The Right of the People Peaceably to Assemble in Unusual Clothing

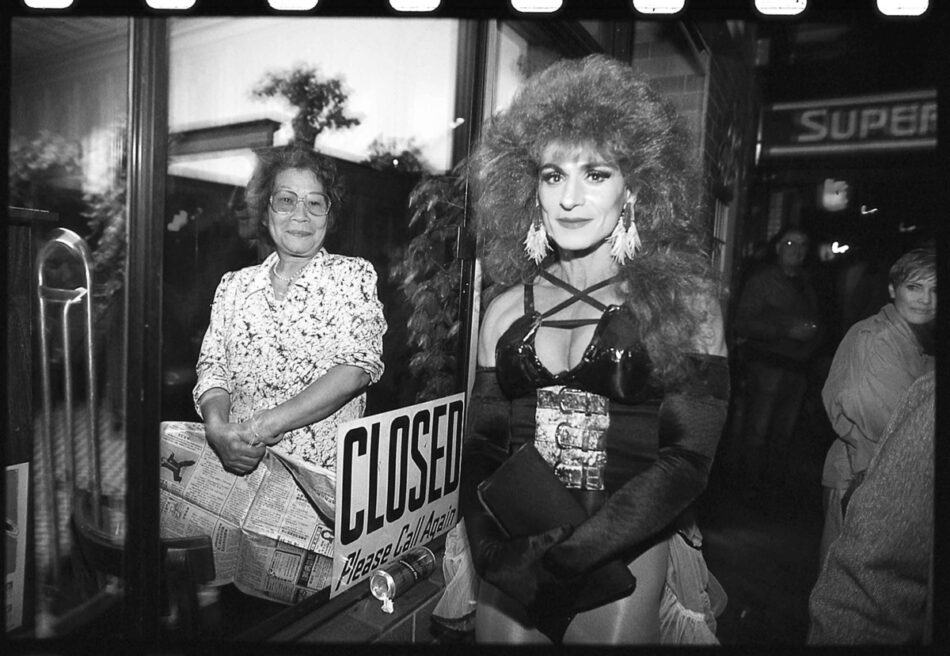

It was Halloween in San Francisco, and around the corner from my house a lone man in a grass skirt was juggling firesticks. Because he had put himself on display, we bantered freely with him, and as he replied he carried on nonchalantly with the flaming brands. We were still nearly ten blocks from the Castro, but people in costume were already appearing in ever-increasing numbers, and when we came down the last slope from Sixteenth Street we saw a solid mass of costumed bodies filling the intersection of Castro and Market and spreading up the street—a crowd of thousands. By day one of the busiest arteries in the city, Castro Street, the symbolic center of the city’s gay community, is often closed off for revelers. Or revelers and demonstrators, for here, more than anywhere else, the distinction between the two is blurred.

Notes on the Streets of San Francisco

Asserting a queer identity is something of a political act in itself. Asserting it festively subverts the long tradition of queers being furtive, marginal, and miserable—which makes hedonism, in its own peculiar way, revolutionary. Other streets here have their cultural life too: there’s the Mission, with its Latino communities and hipster invaders; the Haight, with its white slackers and deadheads; Folsom Street and the leather scene. Political protest has its own set of itineraries: from the Castro or from Dolores Park in the Mission or from Fifth and Market downtown to the Civic Center midway between all these points. What I’m most interested in here is how the mere act of occupying the streets as pedestrians is itself a significant political act. Whether the ostensible cause is peace and justice or trick-or-treat, the implicit cause is the importance of public space, of democratic encounters and unmediated communication—precisely what have traditionally made cities exciting political and cultural zones.

Halloween ‘97 in the Castro seemed particularly jubilant. Maybe this was because of the contrast with two years ago, when so many onlookers and fag-bashers showed up that the place seemed full of an audience in search of a circus. That year the drag queens made themselves scarce, hoping to avoid the loutish frat boys. But in ‘97 the city set up a decoy Halloween at the Civic Center, with an admission charge, live bands, beer for sale, and lots of security guards, leaving the Castro to the low-key and the local. And although many of the people who came to the street last October 31 were not gay, the crowd was harmonious: the majority were in costume and everyone was there to display and to mill. A century ago, displaying and milling were typical streetside activities. Local heiress and art patron Harriet Lane Levy wrote in her memoirs about promenading down Market Street (San Francisco’s main avenue) with her father every Saturday to look for friends and at strangers (and she writes, too, about the shocking thrill of straying off Market and venturing near one of the Barbary Coast brothels that were then, early in the century, so much a part of the city’s brutal festivity).1 In 1997 it was mostly the men who wore the high heels and the satin gowns. But the women held their own: one was dressed as Alice in Wonderland, another as Medusa, some as sci-fi creatures. I saw two separate revelers dressed as Tippi Hedren in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, with fake gulls attached to their blood-daubed early-1960s cocktail suits. I saw three teams of The Cat in the Hat, with Thing One and Thing Two. And then there were the gargoyle with spring-action wings and rust-tinted flesh, Two Gentlemen of Verona, the half dozen or so Pippi Longstockings (of both genders), some silver science-fiction teams, a crew guarding a dead Elvis in his coffin, the grouchy-looking older man with a cannon-like foam-rubber phallus, and the group of neat Asian guys in togas with ivy wreaths.

A lot of the people must have begun working on their costumes months ago, and the exhilaration of displaying and inspecting was contagious. One thing that made this particular gathering extraordinary was the lack of commerce: no comestibles were being sold, no T-shirts being hawked, no political literature being purveyed. There weren’t even AIDS organizations handing out condoms. There was only a satanic-looking figure who handed me a contract for my soul, written in exquisitely dull legal language that gave a hint as to his day job. But not only commerce was missing; another unusual thing that night was the lack of authority. There were no busy-looking organizers, no groups defining parameters—just a few police who lounged on their motorcycles by the barriers and kept out the cars. To put it another way: no outside forces shaped this event; it was a case of people reveling for the sake of revelry.

Having recently returned to San Francisco after some months in New Mexico—a place with virtually no urban public space—I was moved and thrilled by this amateur theater of the street and the freedom of its interchanges. This is what cities are supposed to offer, this unregulated exchange of glances, of ideas and possibilities, in the semi-anonymous space of street and crowd. Few cities offer that anymore—but somehow, in San Francisco, the streets remain a popular political and cultural arena.

When Joseph Beuys spoke about “everyone an artist,” he may have been thinking of people like himself, of people who were rigorous and avant-garde. This is a more likely scenario, and a more Californian one: everyone is an artist, but one’s masterpiece is one’s identity inscribed on the body and displayed proudly in public, whether it’s a leatherman whose cowhide clothes barely conceal his gym-generated muscle mass, or a slacker so covered in tattoos she looks like the Sunday funnies, or the various neo-tribals with their dreadlocks and baggies, or the bicyclist wearing a “One Less Car” T-shirt, or, for that matter, the street preachers holding their corner at Sixteenth and Mission or Fifth and Market (where a man with a “no unlawful sex” sandwich-board has been preaching his own peculiar gospel for more than a decade).

In a sense, to be out and about in the conglomeration of San Francisco neighborhoods near the Castro and Mission is also to be on the inside, inside a mutual understanding of culture, irony, and politics. This is the best aspect of living in San Francisco. And though it’s easy to ridicule a culture that seems to express itself in tattoos and lattés, it’s less easy to dismiss a place that has managed to maintain an open, street- and pedestrian-based culture that makes possible not only festivals but uprisings; and it’s important to remember that this sometimes solipsistic personal-is-political display is part of a continuum that encompasses an activist community genuinely concerned about peace, justice, and the lives of others. Which is to say that, despite its self-absorbed, white-middle-class center, a part of San Francisco has maintained something of the kind of democratic life that is vanishing elsewhere (and the Castro is, after all, where the White Night riots occurred; having built a community for pleasure, these gay men were able to use it to protest the farcical verdict in the “Twinkie defense” trial of Harvey Milk’s assassin Dan White; the event rivaled the local Rodney King uprisings in fierceness). This is the fragile, silly utopia people move to San Francisco for or make fun of from elsewhere. And though most of the subculturalists have their own communities, streets are an essential part of what makes San Francisco so appealing to this convergence of divergence.

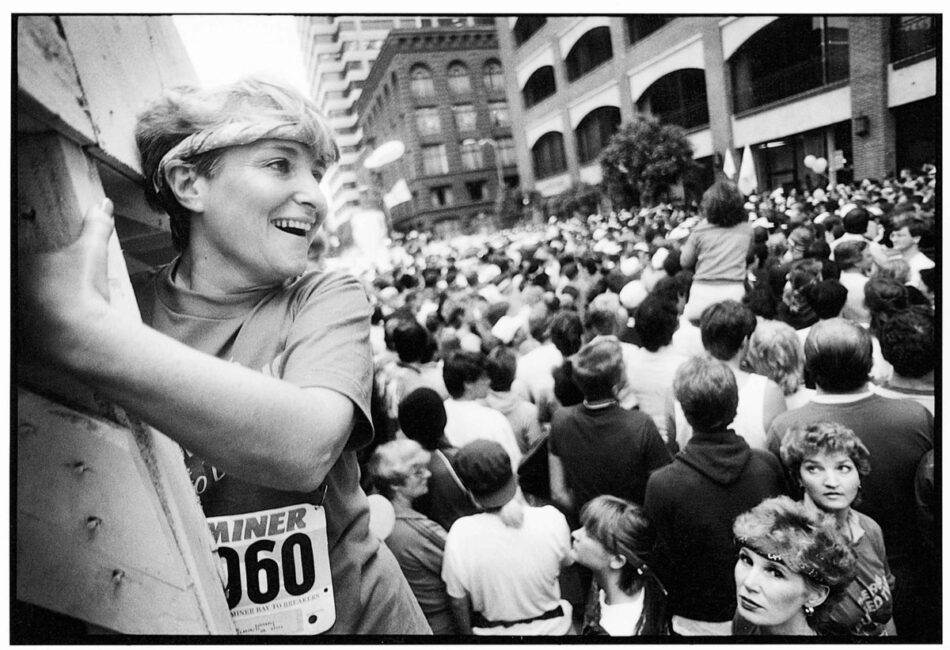

Streets, I hasten to add, as places in themselves rather than as mere traffic arteries, neutral conduits that link one place to another. San Francisco is often called the most European of American cities, but this comment is rarely explained. What I think it means is that San Francisco, in scale and street life, still embodies the powerful idea of the city as a place of unmediated encounters; in contrast, most other cities of the American West are merely enlarged suburbs, scrupulously controlled and segregated, designed for the non-interactions of motorists shuttling between private places rather than the interactions of pedestrians in public ones. So while San Francisco’s myriad cults of self-invention and self-exploration belong squarely to the American tradition of health nuts and utopian communities, their arena belongs to that continental tradition of boulevardiers, flaneurs, grisettes, and clochards. Wolfgang Schivelbusch, writing of the mid-19th-century “remodeling of Paris to allow for flowing traffic, with the construction of streets ‘which have no significance in themselves but are essentially means of connection,’” declares: “The streets that Haussmann created served only traffic, a fact that distinguished them from the medieval streets and lanes that they destroyed, whose function was not so much to serve traffic as to be a forum for neighborhood life; it also distinguished them from the boulevards and avenues of the Baroque, whose linearity and width was designed more for pomp and ceremony than for mere traffic.”2 When the spectrum of street actions is viewed as a whole, San Francisco does indeed seem like some mutated descendant of those older versions of the city, with its plethora of public festivities—of Carneval, Cinco de Mayo, the Bay to Breakers (a seven-mile cross-city run famous for its costumes and its crowds) in May, the Gay Pride Parade in June (the largest event of the year), the Tenderloin Street Theater Festival, September’s Folsom Street Fair (for S & M practitioners and voyeurs), the massive Halloween party in the Castro every year, and Dia de los Muertos in November in the Mission district. Add to all this the more conventional parades for Chinese New Year, and for St. Patrick’s, Columbus, and Veterans’ Days.

In The Architecture of Fear, Fred Dewey writes that “[t]he problem in Los Angeles, and increasingly elsewhere, is not simply that people do not participate, that they lack a civic sense. The problem is that the places necessary for people to participate, where people might appear to each other as political creatures, have been eliminated.”3 Los Angeles is often regarded as emblematic of the creepy future that awaits all cities; in this sense a place like San Francisco, in which the kind of spaces Dewey speaks of remain relatively intact, can be seen as embodying an urbanism of the past. But Los Angeles and the Bay Area do have one thing in common: they are ranked, respectively, first and second in traffic congestion nationwide. San Franciscans have the option of relinquishing their automobiles, given their city’s scale and existing and potential transit alternatives. They haven’t exercised this option, however, and instead ever angrier drivers speed ever more dangerously through the city in a collective rampage of impatience. So the right to the city’s public space is currently being fought over, insidiously by the rising number of vehicles barreling into or barely missing bicyclists and walkers, overtly in debates over the monthly Critical Mass bicycle ride (itself a street protest about the right of bicyclists to safety and equal access),4 and implicitly in the ongoing debates about whether the homeless have a right to inhabit sidewalks and parks. To some extent, these are debates about how to interpret the First Amendment, which lists the “right of the people peaceably to assemble,” along with freedom of the press and of religion, as essential rights. Challenges to freedom of speech and religion are easily recognized and fiercely fought; the elimination of the possibility of assembly, whether due to urban design or other factors, is harder to see and trace, and it is seldom framed as a civil rights issue.5 But the privatization of the public realm eliminates the possibility of unmediated political action—of the kind of uprisings and protests that have been a part of modern urban life at least since the storming of the Bastille in 1789.

When streets effectively belong to cars, they cease to function as places and become mere connectors between places; and the places they connect—homes, malls, offices, gyms, etc.—are likely to be highly controlled and segregated. The unexpected is largely imagined as the dangerous in modern cities, and so the elimination of the possibility of encounters between strangers is framed as an issue of safety. But to eliminate public spaces is, ultimately, to eliminate “the public.” The wholly private person is no longer a citizen, capable of experiencing and acting in common with fellow citizens, or of developing familiarity and even friendship with those people who are not presorted into his or her social subcategories. Citizenship is predicated on the notion that we have something in common with strangers, just as democracy is based upon trust in strangers. And although the street action of San Francisco largely involves subgroups of shared belief, the members of those societies in miniature do not necessarily know each other in private life. Using the space of the streets thereby serves to forge connections, as well as to demonstrate the strength and style of the group to the larger public that may be its audience, either as immediate spectators or as consumers of media reports on this march or that parade. For sheer quantity of direct-action politics and guerrilla protests, San Francisco probably leads the nation; and though we citizens like to congratulate ourselves on this as if it were entirely a matter of morale, I have long suspected that it is at least partly a matter of urban design and benign weather.

Two days after Halloween, I walked across town at dusk to the Mission, down the scuzzy bustle of the lower Haight and then down Fillmore Street toward Market Street, where I ran into David Bonetti, the art critic for the San Francisco Examiner. Something I said set him off, and he held forth marvelously on the charms of his native Boston, on Olmsted’s parks, on Boston’s friendliness to pedestrians, and on the way San Francisco’s hills, its geography beyond the core of the Haight, the Castro, and the Mission, doesn’t allow for the same kind of pedestrian life. But there we stood, at the point where those three neighborhoods meet each other in the no-man’s-land of mid-Market, and it was a good enough walking city for me, and on this night a sociable one. Halfway to my destination in the Mission I ran into another acquaintance, an artist unrecognizable for the black and white greasepaint that transformed his face into a skull. Finally I got to 24th Street, in the heart of this Latino district, which was sealed off by cops and portable barricades for celebration of Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead.

There were so many people packed in and around the intersection that the procession had trouble getting through—but there wasn’t, in any case, a very clear distinction between audience and parade. A lot of people waited to see friends go by and then lit their own candles and joined in. Dia de los Muertos is a major holiday in Mexico, born of the mingling of Catholicism with the festive attitude toward death of the country’s earlier cultures. Dia de los Muertos in San Francisco is a hybridized holiday, celebrated at the instigation of Latino arts groups but attended mostly by white aficionados. Ten years ago the crowd seemed dominated by punks, who thought the iconography of death was cool, but most of the people this year seemed to recognize the event as a remembrance of the recently deceased and promenaded with more tender, subdued jubilance. Someday Halloween and Dia de los Muertos may merge and evolve into a major three-day local holiday, like Mardi Gras in New Orleans or Carneval in Rio. The two holidays are already mixtures that emerge from the encounter of Christianity with other cultures—one with Celtic, the other with Aztec-Mayan. I suspect that any new festival will be about further transitions and transgressions—about the encounter of those festivals with the drag-queen, modern primitive, and other alternative cultures.

Like Halloween, this holiday had inspired a lot of fanciful decoration, from people with painted faces to the more elaborate mechanical skeletons and the flotilla of huge crosses adorned in complex tissue-paper cutouts. On the journey home, I ran into several homeless men sitting quietly, and one sleeping in a hammock strung between a utility pole and a tree. Almost home, I found myself walking the same way along Scott Street as a girl in fishnet stockings and a leopardskin swing coat, carrying a couple of shopping bags. I could see her hesitate as she heard my footsteps behind her on streets that, because no longer crowded, were no longer so safe. I said “It’s only a girl,” and she turned happily around and we struck up a friendly conversation. She was dressed up for a belated Halloween party, she said, and in a few weeks was moving back to Massachusetts, since she missed the seasons that David Bonetti told me were one aspect of Boston he could do without very happily.

Eight days later I was back in the streets—and I must say that there is something very satisfying about walking down the middle of a street that’s usually filled with cars. These formal gatherings compensate for the usual vulnerability of the lone pedestrian to crime and traffic. Whatever else they achieve, they are already victorious in having seized the streets. This time it was Market Street at midday, in the sporadic first rains of November, and the occasion was a demonstration to commemorate the second anniversary of the assassination of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni environmental and human rights activists in Nigeria on November 10, 1995, and to protest Shell Oil’s continued involvement in the repression and environmental devastation of that country. My brother and his partner were among the main organizers, so this protest was also a family visit and show of support. The demonstrators—mostly white countercultural types along with a few cheery-looking Nigerian exiles—were led by a huge, exuberant-faced puppet of Saro-Wiwa clad in African fabric, followed by other puppets, drummers, sign-carriers, and stilt-walkers, a protest worth looking at for office workers on their break. It was a legal demonstration, and the police parted the traffic and we marched down the middle of the street to Shell Corner, where the Shell Building stands at Battery and Bush, and where a little street-theater protest took place. The occasional driver honked and shouted in support. Perhaps a hundred people were there.

The Nigerians had told my brother a few days before that the city of Oakland’s decision to divest from Nigeria hadn’t even made the news here, but that it had made big headlines at home and that this demo too would no doubt be noted there. So we were out in public for the passersby on the streets of San Francisco, but also for the media public of Nigeria, for their government and an oil corporation on the other side of the world, as well as for the Nigerians who couldn’t protest at home. In this sense, the demonstration took place not only in the literal public space of San Francisco’s streets but also in the virtual public spaces of information bounced around the globe. (It’s not a coincidence that “media” and “mediate” have the same root; political action in real public space may be the only way to engage in direct, unmediated communication with strangers, but it’s also a way to reach the media by literally making news.) The protest felt surprisingly like the street celebrations for Halloween and Dia de los Muertos, not only because, as demonstrations go, it was quite festive, but also because it was about occupying the street for communication and community rather than for transportation. It was about engagement with public ideas rather than with the private production and consumption that overwhelm most modern lives. And it was about articulating a common purpose in public, communicating that purpose to passersby, and most of all, making use of civic space to act as citizens—to engage in political and cultural dialogue with each other and with strangers.

San Francisco has ideal public spaces for public activity (although its federal building looks like the black obelisk in 2001: A Space Odyssey), but the right to use them is often squelched. San Francisco has a local ordinance whereby “obstructing a public thoroughfare” is a misdemeanor. Created as a measure for arresting streetwalkers, it has since been used to arrest homeless people and, most outrageously, activists. On many occasions, hundreds or thousands of protesters have been arrested, often without the legally required order to disperse being given first. Like many harassment laws, this one seldom holds up in court, even as it allows the police to continue removing people from public spaces in violation of their First Amendment rights. Another charge, invoked most recently in the July Critical Mass ride, was “illegal assembly.” At stake is whether the daily uses of public space in service of production and consumption should take precedence over the occasional uses for citizenship and celebration.

Rebecca Solnit is a writer who lives in San Francisco. She is the author of several books, including, most recently, A Book of Migrations: Some Passages in Ireland (Verso, 1997).