for people of color to navigate traditionally white spaces: “Smith’s work suggests that while mere visibility can be humiliating, even dangerous, hypervisibility can be a strategy for both subversion and survival.”7 In this light, the Urban Optics of Smith’s Summer ’86 collection emerge as an attack against colonial agendas.

“I’m lost! Thank goodness I’m wearing my WilliWear Map Print Skirt!” exclaims a model, Colleen, in that Summer ’86 issue of WilliWear News. When interviewed in 1973 for Fabric News, Smith explained that he wanted “to help people through clothing solve the problem of getting dressed.” This statement, perhaps more than any other, outlines the project of WilliWear: to embolden people to find themselves and find their way. “Getting dressed,”8 especially for marginalized communities, involved preparation for risky situations. Through the hypervisibility of his Urban Optics, Smith forged a new tactic for liberation. One that continues to resonate in our country’s enduring white-supremacist landscape.

ALEXANDRA CUNNINGHAM CAMERON is the curator of contemporary design and Hintz Secretarial Scholar at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York.